Six years ago I took a sailing course in New Zealand run by the National Outdoor Leadership School, an organization headquartered in Lander, Wyoming, at the foot of the Wind River Range. NOLS runs expedition-based courses—some lasting a semester—around the world for about 25,000 students a year.

In the New Zealand course nine students (most in their late 20s), two instructors, and one instructor-in-training, sailed two 40-foot sloops in the Marlborough Sounds at the north end of the South Island for two weeks. The course was rigorous and emotionally trying; sailing is serious business that masquerades as recreation.

On the strength of that experience I bought an 18-foot pocket cruiser and berthed it at the mouth of Jones Creek, a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay east of Baltimore. The boat turned out to be a lemon with bad luck. The chainplates on deck leaked rainwater into the tiny cabin; the centerboard trunk sprung serial leaks; a freak windstorm blew the boat off its trailer one winter, bending the mast and wrecking the rigging. I sailed it fewer than 20 times—and not once for two seasons.

In the spring of 2023 it was finally fixed and in the water, but my sailing skills and confidence were badly in need of rehabilitation. So, I signed up for another NOLS sailing course.

This was an “alumni course”—more casual and less austere than the one in New Zealand. But it was still a course; we were advised not to think of it as a cruise, or even a vacation. We’d be in the Ionian Sea off the west coast of Greece—one boat, six students, two instructors, nine days, and no ban on going ashore or drinking alcohol.

I’d never been to Greece. My knowledge of ancient history and Greek mythology was slim (although I did memorize the Greek alphabet at summer camp when I was 13). I learned a bit about the history of the region in historian David Abulafia’s “The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean.”

The book’s 783 pages can be summarized as: “Endless war in a beautiful place.” When I told one of my Italian cousins about my plans she replied with a hint of this history: Your trip sounds wonderful. The weather should be lovely and the winds brisk. I’ve always considered the Ionian Sea Italian, but I will share it with Greece 🙂

Here’s how it went.

* * *

Monday, May 1, 2023

We left Villa Diodati, where we’d spent two nights, about 8.30 in the morning in a van and a rented Kia stuffed with duffels, bags of food and water, and a cardboard box with three kinds of leftover pizza.

Our teachers, Dave Hanaman and Nick Braun, were unable to move the boat from its home berth in Vlikho Bay to Nikiana, which we looked down on from the villa. Even this early in the season—many tourist destinations are opening only next week—all the public slips were taken. We suspected charter companies big-footing them.

As a way to give permission to step aboard, here’s who we were.

The lead teacher was Nick Braun. Like all the NOLS instructors I’ve met—I also took a Wilderness Medicine course a couple of years ago—he has a long and eclectic resume. He’s the son of an immigrant from Austria; a student of German and environmental education who studied abroad in college and got a master’s degree in Sweden. Once an employee of The Nature Conservancy and now a firefighter in Colorado (where he also helps manage a ranch), Nick works remotely fulltime in the alumni office at NOLS. He was gored by a bull on an expedition in Australia a decade ago. He survived. He teaches backpacking, kayaking, and sailing courses. Needless to say, he’s a person of immense energy.

The other instructor is Dave Hanaman, a former Navy intelligence officer who after leaving the military started and sold a company, retired, and later returned to work. He now heads a “clinical research organization” (CRO to you all in health care), which runs digital clinical trials of drugs, medical devices, and non-pharmaceutical therapies.

The students were: Hugh Hudson, an engineer who now works as a “problem solver” for a consulting company (a source of mirth onboard, where problems aren’t rare); his daughter Emma, an outdoorswoman who runs programs for Outward Bound in the Pacific Northwest for troubled youth; Dave Bock, an arborist for the city of Austin, Texas, who grew up in Chicago sailing boats on Lake Michigan; Brian Le, who escaped Vietnam at 16, became a nurse anesthetist in the United States, and lived in Bangor for 15 years before moving to San Francisco (and that’s not the half of it); and Sasha Lennon, who’s a potter in western Maine (https://sashalennonpottery.com). (She’s also the daughter of an anesthesiologist my nephew has worked with in Portland, Maine.)

And me.

We arrived at Vlikho, five miles south of Nikiana, about 9 a.m. and took possession of our boat. It’s a 42-foot German-made Bavaria sloop named “Freedom”; its name is written in English and Greek on the hull. It’s nearly new; Nick thinks it’s a 2022 model. It is bigger than the boat I sailed in in New Zealand, and better appointed (befitting alumni, I thought).

