The end of The Great Outdoors Challenge is always something of a bring-down. The emptiness, the brown and gray, the mysteries real and imagined, give way to the modern world.

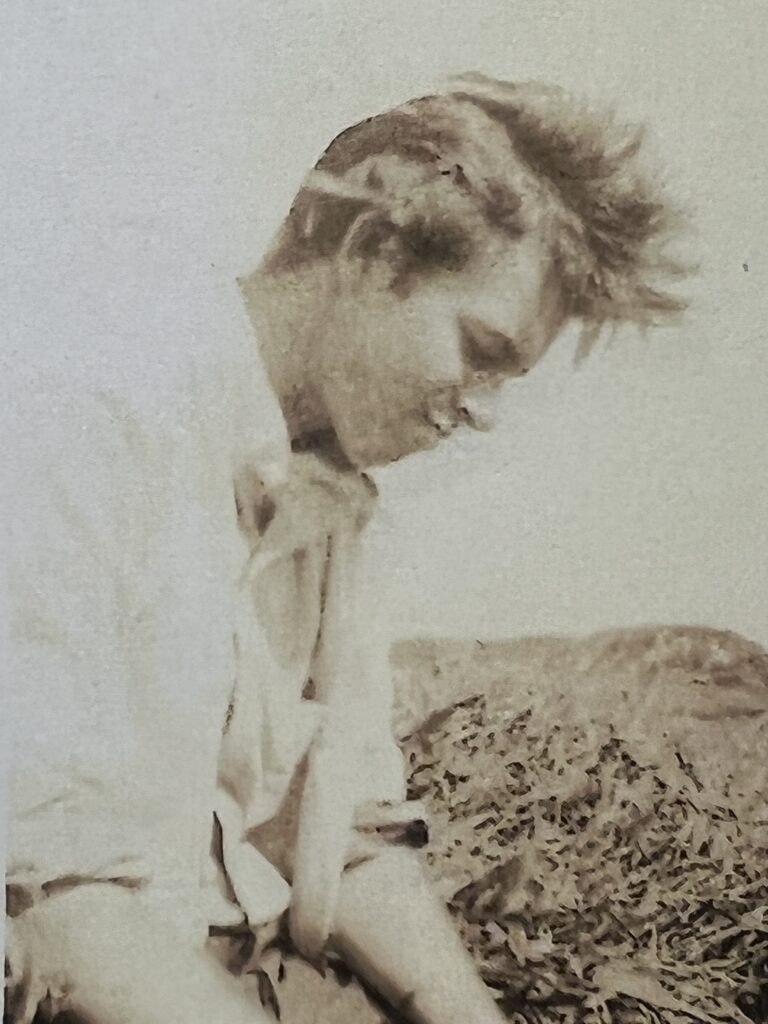

You leave behind scenes like this, which looks like Homer in the Adirondacks

and enter bright-colored farmland worthy of Van Gogh.

It’s still grazing country. That’s a herd of sheep on the path ahead.

There are interesting things to see, of course. We walked by Invermark Castle, built in 1526 on a site where a castle existed back to the 1300s. It’s wonderfully intact. The other side has a semi-circular corner tower lacking only Rapunzel.

One of the things that makes this reentry tolerable is the promise of meeting a mass of Challengers at Tarfside, a village that hosts a Scots version of a mountain-man rendezvous.

People set up tents on the village green—sometimes there are 40–and eat sandwiches and cake at the local church hall made by volunteers, most of them Challenge alumni and alumnae. Afterward, everyone repairs to the clubhouse of a fraternal organization, where the beer taps open for a price and walkers exchange exaggerated accounts of the previous week.

Alas, there was none of that this time. I’m a little unclear why not.

Covid is the standing excuse for any buzzkill decision, but I’ve also heard there were complaints of objectionable behavior from bibulous Challengers in previous years. By now you have a sense of this crowd. How much damage could a bunch of self-punishing 70-year-old bald men do? Maybe it was the women, and the sub-40 cohort.

