An unusual feature of Labyrinth Canyon is a stretch of the Green River called “Bowknot Bend.” It’s a six-mile loop that long ago would have become a dry oxbow if the river didn’t have to cut through thousand-foot cliffs in order to take a more direct route.

Larry and I got there on our third day out. We left hiking shoes out and ready, as well as trekking poles, and other things we might want on a walk. We planned to hike up the right-hand wall of the canyon to the saddle, where you can see the two sides of the loop.

In his account, John Wesley Powell describes the feature this way:

About six miles below noon camp we go around a great bend to the right, five miles in length, and come back to a point within a quarter of a mile of where we started. Then we sweep around another great bend to the left, making a circuit of nine miles, and come back to a point within 600 yards of the beginning of the bend. In the two circuits we describe almost the figure 8. The men call it a “bowknot” of river; so we name it Bowknot Bend. The line of the figure is 14 miles in length.

The description and distances (plus or minus a mile) fit the feature we paddled around as well as the now-dry oxbow just downriver where we camped later that day. Powell’s statement that his party went around two large loops of river leads me to the conclusion that the second loop was cut off sometime after his 1869 trip, as the river no longer goes there.

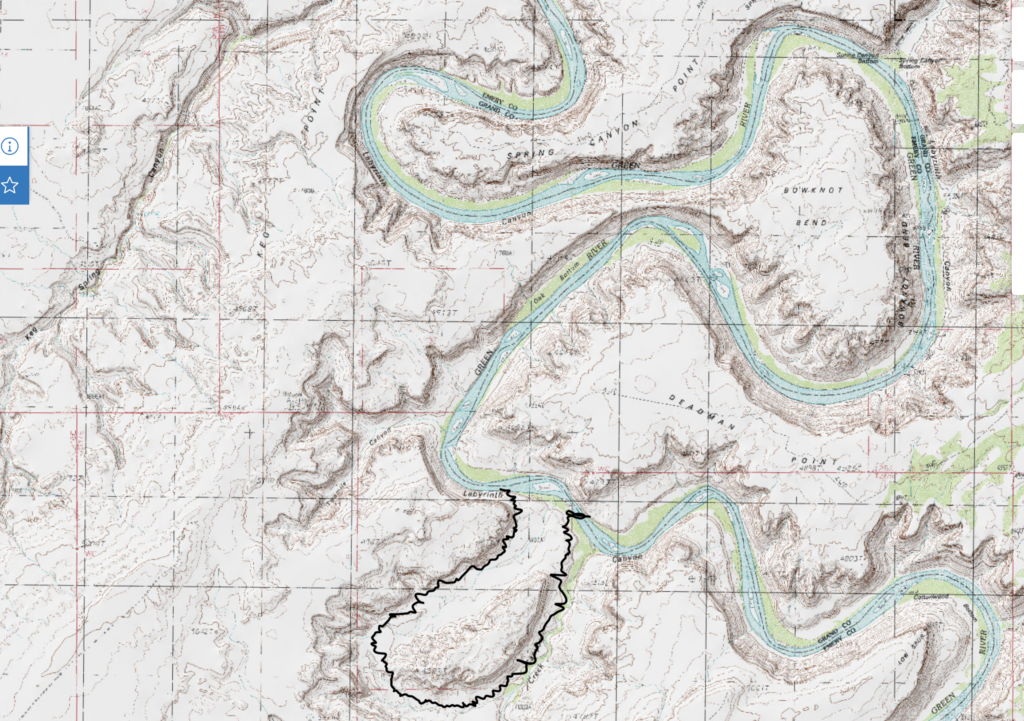

In the map below, the squiggly line I’ve drawn shows where the second loop of river might have run. In any case, “Bowknot Bend” on contemporary maps denotes the bigger oxbow we paddled around, although technically it forms only half a bow.