There were two heads and a bigger galley. The forward berths each accommodated two (intimately), and the aft stateroom had its own head. The two instructors chose to sleep on converted beds in the saloon. The floor was unscarred faux parquet.

We loaded up. I packed the refrigerator. This required triaging out the cheese when I discovered the cold cuts weren’t stowed when the box was stuffed. Provisions for this trip are a world apart from the New Zealand course’s menu of carbohydrates lightened with tomato paste, a few slices of onion, and no fresh vegetables.

The charter company is named Sail Ionian. It’s owned by an English family and run by the second generation. A man helping our final preparations, Billy, came and went from the dock as he attended other boats. He kindly answered a few questions.

The company has 45 boats in its charter fleet, and it takes care of 40 private boats not for hire. It’s the only charter company in Vlikho; the whole waterfront is its territory.

Billy has a broad working-man face, and the accent to match. He’s from Preston, in the north of England near Liverpool. He started out as an automobile mechanic and eventually got a job on the Liverpool waterfront. From there he made contact with the Sail Ionian folks. He moved to Greece 11 years ago.

He didn’t speak a word of Greek when he arrived and also didn’t know how to sail. Now, he speaks passable Greek and talks as if he’d won the lottery: “Not many people in my part of the world get to move to a beautiful place like this.”

We cast off at 10.45 and headed out into the cove beyond the marina. We each got a turn at the helm driving the boat forward, backward, and in circles. For 42 feet it was responsive and fast-turning, with almost no prop-walk in reverse.

It rained on and off, never hard or unpleasantly. We had a dodger and a Bimini, but we took the Bimini down when the rain let up and it became more important to see our surroundings than to keep dry.

Vlikho Harbor is shaped like the candy at the end a lollipop stick. We went down the stick to the open bay, which was the water we’d looked down on from the villa. It was a perfect place to practice sailing—open, windy, no commercial traffic, few sailboats, and no obstructions (the chart told us) except for a two shallow rocks and a submerged wreck next to them.

Nick and Dave showed us how to work the lines, raise the sails (both self-furling, so they move in and out, not up and down), how to tack and jibe. Only Sasha got a chance to jibe, but we all tacked numerous time when we got our 15 minutes at the helm.

It was breezy and we made 7-8 knots under sail. We furled both sails and saw how the performance of the boat wasn’t hurt with smaller sail area—and may have been better. So, my first lesson of the course was that furling is not just for safety, it can also enhance performance.

We made the harbor at Spartakhori about 5 o’clock, docking bow-in to a stone bulkhead beside three other boats. Bow-in is preferred because the water gets shallow close to the wall and could threaten the rudder.

Five of us—Sasha, Hugh and Emma (the father-daughter team), and Brian (with whom I’m again sharing a bedroom, as at the villa) walked up the switchback single-lane road to the village at the top of the ridge. We passed a bronze monument to a man in uniform who died fighting organized crime in 1997, according to the camera-based translation app on Emma’s phone. A bas-relief showed two open boats, one pursuing the other.

We went by a schoolyard with two mothers and four children, two on swings over a synthetic play surface, with the Greek flag fluttering overhead. We went up to a church, but it was locked. We passed what appeared to be an old government building with a sign saying that rehabilitation was taking place with the help of the European Union.

We passed Tropica Pizza and a souvenir shop, both doing no business. At an open-air bar under a plastic cover only old men drinking and smoking.

The village was mostly small concrete houses painted white and trimmed in color. They were in good shape in the main. Trees were putting out fruit that was so far from harvest that we couldn’t identify what they would become. Some of the stone-paved streets needed work.

Clearly tourism is the main business, although there must be some fishing. We’d passed a small fishing boat coming in, and there were many at the two marinas with piles of fine-mesh yellow netting piled on deck and quay. I wondered what they were after. Maybe sardines.

We descended the hilltop on a road whose Achilles heel was hairpin turns, not holes. In our absence, the others had laid out hors d’oeuvres—red wine, stuffed grape leaves out of a jar, carrots, cucumbers, potato chips, and green and black olives—before a dinner of cheeseburgers made by Dave the instructor. He washed the dishes too, quite a generous introduction to the cruise.

Before the instructors took over the saloon for themselves at 9.30 p.m. we reviewed tomorrow’s weather forecast. We knew it was going to rain for about 36 hours, but now the prediction included the possibility of “cyclonic winds.” Our destination was Sivota, a desirable place under fair skies we are told, but one that may be especially sought in the weather we’re expecting.

We plan on getting there by noon.