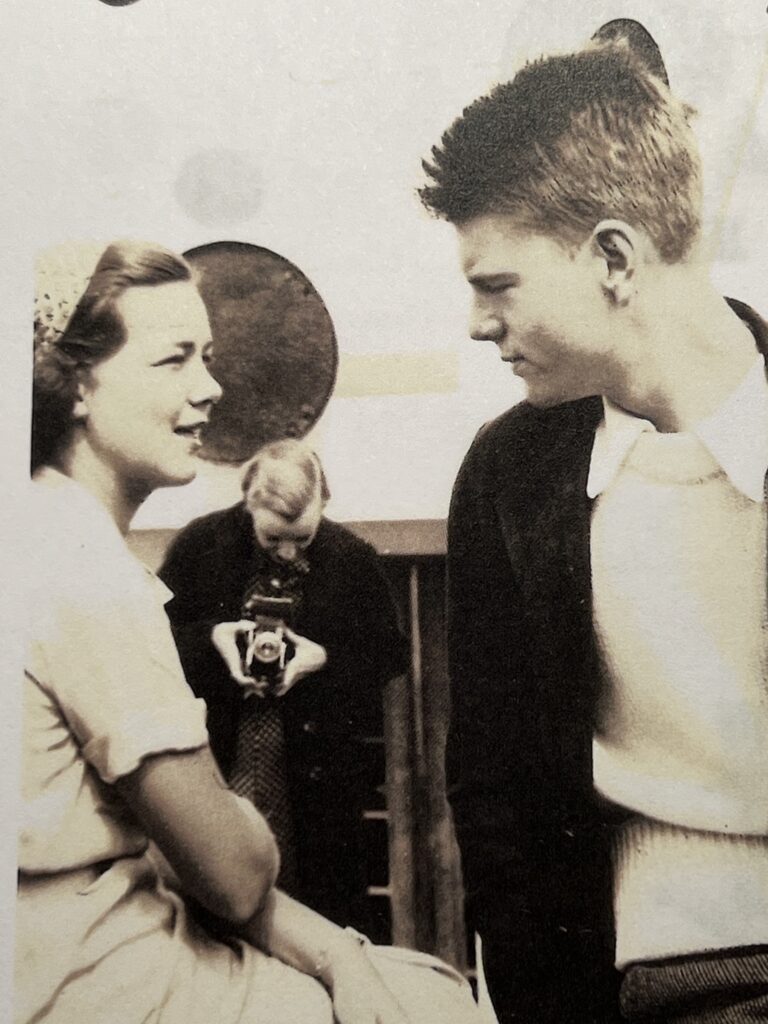

In any case, we drowned our sorrows in tea and nut bread at St. Drostans parish hall. One of the volunteers, Ann Thorn, was there in 2014 when I met my distant cousin, Marion Mitchell, who like me is descended from John Brown the Covenanter.

He was a Presbyterian martyr shot in cold blood on May 1, 1685, by a notorious English military enforcer, John Graham of Claverhouse, in front of his pregnant wife and two children. (There’s an obelisk to him on a Lowland moor my parents once visited.) His widow and her children moved to Ireland, and two sons moved from there to Pennsylvania in 1720.

The church offered 12 rooms for 25 pounds apiece (and toilets and showers, of course.) It tells you something about this group that I was the only Challenger in the place that night. My excuse: an underperforming tent. The real reason: I needed a place to write, and I wanted to sleep in a bed.

Personally, I hope superannuated dissipation returns to Tarfside someday.

