One of the many advantages of this trip is that it contains no rapids of any size–a thoughtful accommodation by the Gods of Outdoor Recreation that comes to an abrupt end 2.5 miles below the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers.

What a traveler then encounters was described by Major Powell when he and one of his men, George Bradley, climbed partway up the canyon wall on July 19, 1869. (Back then the Colorado above the Confluence was called the Grand River.)

“What a world of grandeur is spread before us!” Powell wrote. “Below is the canyon through which the Colorado runs. We can trace its course for miles, and at points catch glimpses of the river. From the northwest comes the Green in a narrow winding gorge. From the northeast comes the Grand, through a canyon that seems bottomless from where we stand.”

The party explored and took geographical measurements for a few days before moving on. They soon learned what they were in for. Powell’s entry for July 23 begins: “On starting, we come at once to difficult rapids and falls, that in many places are more abrupt than in any of the canyons through which we have passed, and we decide to name this Cataract Canyon.”

Today, it’s well marked, and you have to sign in before you enter.

Our last campsite was at Spanish Bottom, on the right bank about three miles below the Confluence. We arrived at mid-morning, and after setting up had the rest of the day to do our own exploring.

We were at one end of The Maze, the remotest part of Canyonlands National Park. It is a place of confusing beauty and danger, a dozen sites of rock art, and almost no water. A permit is required to camp there, and fewer than 2,000 people do each year. Most go for a week

Our destinations were a geological formation called the Doll House and an Indian granary near it, far above the river. The “Doll House” is a curious name, as there’s no house and the stone spires are only vaguely doll-like (kachinas being the closest in appearance). Some indigenous groups called them “the Guards” and some settlers called them “the Soldiers”–both of which are more like it.

To get there we crossed a flat, scrubby area incised with dry creek beds–an ancient sandbar that was now a permanent plateau. The canyon wall and its flying buttresses of broken rock would not be an easy climb.

The ascent took 1 hour and 45 minutes. The day was hot and we stopped a few times; we also found a shady stretch in which to have lunch. In a few places someone had set or carved the stones into steps. I’m always touched by such hard and silent service for people the laborer will never meet.

This is the view down from about half way to the top. Our camp is around the corner where the river disappears in the upper left. The ascent was 1,100 feet in all.

The views from the top were worth every bit of effort. The revelation (although any glance at a map makes it obvious) is that the cliffs we’d been paddling along weren’t hiding plains or other unspectacular features behind their tops. Instead, there were numberless other canyons and cliffs, some more spectacular than the ones we’d seen.

As the Haitian proverb says, “Beyond mountains there are mountains.”

We didn’t have time or energy to explore the dolls of the Doll House, a half-day project at least.

Instead, we walked on to the granary.

On our way we encountered patches of ground that seemed to be covered with dead and mangy plant life. It was “biological soil crust”–a community of lichens, mosses, microfungi, and blue-green algae. Also known as cyanobacteria, the algae is among Earth’s oldest organisms, and was responsible for converting the original carbon-dioxide rich atmosphere into an oxygen-rich one.

This is what a National Park Service publication says about this groundcover.

In biological soil crust, cyanobacteria are dormant when dry. When wet, they move through the soil, leaving behind sticky fibers that form an intricate web. These fibers join soil particles together, creating a thick layer of soil [that acts] like a sponge, absorbing and storing water. Over time, lichen, moss, and other organisms grow onto the soil as well . . . Some crusts can be thousands of years old!