Tuesday, May 2

I asked Brian what time it was at 6.30. There was not enough time to try to go back to sleep, so I got up without a lot of debate. We had breakfast of dry cereal, yogurt, fruit and coffee laid out by Nick. These instructors are very solicitous—no leaving all of the grunt work to the paying students.

It was the first day that most everyone used the heads post-prandially in the space of an hour—a test of self-consciousness and mutual sympathy.

We motored out to the open water, hoping the weather wasn’t so bad that we’d have to hightail it to Sivota to wait things out. It turned out to be a great day for sailing. We passed a cliff of brindled rock with a huge half-circle of blackness at the level of the water. It was a cave, one of the biggest in Greece, someone said. But we didn’t go over to explore; we had things to practice.

As before, we took turns at the helm, setting the main sail and jib and then tacking without adjusting them. This seems to be an important skill, good to know when beating up wind. Two of us tried jibing, but I haven’t had a chance yet.

There was enough sailing traffic to require strategic decision-making; it also gave Nick and Dave reason to talk about right-of-way and rudimentary rules of the road. (I did remember some of this.) The wind picked up to small whitecaps. We reefed the sails, our speed maxing out at 7.8 knots according to the app-recorded route we reviewed later. The wind reached 20 knots right before we pulled in the sails and headed for the harbor.

We’d taken a spin into Sivota before the sailing lesson to reconnoiter the anchorage. The piers were already full of boats. We looked at the one where we thought we’d tie up and it appeared that tricky docking was in our future.

Dave called the person in charge of that part of the harbor before we returned in the afternoon. We were told to approach a different dock and pull in between two boats, each with a pair of Englishmen on them.

Nick did a masterful job. Billy, of Sail Ionian, was on the dock helping with the lines. It wasn’t clear why he was here, but someone later speculated it was to keep an eye on the company’s on-water investment. In the harbor were 10 yachts flying the company’s banner in their shrouds.

Late that afternoon a woman who worked for the charter company (and was wearing a Bavarian Yachts tee-shirt) asked to come aboard to attach a tracking device to one of our batteries. It would allow people in the Sail Ionian office to observe our position and track our route and speed in real time. We’d seen black ship icons on our electronic chart and wondered what they were; it turns out they were Sail Ionian vessels equipped with this device. So, we’d briefly been a ghost ship; the company was putting an end to that.

“But we’re Freedom,” Emma said. “That’s why we didn’t have that device.”

“It’s very Orwellian,” I said. “Now we have what the Soviet communists used to call a ‘new kind of freedom’ .”

“I wonder what those things are called,” someone said.

“Big Brother.”

After a mid-afternoon lunch we had a couple of hours to kill. Most of us sat in the saloon doing various things. Dave, the instructor, who sleeps there at night, retired to the forward vee berth for a nap, and Brian went ashore to walk around.

Nick kindly spent more than an hour helping me with the Navionics and Windy apps. I still had routes through the Everglades I made last fall before the Tonino trip and hadn’t been able to remove. He showed me how to delete them, make new ones, and other useful tasks. We also explored both the windy.com and the windy.app apps. We didn’t learn until the end of the session that the reason I couldn’t get a screen I’d see on Nick’s iPad was that I was on the wrong app. Windy.com and windy.app—why isn’t one of them trademark infringement?

This was very nice of him.

We ate at the restaurant run by the people whose dock we were on This apparently isn’t required but is appreciated. NOLS paid.

We got local fish dinners—red snapper, dorado, calamari, octopus, and sardines—with vegetables, French fries, bread, and spicy feta. Also beer and wine, although in general this is a temperate group. Our waiter, Ioannis (which he said is the name of 40 percent of Greek men), was witty and full of Greek chauvinism.

Most names in the Western world were originally Greek—Nicholas, Philip, Peter, John. Greece (and by that he seemed to mean Attica) has better yogurt than northern Greece and the Balkans. Macedonia conquered the whole world except Attica. Greece has more guns than Texas. That sort of thing.

We were on the restaurant’s second-floor porch. It had clear vinyl walls and was not really indoors. It was cold when we arrived at 6.30 p.m., but after 8 when the crowd arrived it warmed up. A real storm was underway and we were glad we’d come in early.

As rain ran down the vinyl curtain we watched a yacht that had dragged its anchor being blown toward the dock. A Zodiac raced to help in the near darkness. Fifty feet before crashing the anchor held.

The boat started its engine, disappeared, and after a while reappeared. It moved stern-first toward a finger dock across the harbor, trying over and over to keep a safe course in the blustery weather. Night fell before we could see the end of the drama. But all was well the next morning, so it must have been successful.

