This is where I’m starting—a depopulated village on Loch Fyne, which is one of the west coast’s many “sea lochs,” long arms of the Atlantic Ocean that invade the mainland like fjords. It took a little over three hours to get here from Glasgow by bus.

As with all places of habitation in Scotland no matter the size, Ardrishaig is rich in history, and especially the history of the country’s diaspora. Which we’ll get into, of course.

But first, here are a few statistics about this year’s Great Outdoors Challenge, thoughtfully compiled by Sue Oxley and Ali Ogden, the event’s indefatigable coordinators.

There are 379 walkers from 16 countries. The vast majority are from the United Kingdom, but there are also 29 from the United States, 21 from the Netherlands, seven from Denmark, six from Canada, five from Germany, and one each from Austria, Barbados, Belgium, Finland, France, Ireland, Poland, Sweden, Uganda—and the first person ever from Japan.

The youngest walker is an 18-year-old man from Oregon. The oldest are a couple, the Borwits of Laurel, Maryland, whose combined age is 176. The median age looks to be about 60.

One person is making his 29th crossing, and another his 28th. (This is the 40th year of the event). 103 people are doing it for the first time. 77 people are leaving from the most popular starting point, a place called Shiel Bridge. Only five are leaving from Ardrishaig.

Which gets us back to the subject at hand.

The village is a couple of streets clinging longitudinally to the western shore of Loch Fyne. It has two hotels (only one of which—mine, luckily—serves dinner), two convenience stores, a “hair-and-health” salon, a bar that appears to be closed, a flower shop, a second-hand store, a Jehovah’s Witnesses Kingdom Hall, and lots of places for rent or sale.

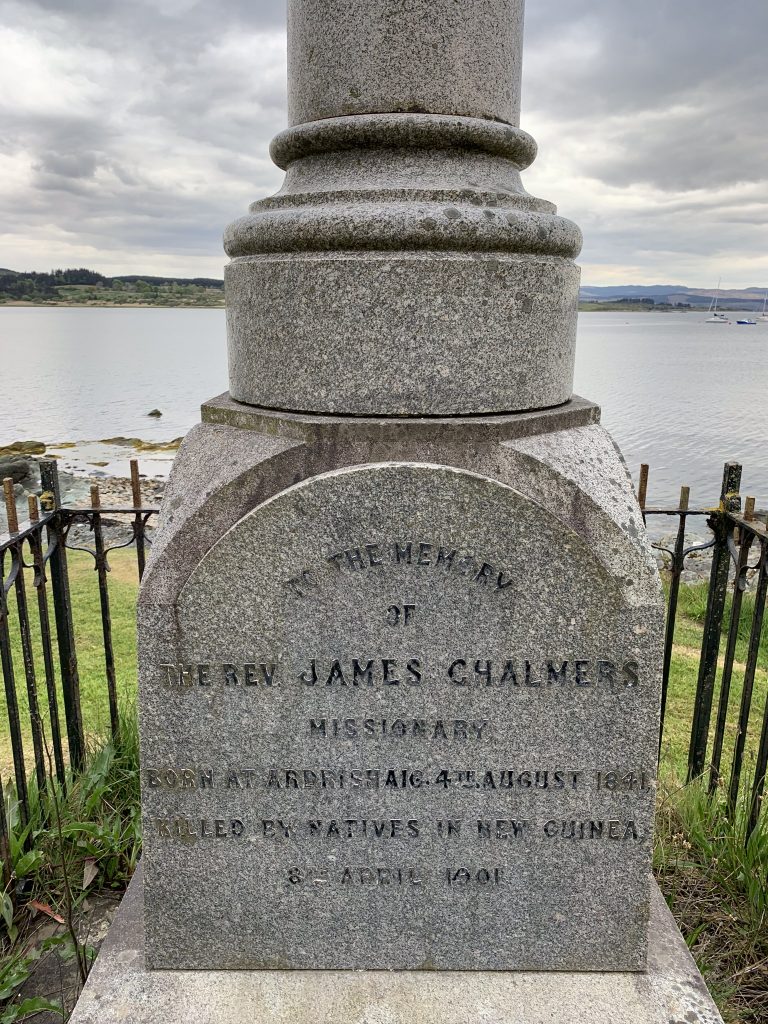

Directly across from the hotel, next to the loch, is a small memorial to James Chalmers, a missionary and son of Ardrishaig who was killed by natives in New Guinea in 1901–a member of the diaspora who didn’t fare well.

