In March 2024, my friend Larry Abramson and I learned that we had once again not won in the lottery to get a permit to paddle on the Smith River in Montana. Instead of just hoping for better luck next year, we decided to take a trip on a river where it was still possible to get a permit for the season ahead–the Green River in southeastern Utah.

In the early 1980s I’d taken raft trips through two of the Green’s white-water canyons–Desolation and Gray. We chose a stretch through two canyons–Labyrinth and Stillwater–where there was no white water. Larry did the planning and rounded up eight interested people. We’d take canoes and go in early October, when the weather was cooler and the bugs, we hoped, would be gone.

Over the ensuing months people dropped out by ones and twos until it was only Larry and me.

He picked me up at the airport in Salt Lake City on the last day of September. Our destination was Helper, a town 116 miles to the south. We’d spend a night there and then go on to Moab, where we’d spend another night before rendezvousing with the outfitter who’d take us to our put-in on the Green River.

Helper seemed like the right place to stop on my first road trip in the West in many years. The name was friendly, transparent, optimistic, and had a touch of jocularity. It sounded All-American, which is how I think of this part of America in general.

Larry had driven down from Missoula, Montana, where he and his wife, Anita Huslin live. He was in a 2021 Ford FX4 pickup truck they’d acquired since I’d last seen them a couple of years earlier. It was their first pickup since moving to Montana 12 years ago, and from it I concluded that they now thought of themselves as westerners.

I met Larry in the 1980s when I did contract reporting for National Public Radio and he was the assistant science editor. He went on to become the National Editor, education correspondent, Pentagon reporter, and fill-in foreign correspondent in Israel. He eventually took a buyout and became dean of the University of Montana School of Journalism. Recently retired from that, he was filling his time as a ski patroller and volunteer teacher–a good tail to a distinguished career.

I knew Anita from The Washington Post, where she worked for many years before also going to NPR, and thence on to other things. Alas, she would not be on our trip down Labyrinth and Stillwater Canyons. She had to work.

As we traveled south out of Salt Lake City we saw Utah Lake out of the passenger-side window as we passed Orem and Provo. The water eventually disappeared and was replaced by sere scrubland sculpted by gullies and ridges. To the southeast were tan cliffs with green and black horizontal stripes. Far to the southwest were mountains.

We got to Helper in the middle of the afternoon. It was bright and hot. We’d both expected that by the last day of September fall weather would be sneaking in, but the only evidence that summer was over—or almost—were occasional stands of trees trees turning yellow and orange.

We turned left off the highway to get to downtown Helper, but when we turned onto Main Street we found it blocked off, with a half-dozen cars and trucks in front of us. Right in front of us was a Sinclair gas station with four trucks from the 1940s in parallel bays, ready to be dispatched. We turned around. We eventually found our Airbnb on Locust Street, one of about 20 identical houses lining both sides of the street.

“Company town,” Larry said.

The house was a bungalow with a concrete front porch. There was a living room with a bedroom off it, and beyond that a kitchen with another bedroom (no door) off it. The rear of the house was a bathroom and a laundry room. The backyard, also concrete, had two porch chairs, and a cat on one of them. The rental folder said the house was built in 1911, but gave no more history.

We brought our stuff in and then headed out to explore Helper.

It had been a coal-mining town, once a big one. A little mining was still being done on the table lands around it. It got its name because trains coming from the south needed to temporarily take on a “helper” steam engine to get them out of Price Canyon, where the town is located.

At the top of Main Street, a triple life-size statue of a miner in faux obsidian guarded City Hall.