Four other boats had pulled ashore on the right bank at the place where a trail led up a boulder-filled slope to the saddle. At least two of the boats carried people who’d been on our shuttle trip to the put-in–fit retirees, more than half of them women.

We walked up the trail, which was marked by occasional cairns. In a few places rocks had been arranged to create steps. In a few places we had to climb on all fours. There were two or three dangerous spots, but the people ahead seemed to have had no trouble, so we soldiered on.

When we got to the top the view was spectacular (and it had been pretty good on the way there).

“It’s the only place in America where you can stand and see a river flowing in two directions,” Larry said.

“Is that true?” The assertion seemed unlikely, although it occurred to me he might have read it in a book.

“Well, I don’t know,” he said sheepishly. “There are probably other places you can do it.”

We looked down on the outbound arm of the bow, where we’d be in a few hours. Three canoes passed by. They were tiny. No one looked up. On the far side of the river from them was a river bottom impenetrable with tamarisk.

On a red sandstone wall exactly where someone would stand to take pictures was a name and “9/24” scratched into the rock. We wondered what century it was from until we saw next to it an inscrutable drawing and the number “2024.” So it was from September 2024–the month before we were there. Amazing and appalling.

As we started to descend we ran into three people. One was a big man with wild Einsteinian white hair. He asked Larry as we passed, “Are you a computer programmer?”

“No,” Larry said.

“I thought you might be. We have the same shoes. I’m a programmer. Everyone in my office wears them.”

“No, not a programmer,” Larry said. “Keep guessing.” I was tempted to give him Larry’s impressive 25-word biography, but held my tongue.

Back in the canoe, we paddled around the Bend, looking for the remains of uranium mines and even an old airstrip that the guidebook said were on the right bank. We could see none of them. What we did see is what Powell saw and described.

There is an exquisite charm in our ride to-day down this beautiful canyon. It gradually grows deeper with every mile of travel; the walls are symmetrically curved and grandly arched, of a beautiful color, and reflected in the quiet waters . . .

Powell’s account says the party camped “on the south side of the great Bowknot” that night–somewhere below where we would soon pitch our tents. “As we eat supper, which is spread on the beach, we name this Labyrinth Canyon.”

Like Greek gods, Powell and his men that day gave two places the names they still bear on maps.

* * *

If you travel in silence down a Utah canyon, whether on water or foot, an ironic fact eventually reaches consciousness. While everything in sight is the product of breaking and falling, you never hear anything break or see anything fall. Silence and stillness are the canyons’ natural state.

How can that be?

The answer, of course, is geologic time. Change in this part of the world happens so slowly it’s imperceptible to the human observer. Major Powell, the geologist, never loses the sense of wonder that it’s so. Of the buttes and spires he passed he wrote: “The rain drops of unreckoned ages have cut them all from solid rock.”

But as soon as you’re convinced that nothing happens quickly you run into evidence that sometimes it does. That was the case at the place where we camped after paddling around Bowknot Bend.

We came ashore at the downriver end of a dry oxbow that, as I argued above, I think was cut off from the river sometime after the Powell expedition of 1869. We unloaded on an immense sandbar, the biggest we’d seen.

The upstream entrance to the ancient oxbow was so obscure that we hadn’t seen it, but there was no missing the downstream end. It drained a place called Horseshoe Canyon, which has a watercourse called Barrier Creek running down it. None of this registered with us; we were just glad to find dry sand.

After we’d set up the tents, chairs, and the table Larry carried a chair across the alluvial plain into the shade to read. I headed up the dry oxbow to explore. The stream bed was damp, but there was no standing water.

The sun was dropping behind a rock formation between the oxbow’s two limbs. The formation was flat-topped and had a pointed-oval shape. It was called “The Frog” according to the guidebook, which said the reference was not to an amphibian but to the soft underpart of a horse’s hoof, which is called the “frog.” The name made sense, given that we were in Horseshoe Canyon.

