After two nights at Bradley Point one option was to stay a third night if the conditions were too trying to head off. Such a strategy would have made the following days longer and removed all future flexibility in the schedule. The group decided to move on, with the understanding that if the going was too rough we would turn around and come back to the campsite.

We paddled westward for several miles in the inlet between Wassaw and Ossabaw islands. Both wind and current were in our faces, which made for a tiring and choppy, but not especially tricky, morning. Eventually we got to the entrance of the north-south creek through Ossabaw Island, and entered it.

On an incoming tide, water flows into such creeks from both the southern and the northern ends. As a consequence, there’s a place somewhere near the middle of the island where the two fronts of rising water meet–“the dividing.” On this day, Don kept us going until we got to the dividing so we could take full advantage of the tidal assist.

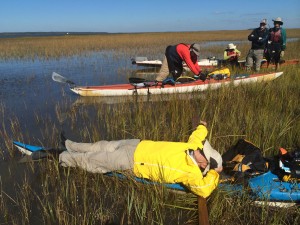

We were quite tired when we got to that estimated place and finally took a break. There was no high ground, only a Juncus marsh in ankle-deep in water.

Some people found ingenious ways to rest.

Our desire on the trip was to live at least partly off the fat of the land–which is to say off our, or somebody else’s. fishing. Don and Eric Schwaab fished often and caught nothing, and the few other anglers we saw were similarly unlucky. We saw some shrimp boats far off, but failed to get their attention. However, we did run into a crabber farther down this creek. We bought $35 worth of blue crabs, all of which, he told us, were bound for Maryland, where the demand was higher and the supply smaller than here.

Without going ashore (but with help), Don managed to empty his back storage hold for the crabs. After landing at the camping spot, at the southern end of Ossabaw on Jacobs Creek, we off-loaded them.

We swam in the creek, as did a dolphin, its dorsal fin appearing periodically as it herded fish into the bank. (You can see it in the distance on the left).

The next day the conditions were finally right to go outside. We crossed yet another inlet, this time in perfectly calm water, and started down St. Catherines Island. It was thrilling to be in the ocean.

We came ashore at a mid-island creek–McQueen Inlet–through breaking swells, an exciting ride. The initial choice of a campsite was abandoned because we thought it might have bugs when the wind fell off in the evening. Instead, we crossed the inlet to a dogleg of beach, where there was a perfect place.

A buoy had washed ashore, evidence of how rough the weather could get.

I went swimming.

Bob cut trivets–mementoes of the trip–out of a piece of cedar that was so red it appeared to bleed on the sand.

We had plenty of room.

Don had along with him in a watertight Pelican case a library of books on the region’s natural and human history. It contained a copy of the secret journal that Frances Anne Kemble, an English actress, kept from her sojourn on plantations on Butler and St. Simons islands in the winter of 1838-39.

Known as “Fanny,” Kemble in 1834 married a Philadelphian named Pierce Mease Butler, who inherited three plantations in South Carolina and Georgia early in their marriage. Kemble was an abolitionist and hoped to convince her husband to free his slaves on a visit they made to the holdings. She was appalled by the working conditions, punishment, housing and sexual exploitation she saw, recording her findings in a journal that wasn’t published until 1863, long after she and Butler divorced.

Butler didn’t free his slaves. But threatened with bankruptcy, he sold about 450 of them in 1859. The event was so large that The New York Tribune covered it. Its correspondent wrote: “The buyers were generally of a rough breed, slangy, profane and bearish, being for the most part from the back river and swamp plantations, where the elegancies of polite life are not, perhaps, developed to their fullest extent. In fact, the humanities are sadly neglected by the petty tyrants of the rice-fields . . . comprehending only revolvers and kindred delicacies.”

I read three excerpts from the journal–her writing is clear, detailed and unflowery for its time–as we tried to imagine what had gone on almost beneath our feet and fire.

Recent Comments