“They’ll be doing laundry today,” Dave the instructor said as we had breakfast the next day at a bakery in front of where all that had been happening.

The weather forecast was for thunderstorms. We didn’t want to be a sailing lightning rod, so we were leaning toward spending another day in Sivota.

Wednesday, May 3

We slept late, but by 8.30 everybody but one was up. People went off the boat as they were ready.

The village is a U-shape around the harbor. The arm across from us is the longer and has a row of shops—perhaps 20 in all—catering almost exclusively to the tourist trade. They include two small food markets, a half-dozen restaurants, a bakery, several gift and sundry shops, and several real estate offices.

We all gathered in a bakery the first group off the boat had stopped at. We drank coffee and ate pastries until after 10. At one point Brian bought a loaf of peasant bread and a jar of marmalade and we all dug in for dessert. The leaders formalized what was obvious—we were staying the day and another night here, waiting for better weather.

The weather, in fact, was changing about every half hour from overcast, rainy, broken-sunny, and windy. It was a good call.

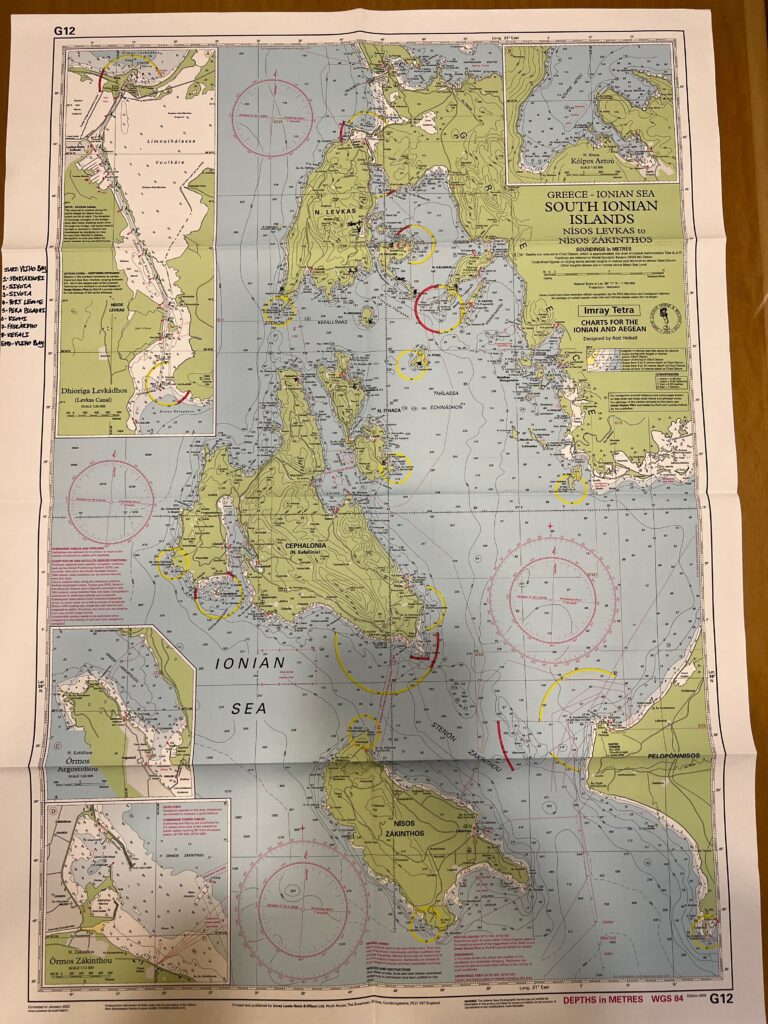

I headed off in search of a nautical chart of our cruising ground—the charter company had lent us one, but I wanted one of my own—but couldn’t find one. However, I did find a shop that sold olive-wood kitchen spoons and spatulas, and a small pair of salad implements, which I bought.

By the time I was back on the boat a list of chores had appeared on the teachers’ whiteboard. People checked a box and put their name next to the task. The work was underway.

I took sweeping the floor, with a whisk broom and dustpan on my knees. I covered the stateroom floors, the saloon floor, the cockpit and the aft boarding platform. As a late arrival I’m glad I got one of the harder tasks.

When we were done we sat around for a while and then headed out on a hike. Our destination was the point of land at the entrance of the harbor on our side of the U. It wasn’t raining, but we heard intermittent thunder and there were storm clouds and rain across the open water. Three ranks of low mountains were visible but featureless in shades of gray.