As I walked away from the river the creek narrowed. Newly cut walls of sandy bank were 12 feet high in places, with roots sticking out of them all the way down.

In several places, trees had eroded from the bank and fallen into the channel of the creek.

Clearly, there’d recently been a monstrous flow through these parts. I imagined what it must have looked and sounded like as rushing water and tumbling rock redesigned the stream’s course. Our campsite–if it even existed before that storm–would have been washed away, along with anybody on it.

Canyons are quiet and peaceful except when they’re tumultuous and violent. I was disturbed by my lack of situational awareness when we chose this wonderfully bare sandbar as our stopping place. Spooked, I walked back to the river on the bank, not in the stream bed, climbing through tangles of matted vegetation.

The darkening sky was still cloudless and there was no rain in the forecast. I didn’t suggest to Larry that we move the tents to the inland edge of the sandbar, from which we could scramble to higher ground if we heard a riverine freight train in the middle of the night.

Sitting around the fire, I hoped for fair weather for us tomorrow, and fair weather for everyplace up Horseshoe Canyon that night.

* * *

The canyons may appear empty, but traces of man are all around if you know how to look, and where. By and large we lacked that talent and knowledge.

We stopped at a couple of spots to look for an abandoned ranch building, a cliff dwelling, an Anasazi granary mentioned on the map. We encountered a lone woman on an oar raft and asked the way to Indian ruins in Jasper Canyon. “You’re past it. It’s back there,” she said, pointing upriver.

If we’d looked harder and gone farther from the river we might have found some of these sites. The most unusual one, however, I didn’t learn about until after the trip.

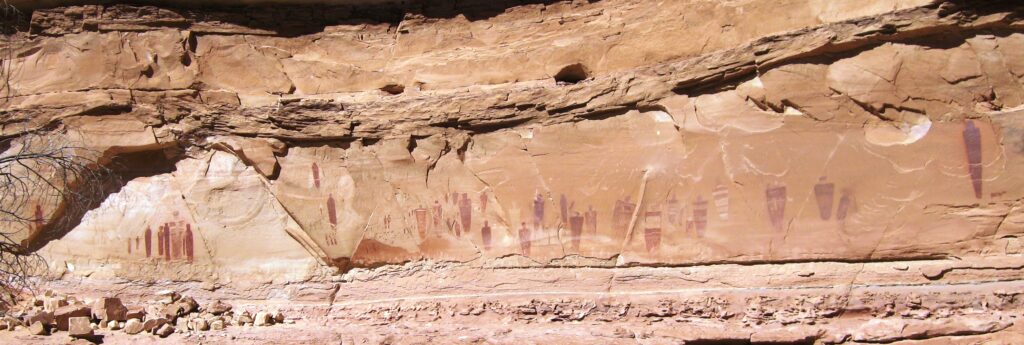

The Great Gallery of rock art was about 13.5 miles up from the mouth of Horseshoe Canyon, where we camped. That’s a long hike, and not doable roundtrip in one day. Going there would have required a radical restructuring of the trip.

The Great Gallery is 200 feet long and 15 feet high, and has more than 20 anthropomorphic figures painted on a rock face. (That makes it a “pictograph”; a “petroglyph” is incised into rock). It’s been dated to A.D. 400-1100. An antelope-skin bag containing tools for making arrowheads (chert blanks, antler flaking tool, sanding stone), as well as an emergency ration of marsh-elder seeds, eroded out of the sand in 2005. It was dated to A.D. 770-970.