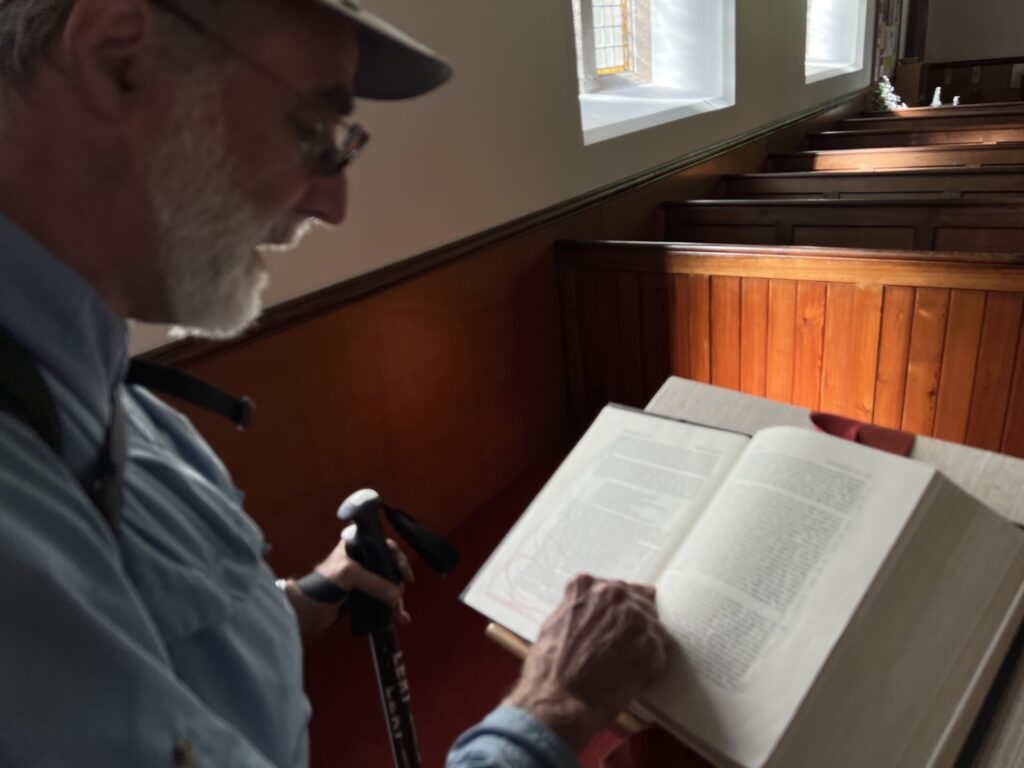

In its stead—and a good, if sober, substitute—was The Right Reverend Mark M. Beckwith’s reading (and later, on the road, interpretating) the Oak of Mamre story in Genesis 18, in which three angels tell Abraham that his wife Sarah will bear a child in old age.

St. Drostans (part of the Episcopal Church of Scotland) had in its nave a copy of a famous icon of this encounter, which, among other things, is about hospitality. Mark had contemplated it for an hour alone before Ole and I got up.

After Tarfside, we spent the night in Edzell, at the Panmure Arms Hotel. The original plan was to camp somewhere, perhaps sneaking onto the grounds of the ruins of Edzell Castle. By then, however, we were no longer casting around for good excuses for eating in a bar and sleeping in a bed.

The last day was 14 miles on road. The last climb was up the Hill of Morphie, which I’d done on a previous crossing. (Love that name.)

At its foot we met Rich, who like his wife, is a local school teacher. They’re used to seeing Challengers trudge by their house. He came out to greet us.

We talked for a few minutes. “We can’t get away this time of year,” he said enviously. But he and his wife have plans for the summer.

Coming down the hill I passed a road sign.

You’d think this was the end of the story, but it wasn’t quite. We still had to get to St. Cyrus, just ahead, and beyond it, in the mist, to the North Sea.

We got to the cliffs and looked out. It was a beautiful sight. We’d made it.

According to the built-in Health app on my phone, We’d walked 230 miles in 13 days. That included everything–walking around campsites and villages–not just time underway. And I think the app exaggerates distance. Nevertheless, it was a long way.

We still had ahead of us the podiatric intinction. We left our packs at the top of the bluff and walked down to the beach, Ole first. It was almost a half-mile.

We took off our boots and walked into the sea, and took a picture of ourselves.

We had to wait more than an hour for a bus to Montrose; luckily there was a pub nearby. When we arrived we signed in at Challenge Control, a room in the Park Hotel. Then we truly were done.

Sue Oxley, one half of the sainted “Ali and Sue” who run the show and have been communicating with us since last October, was there. She provided a few statistics.

So far, 74 people had “retired”—dropped out—from the starting field of 400. Because of the staggered starts that number could increase; there were still several days to go. That’s both more people, and a higher percentage, quitting than since 2015, and possibly longer.