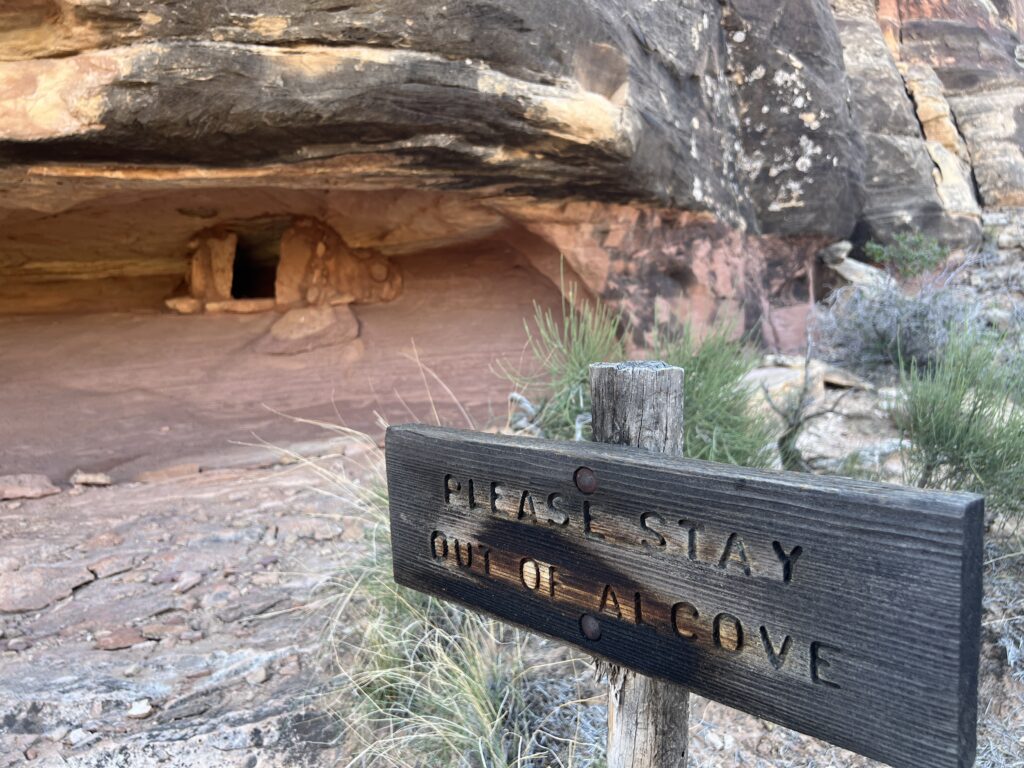

We eventually got to the granary. It’s four mud-walled compartments under a deep overhang. Three are on the left, one on the right.

These structures were well-built and undefiled, and with their mouth-like openings seemed to be speaking to us through time. It’s worth taking a minute to learn about the people who made them.

They were the the Mesa Verde Anasazi, of the Pueblo III period (AD 1150-1300), who arrived here after AD 1170. They were dry-land farmers who raised corn and squash, and occasionally cotton.

(What follows is from a 2021 publication entitled “Archaic Foragers and Ancestral Puebloans of Canyonlands National Park” by Alan R. Shroedl and Nancy J. Coulam.) https://npshistory.com/publications/cany/cap-5.pdf

Because of the marginal farm land in the park, it is hypothesized that at least some of the isolated granaries in the Maze and Island in the Sky districts are associated with fields planted in localities distant from habitation sites.

The additional storage features at these site may not reflect excess surpluses but rather a need to mitigate against potential crop shortages in the future . . . In the mid-AD 1200s, paleoenvironmental conditions for corn agriculture worsened and households increased the number of storage facilities while reducing the amount of living room space . . . Such a storage strategy would ensure having enough seed corn to replant fields after a year of losses and also to maintain an adequate food supply until the next productive farming season.

Canyonlands National Park was depopulated by AD 1300 . . . Archeologists once thought the “Great Drought” of AD 1275–1300 caused the Mesa Verde people to abandon the region, but this drought was not as severe as that of the mid-1100s . . . It now appears that these paleoclimatic factors combined with widespread violence may have been what led people to emigrate from the park and the region.

The place was without a visible gouge of graffiti, not even from centuries ago. I chose to view this as not just good behavior, but also homage to all that it took for people to live in this environment 900 years ago.

We descended as the air was finally starting to cool. It took 1 hour and 22 minutes, faster than the walk up, but still hard on tired legs. It was a good way to end the trip.

In the morning the outfitter picked us up, and lots of other people, in a jetboat and took us up the Colorado River–Powell’s “Grand”–to a paved put-in where a van waited.

It was time to go home.

Recent Comments