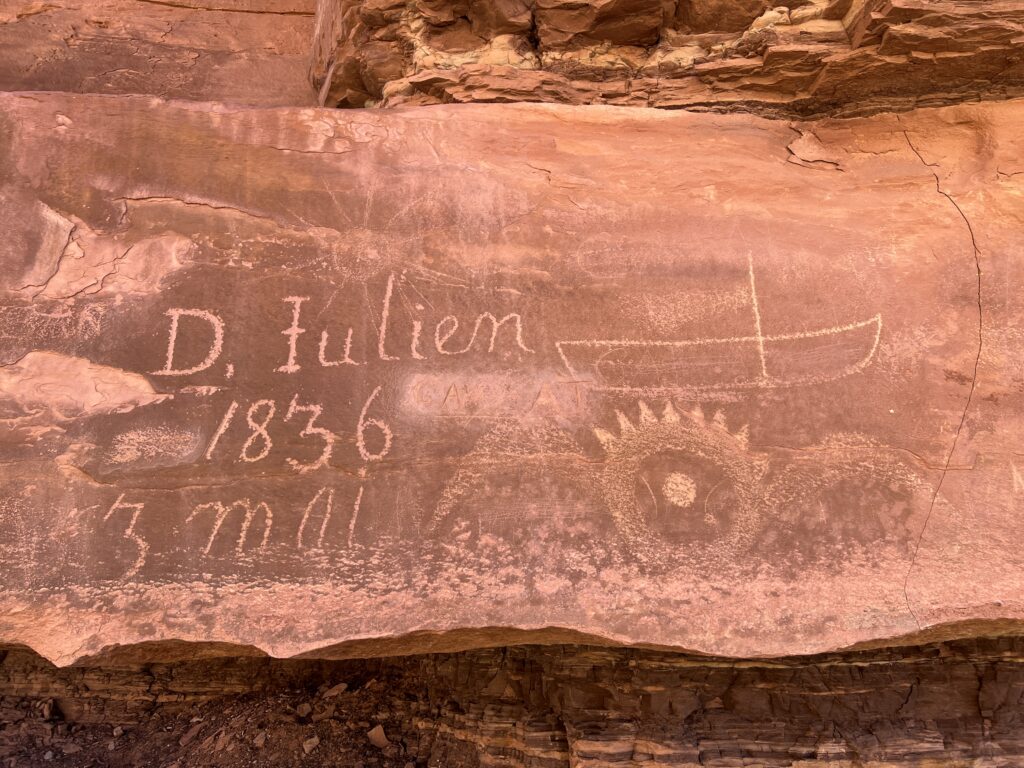

It would have been nice to see some Indian rock art. However, we did see one of Labyrinty Canyon’s better-known pieces of graffiti–the pictographic work of Denis Julien, a French Canadian fur trader from 1836.