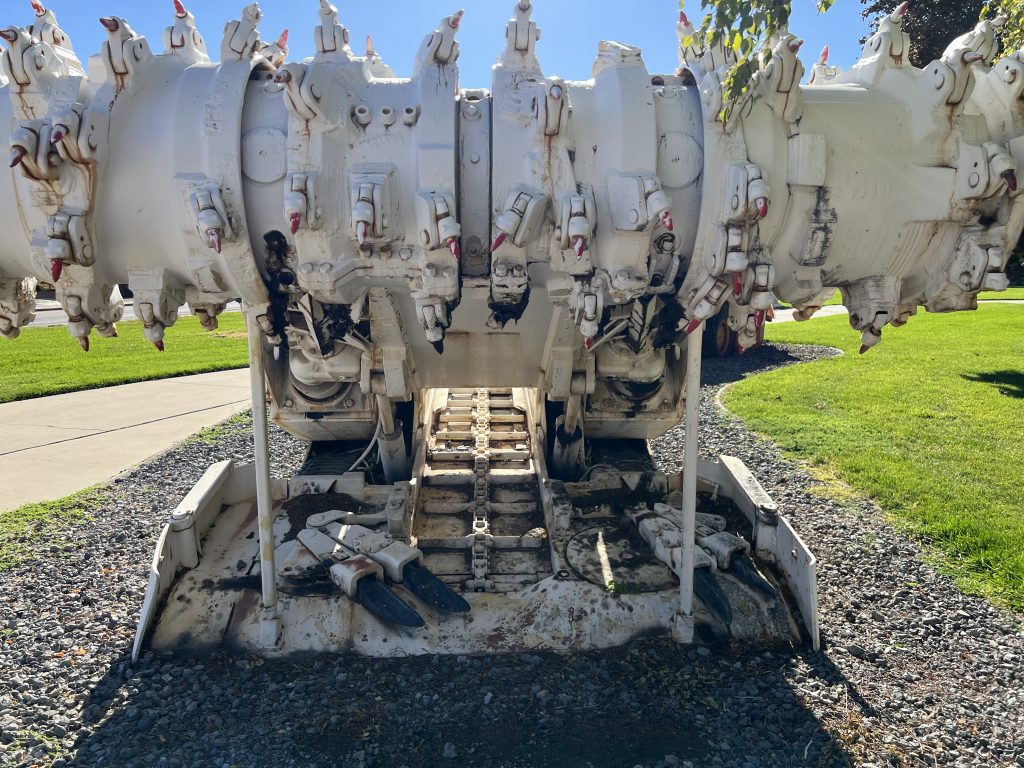

We hadn’t gone more than a few blocks before we came to a grassy park with heavy equipment on it—possibly the Department of Public Works’s yard, except that as we approached none of the pieces looked familiar. It was, in fact, an outdoor display of retired mining machinery.

The coal mines of the “Carbon Corridor” (which includes the towns of Price, Wellington, and East Carbon to Helper’s southwest) are deep mines, not open-pit ones. The machines on display included ones that ground the coal face with rotating or shearing teeth in fixed upper and lower jaws; one that picked up the pieces while simultaneously propping up the ceiling; another that passed the pieces backward to trams that took it to the surface; and ones performing myriad other tasks. Their designs were phantasmagoric; some looked like deep-sea fishes brought to the surface, where they grew to million-X size.

There were several commemorative monuments in the park. One listed “Coal Mines of Carbon County Utah,” with 79 listed, along with their dates and the number of fatalities in their years of operation. The biggest death toll was 277 for Castle Gate #2 and #4, which operated from 1888 to 1970.

More than 200 of those deaths were from the area’s worst disaster, which occurred on March 8, 1924. There were two explosions, the first caused by a miner igniting a carbide lamp that went out, the second by an inspector who did the same thing after the first explosion blew out everyone’s lamps. Later, I saw a broadside on the door of a closed theater advertising a “short documentary,” shown several months earlier, commemorating the centennial of the tragedy.

Driving into town we’d seen people with folding chairs walking toward Main Street and wondered if there was going to be a parade. Now, as we walked on from the machinery museum we passed people returning from downtown, some carrying chairs. We asked a policeman in a cruiser on a side street what was going on.

“It’s cross-country race for the junior high team,” he said.

“It goes down Main Street?”

“Yes, and down this street, too,” he said, indicating the one he was parked on. “They go around three times. This happens twice in the fall.”

We asked about mining operations. He gestured up a ridge on the far side of the highway we’d come in on.

“There’s still some up there, but most of the old mines are sealed. Some have fires in them that are still burning. The biggest mine has a long shaft that comes out of the ground miles down there.” He pointed to the south.

“Is it worth going to see?”

He thought a moment and seemed to be weighing our adventurousness. “Only if you want to see a big pile of coal.”

We soon noticed runners among the people walking toward us, singly and in groups, many carrying water bottles. The gangly adolescents wore singlets with maroon ram’s horns on the chest, probably the school mascot. The girls were taller than the boys.

A few blocks farther on we passed a small park with a playground. Vertical “FINISH” banners stood motionless on either side of the chute. A man was cleaning up what had probably been post-race drinks and snacks. There was an orange water jug on a picnic table.

We turned down a side street to get to Main Street and passed a brick building with a painted advertisement high up on the wall: “Elpe Hotel Rooms 50c and up” and below it was “Try the new natural juice color Orange Crush 5c. In Kringle bottles More Cooling . . . More Refreshing.” The paint was unfaded and seemed restored, although on original lettering.

From the moment we’d entered Helper it was obvious this was a town obsessed with historical preservation.

In less than a block we came to an old hotel that was no longer accepting guests. Through the windows next to the front door you could see a room full of shiny old motorcycles.

Beside the hotel was a commercial garage with the door open. An old blue sports car had its hood up, and a light for working under it was on the ground with its yellow cord snaking across the concrete floor. Behind it were two other sports cars (both 1957 Corvettes, we soon learned), one yellow and one black.

A door off the garage opened into the motorcycle showroom. We wandered in, hesitant and perplexed as to what this business actually was.