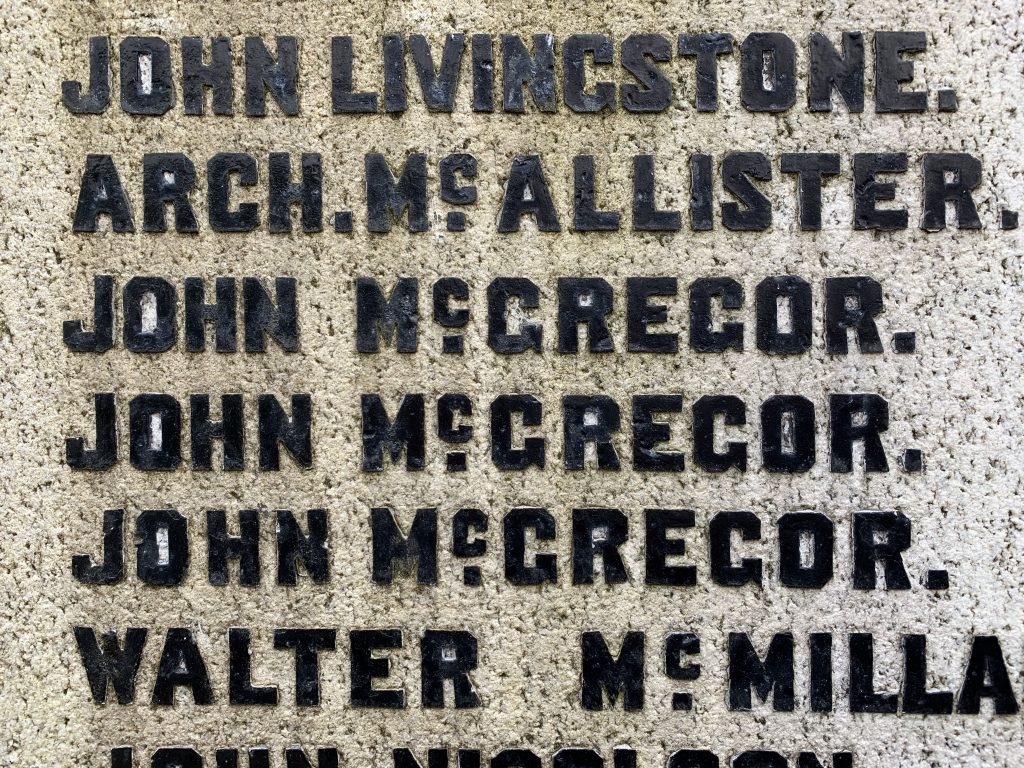

Farther down the road is a cenotaph to the dead of the Great War, which every Scottish village has because none was untouched by that conflagration. Forty names are listed, the officers named first—a protocol abandoned in late-constructed monuments because of complaints from veterans.

The names include three John McGregors, and two Grahams (Hugh and Colin), who served in the New Zealand forces. Perhaps they were brothers who’d emigrated together.

The monument gazes at the loch, as the men it memorializes did.

There was still a little activity to be viewed, even after 5 o’clock. I wandered down to the shore and found a 47-year-old fisherman named David Russell (camera-shy), who was power-washing his langoustine traps.

The langoustines are off shedding and hiding for a month, so this is the time to pull the traps, scrape off the barnacles and slime, and make them look good (which they do).

This is a year-round fishery. Russell runs about 1,000 traps, which seemed like a lot to me, although he said some operations have more than 4,000. They’re fished once every three days. The bait is hard-salted herring. Rotten or soft bait isn’t used because the crabs take it all. Ten in a trap is a very good haul. The average size of his keepers is 100 grams (although frankly that didn’t give me much of an idea of size).

The shellfish are sold live, exclusively to Spain, he said. You mean I can’t buy a dinner of langoustines here? I asked.

“Not here you can’t,” he said. “But when people from Scotland go to Spain, it’s the first thing they order.”

David Russell is Ardishraig’s only fisherman. He said there used to be a big herring fleet here, but that fishery collapsed a half-century or more ago.

“In the harbor you could walk on boats all the way to the lighthouse,” he said, pointing to a sea wall behind him. When I walked over and looked, there was one forlorn motorboat and five unused mooring balls.

A canal enters Loch Fyne in Ardrishaig. It looks to be still operating, although too small for modern shipping. I’m walking up it for part of today, so I may soon know more.

The Crinan Canal

Several sailboats were berthed in a basin near the first lock. Some were a few weekends short of presentable, but one was a showpiece. I admired it with an okay sign, and the owner, Jackie Kay, stepped out of the cabin to greet me.

We talked for a bit and then, as it was cold, he invited me inside.

Mr. Kay is 80, a widower. He runs a small boatyard in town that specializes in refurbishing “classic boats”—wooden vessels from yesteryear. Among his accomplishments are two 26-foot steam launches, now plying the River Thames in private hands. He also builds small wooden boats, mostly dinghies.

He built his boat himself. It took seven years. He’s lived on it since his wife died, although he lived ashore in his house last winter and had the boat under cover, so he could get all the varnishing done at once. I told him I’m always amazed when I see a wooden boat with spotless bright work.

“I keep on top of everything. That way it’s easy,” he said, although I was not entirely convinced.

The boat’s name, Juliet Kilo, is the letter-naming protocol for “J” and “K,” his initials. In the summer he takes it out for a sail “about once a fortnight,” he said. He has three children, two of whom like to sail. I told him he was kind to interrupt his reading to invite a stranger aboard.

“Well, it’s always nice to hear a compliment on the boat,” he said.

He’s still working, and I told him I might stop by his boatyard tomorrow to see it. He said that’d be fine. But it won’t happen, I’m afraid.

It’s time to walk.

Lovely beginning to your walk. Let’s make a date to go to the Walters in October. (Do we have to walk there?)