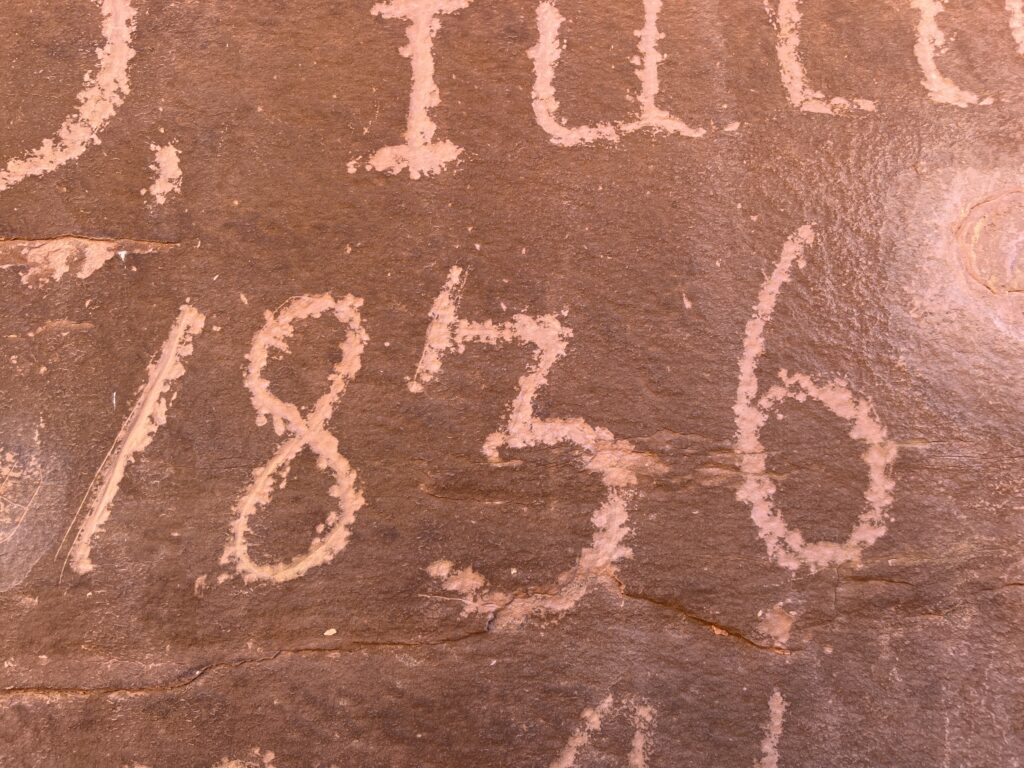

Eight tags by Julien are known, although the authenticity of two is suspect. Many aren’t easy to find and one wasn’t noticed until 1931, almost a century after it was made. We’d missed one of Julien’s offerings the previous day, and were determined to find the next one. It turned out that wasn’t hard.

We knew we were close when we saw a canoe pulled up on a mudflat near piles of flow-deposited debris. As we landed two people appeared who’d just come down from the inscription. They gave us directions, which were not terribly clear but that we figured would get us close. The most useful tip was to look for a “plaque,” which turned out to be a sign on a post telling visitors the graffiti was on the National Registry of Historic Places and that adding to it was a federal crime.

We found it above a dry creek and climbed up to get a good look.

The main features are “D. Julien 1836 3 mai”–the capital “J” in an old orthography that makes it look like an “I.” Next to it are drawings of a boat with a mast (and possibly a diaphanous sail), and a sun-like image that might also be the body of a winged creature. There’s evidence of a few other bits of graffiti that someone had taken off with fair success.

This inscription was apparently first seen by a steamboat operator in 1893, with a photograph of it published in Outing Magazine in 1905. There’s another that reads “1836 D. Julien” in lower Cataract Canyon, which is now covered by the waters of Lake Powell.

What’s most surprising about the inscription we saw was that it was made before the one we’d missed the day before, which is dated “16 mai 1836.” That means Julien was traveling upstream on the Green River. The canyon both creates and channels wind; the idea there was enough to sail by is remarkable.

A surprising amount is known about Julien. He was born about 1772. His wife was an Indian who went by the name Catherine. The records of a cathedral in Missouri note the baptism of children in 1793, 1798, and 1801. In 1808, Meriwether Lewis, governor of the Louisiana Territory, described him as “an old and much respicted trader among the Iaways.”

In the Utah Historical Quarterly in 1996, historian James H. Knipmeyer wrote: “His name appears in the ledgers of St. Louis fur baron Pierre Chouteau in 1803 and 1805, the latter instance to trade with the Indians in present-day Iowa. From 1805 until 1819 he owned property south of Fort Madison. Mention of his trade with the ‘Ioways’ was also made in records for 1807, 1808, and 1810. His name is listed as a witness to the Iowa Treaty of 1815.”

He owned property in Prairie du Chien on the Mississippi River (in present-day Wisconsin) in 1821. In 1827 he was in a party that recovered cached furs on the land of the Ute Indians in western Colorado or eastern Utah. Where and when he died is lost to history.

What’s certain is that Denis Julien got around and left his marks. Today, they unwittingly raise the question: “When does an act of desecration become an artifact?” One answer is: “When it’s 188 years old.”

Elsewhere on the trip we passed tags from the 1940s that the map and guidebook found worthy of interpretation, but that I’d file under vandalism.

Recent Comments