I got the idea to walk this route when I learned that parts of the Moray Coast had been used to practice amphibious landings in World War II in advance of the Normandy invasion.

It turns out very little has been written on this subject. Winston Churchill devoted two sentences to it in his six-volume history of World War II.

“One British division with its naval counterpart did all its earlier training in the Moray Firth area of Scotland. The winter storms prepared them for the rough-and-tumble of D-Day.”

Information from various sources, however, reveals that exercises occurred from December 1943 to March 1944. They involved principally the 3rd Infantry Division of the British Army, as well as Navy and RAF forces.

These “combined operations” we’re unusual and unpredictable, given the different command structures and cultures of the military services. People paid with their lives getting the kinks worked out (as a later post will describe).

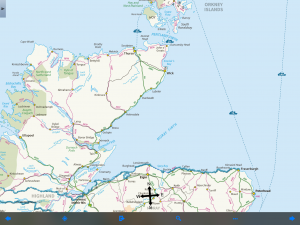

Some sources say the two shores of the Moray Firth were chosen because they resemble the beaches of Normandy where the invasion of France was to take place. How true that is I don’t know. I’ve never been to Normandy. I know, however, that the beaches I walked on where the rehearsals occurred do not have high bluffs over them, as I’ve seen in some photographs of the Normandy beaches.

What this area clearly offered, then and now, are long beaches (several over five miles); tides that leave huge expanses of sand when the water is out; cold, rough water; and relatively few people.

On November 11, 1943, the village of Inver on the Tarbat Peninsula that forms the north shore of the Moray Firth was told it had one month to finish the harvests and move all inhabitants and animals. The affected area was 15 square miles and had about 900 residents. There were 56 children in the Inver primary school, which closed November 26.

A “displenishing sale” was held at the nearby town of Dingwall, where 1,050 cattle, 8,000 sheep, 60 horses, and 50 pigs were sold. (Chickens weren’t sold; they were taken or eaten before the evacuation). The prices were low because of the season and a prohibition against widespread advertising of the sale for reasons of war security.

Tarbat was a the site for live-fire with tank weapons, as well as a limited amount of shelling from ships.

About the same time, a sparsely populated area just west of the mouth of the River Findhorn, including a hamlet named Kintessack, was given by three weeks to evacuate. Eighteen Italian prisoners of war were brought in to help with the threshing of grain and the digging of potatoes and sugar beets.

Personal accounts of the exercises are rare.

A 2007 doctoral dissertation by historian Tracy Craggs (University of Sheffield) quotes a veteran named Peter Brown, who recalled a mock assault in November 1943. He was immersed after jumping out of the landing craft.

” ‘Our objective in this exercise was a wood about fifteen miles inland across rough countryside. By the time we got there and had dug a slit trench I was in a pretty poor state. My clothes had partially dried but as darkness fell and it got colder I could not stop shivering and began to think I would not last the night. However about three in the morning the exercise was called off and we were able to light a huge bonfire and this, together with a generous rum ration, probably saved my life’. ”

(I personally doubt the beach assault was followed by a 15-mile walk inland. Fifteen-hundred yards is more likely. But who knows?)

The historian writes that “in January, three days were spent at Burghead Bay during Exercise `Grab’, with the intention `to practice assaults on beaches and the capture of initial objectives by assault battalions’. There was also emphasis on night operations, including breaching minefields, compass work and direction finding, as well as time spent on the range.”

It was a difficult time of year to undertake such maneuvers, with winter seas and only six hours of daylight. It’s intimidating enough now, when the weather is pretty good and there’s useful light for about 19 hours a day.

Exercises at Burghead on December 22 and January 9 had landing craft leave from Fort George, cross the firth, and return to the southern shore to simulate a crossing of the English Channel. There was apparently much seasickness.

The biggest exercise was on March 30-31, also at Burghead, where 204 Sherman tanks, 32 Stuart tanks, and all the infantry of the 3d Division, plus cruisers and destroyers, took part, according to the pamphlet “Evacuation: Tarbat Peninsula 1943-4” (undated) by Dr. James A. Fallon.

There were surprisingly few casualties. One occurred in February and involved so-called “duplex-drive” tanks, which were outfitted with watertight collars that allowed them to float and move with a propeller connected to the engine. Two tanks swamped and one person drowned. In all, five tanks were lost in the rehearsals, according to records.

In April, the troops moved to the south coast of England, where larger, more complicated, and in one case disastrous, rehearsals were held involving American and Canadian forces as well as British.

In May, the local people were allowed to return to Inver. The government paid for damages to houses and farm buildings. In many places, however, the ground had been compacted from tanks and took years to recover. Purebred herds that had taken decades to build were gone. Farmers removed unexploded shells from the ground for a long time, according to a pamphlet “The Evacuation of Inver” put together by the village’s schoolchildren a number of years ago.

It was all chocked up to “doing your bit” for the war effort.

There were other, subtle disruptions, too. The Inver school reopened at the end of August, and the logbook for September 1, 1944 notes: “Attendance is disappointing. Some of the boys absent themselves from School for no apparent reason.”

A newspaper account sent to me by Tim Negus, one of the volunteers at the Findhorn Heritage Center, whom I met when I passed by, included this observation from a woman who was a schoolteacher when the area near the Findhorn was evacuated.

“All stoppers from the sinks were removed. I understand that the troops carried their own personal stoppers wherever they went. But I hasten to add the soldiers took the stoppers only.”

A number of years ago, Tim tried hard to find someone who remembered the assaults. They would have been visible from the village of Findhorn, which was not evacuated.

“It must have been like a hundred Guy Fawkes Days,” he said. But he could find nobody who recalled seeing them.

It turns out a plaque on the beachfront at Nairn may tell the whole story.

Silent we came

Silent we left

To strike a blow for freedom

Recent Comments