The weather, and its associated hazards and discouragements, were the main reasons. Mountain Rescue had been called for three people, although one search was aborted when the person appeared.

I put my tent (slept in three nights) in front of the message board and taped to it a note saying it was for the taking–as long as the taker gave a donation to The Great Outdoors Challenge. I’ll be interested to get follow-up on that sometime.

The next morning I went into Challenge Control. The only person there was Pierre De Greef, the Belgian we’d briefly encountered when he came in late at the pony shed.

We talked for a while. As we exchanged observations, I realized he embodied the Challenger ethos in an extreme form. Everyone who does this has a bit of Pierre in him or her.

He’s 50. He has a sister, six years younger, who is schizophrenic. He dislikes it when people paper over her illness with euphemisms. (I don’t know the French ones.) In his walk he’s raising money for Macaulay College, a “community interest company” on the Hebridean Island of Lewis, where he lives. People with mental and social problems run a farm. Things are expected of them, and their work is productive. This is what he wants to support.

So far, he’d raised 1460 pounds of a target of 3750. The effort has liberated him, he said.

“For my sister, there is no escape. This has allowed me to speak freely of that.”

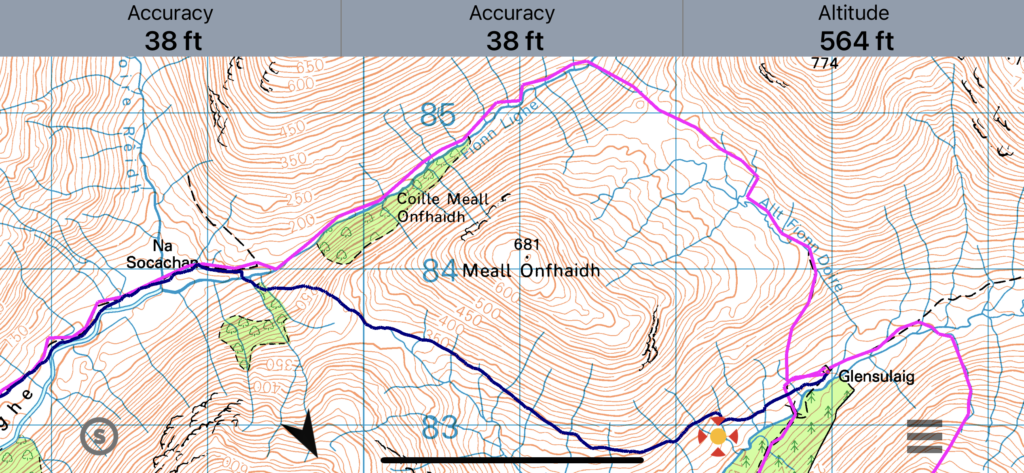

In his driven state he’d climbed 20 Munros—mountains over 3,000 feet—in 10 days. He’d walked 240 miles in 13 days. He pulled up his shirt. “I have lost eight kilograms,” he said, in amazement. (That’s 18 pounds.)

We’re all a little driven and we all have some agenda, however secret.

What it is for most Challengers was the topic of discussion in a tea break with some of the old English and Scottish guys one day about mid-crossing.

The consensus was that the illusion of keeping death at bay—“Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” as Dylan Thomas put it—was the main driver. I observed that when people are young, strength, speed, and perseverance allow them to accomplish feats of endurance. Perseverance is a lagging indicator of age and the last of the three to disappear. It’s what most of us were running on.

So how was this TGOC for me?

The route was harder, with lots more pathless walking. The weather was only a little worse—but at the beginning, when everything is difficult.

It was interesting to have a walking partner. I learned a lot from Mark Beckwith, and enjoyed getting to know him better. And Ole Hollesen—he was the Danish lagniappe.

I thank them both.

As for me, who knows if I’ll do this again? It was difficult, and my feet hurt a lot. I’m getting older and I’d rather not end with an incomplete crossing. If I never do it again, I will carry it with me.

In my cap I now have one more pin, or “badge,” as they call it over here. The coordinators promise they’ll send me a 2015 badge to replace the one I lost.

I consider myself in the deaccessioning stage of life. But this is a piece of bling I’ll happily and gratefully accept.

Recent Comments