A man inside was giving a family a tour of the room, whose walls were covered with signs for gasoline, oil, tires and soft drinks—Mobiloil, Flying A, Texaco, Goodyear, Coca-Cola–well-preserved and from the middle of the last century. When the family departed, thanking the man profusely, we stepped up and introduced ourselves. He was trim, with thinning gray hair and a black tee-shirt with “Get used to different” on it—a good piece of advice, it turned out.

His name was Bob De Vincent, 74, retired from a career as an electronics technician for “the Bell System,” which dated him. He was working on the blue Corvette, and also keeping an eye on the roomful of restored motorcycles—big, small, police, military, sidecarred, three-wheel—that belonged to his younger brother, Gary.

The more we talked with Bob the more opaque this business became. It wasn’t a commercial showroom, although Gary did occasionally sell one of his restored beauties. And advance team for “American Pickers” had been through the week before and loved the place, but they said it wasn’t right for the TV show because not enough things were for sale. The exception were racks of black tee shirts with “Vintage Motor Company” in archaic script on their fronts.

There was also a lot of junk downstairs, in a cellar that went the length of the building. Shelf after shelf held motorcycle parts–gas tanks, carburetors, fenders–and a variety of non-automotive items, including wooden crates that once held dynamite.

I asked what Bob’s brother did that allowed him to acquire such a collection and sell very little of it, but Bob didn’t take the bait.

Cemented to the back wall of the first floor was the most interesting and mysterious item–a sign that appeared to have been written during the Great Depression. It said:

This is only an Emergency Station . . .

No person or persons will be allowed more than 2 meals & 10 hours rest. Meals will be served as follows . . . One meal when checking in & one meal when leaving providing that eight hours have elapsed between meals. (as this is only an emergency station. you are requested to keep moving toward your destination as soon as possible . . .

Persons checking in for the night will be called to make trains.

Was this a service the Lincoln Hotel provided out of sympathy and charitable feelings? Or was it a government service that had been subcontracted out? Bob De Vincent didn’t know, and neither did Roman Vega, the 52-year-old curator of the Helper Museum, whom I called later.

The townsite was originally owned by a Mormon named Teancum Pratt, who settled there in 1881. Pratt had two wives and 11 children with each, and served time in prison for polygamy. He was a farmer and miner who died in 1900 when he fell down a mine shaft.

A marker in the outdoor mining-equipment museum noted that in 1900 Helper had a population of 385 with 16 nationalities represented. “By the 1920s, at least 27 languages could be heard on Helper Main Street,” it said. The population peaked in 1939 at 5,500, and is now about 2,100.

As in eastern coal country, there was lots of labor unrest. In 1903 and 1904, Italian miners went on strike. Mary Harris “Mother” Jones made a visit to support them, but the strike was broken. The Italians were blacklisted from mines in Castle Gate, 12 miles to the north, and many moved on to farm jobs. They were replaced by Greeks.

In 1923, the boxer Jack Dempsey trained in a town eight miles to the west, which was briefly renamed Dempseyville. When he decided against investing in a local mine the name was changed to Coal City. Harry Truman had whistle stops in Helper in 1948 (campaigning for himself) and in 1952 (campaigning for Adlai Stevenson).

By the 1970s, however, most of the mines were closed, and the railroads were less important, too. “When I left in the late 80s all these buildings were empty and some were starting to fall down,” Vega, the museum curator, said of Main Street. “There was a big homeless problem.”

In the early 2000s Helper reinvented itself as an artist colony, with summer courses and eventually a year-round population of painters, sculptors, and fiber-artists. Today, there’s an arts festival in the summer, a film festival held immediately after Sundance, a vintage-car show, and a Christmas festival and parade. Paintings by local artists hung in a gallery above the restaurant where Larry and I had two meals. (It also had once been a hotel.)

Vega returned to Helper in 2013. He’d served at the Army Logistics University in Fort Lee, Virginia, where one of his tasks was to work in the museum. Back home, he volunteered at the Helper museum for three years. When the director quit after the pandemic lockdown, he was appointed.

“It’s been really great to see the city kind of reinvent itself,” he said.

Everyplace we walked in Helper the past was on display in its restored finest. There was lots of old neon and earnest advertisements, with a little contemporary messaging (whose point, to me, wasn’t clear) thrown in.

At the end of Main Street was the Continental Oil Company–Conoco–station, which had become an Airbnb. A tow-truck was ready for dispatch. In the office, a four-blade desk fan was ready to turn. The price of gasoline was 38 cents a gallon.

I looked back down Main Street.

In the distance stood the timeless cliffs that were part of the town’s reason for being. The main drag, straight as a spinal column, celebrated a life that had been dead for most of a century. At the far end, a car was heading toward me. I’d soon have to step aside.

Helper was a living thing caught in amber, and still moving.

Charles Kuralt of the written word. Not to take the comparison too far.