Billy had told Nick there was a path to the point of land that was an alternative to the paved road. It paralleled to the road briefly, and we headed onto it as soon as we found it.

A two-abreast path soon turned to a single-file one, and then to a barely visible one that required holding back branches of thorny bushes for the people behind. Wildflowers were out and we passed through an area with the scent of spice bush and mint whose source we couldn’t find.

A true path ran out long before we got to either the point or to a swimming place midway along the route that Billy had mentioned. We found what we thought was the latter. It was clearly on private property, but this didn’t bother Nick, who was in the lead. (Dave the instructor had stayed behind on the boat). We descended a set of stone stairs to a cement platform built on the rock.

As we’d set out, Sasha, Emma, and Brian had all said they planned to swim. It was overcast and cool, but they were good to their word.

Brian swam out into the choppy deep-blue water; the women dove in, did a few strokes and headed back to the rocks. A piece of bent stainless steel pipe that emerged from the rock just above the water line turned out to be a hand-hold.

We climbed back up the stairs and turned right onto the remnant path. Eventually we came to a fence. Billy clearly hadn’t been down this path recently, or had gotten bad information. We considered turning around but instead headed uphill along the fence until we got to a gate.

“It’s somebody’s back yard.”

“Does it open?”

“The gate’s welded shut.”

We were about to leave when I stepped up to the top step to take a look for myself. On the right-hand gate post was an open padlock, suggesting the gate had been lockable in recent memory. I pushed on it and it opened.

We went through it and turned right, on a stone walk below a stone wall. Eventually, though, the walk’s elevation rose and we came into view of a house on the left where a car was parked. A few seconds later we saw two women, one blonde, the other dark-haired, sitting on a deck in front of computers.

It occurred to me to try to just sneak by hoping they wouldn’t see us, but of course they saw us. One person suggested we turn around.

“Just keep a smile on,” Nick said.

Our earnestness—we were a group of varying ages and both sexes out in the rain—was obvious. Nick, in the lead, asked the women about a route to the road and said something about being told there was path to our hoped-for destination, the point at the mouth of the harbor.

The dark-haired woman got up, stepped forward and welcomed us. She said there used to be a public right-of-way, but new property owners had built on it and blocked it off. The municipality had recently asserted the existence of a right-of-way and things were in some sort of litigation. In any case, we were fine to be walking on her mini estate, she said.

We proceeded until we came to another obstruction. This time we walked down to the shore, looking for a way to proceed onward, but there wasn’t one.

We gave up going to the point, and as a consolation prize headed back along the shore in search of a way onto a bald promontory that looked like a place with a good view.

We didn’t find a path to that destination, either. Instead, we continued down the shore, which was covered with ledge and boulders of porous gray volcanic rock stuccoed with a white calcified coating that was worn off in many places.

Where the gray stone was bare it was rough, and in places worn to blades and points. It was probably the most dangerous surface I’d ever walked a long distance on. A stumble would have been bloody mess, and even breaking a fall with a hand would have created a nasty wound. Brian was in flip-flops and Emma in sandals. I was in shorts and wished I’d worn long pants. I also thought longingly of my bike gloves back on the boat as I picked my way through the boulders.

After half an hour we got to a place where the shore became a cliff. It might have been possible to pick our way along the top, but now the hazards included a tumble 30 feet into the sea. Nick declared it was time to turn around. We hadn’t reached either of our destinations. But we’d gotten farther than most of the group expected.

It was notable that Nick, the leader and person who’d have to solve the problem if one of us got hurt, at every point but the last expressed a desire to keep going. His willingness to walk on private property, seeking forgiveness with a smile while also seeking permission, isn’t what most organizations that take fee-paying strangers on trips advocate or allow.

Maybe it’s NOLS or maybe it’s Nick, but this attitude meets with my enthusiastic approval. And his decision to turn around when we did was, of course, the right one.

We made it back to where we’d come onto the shore in 17 minutes—half the time it took us to go out. Up on the road, I congratulated myself and everyone else in making it across killer rock without bloodletting. Hugh held up his right hand to show a small cut between two fingers, so it wasn’t quite true. But it was true enough.

We returned to the harbor on the road in steady rain. We passed many houses newly finished or under construction, all vacation properties. The signs at the driveways were in English—Blue Coves, Villa Emma, Villa Ella, Dynasty Estates.

We were wet when we got back on the boat. My running shoes—the only footwear besides my sandals—were soaked, and given the weather report, likely to stay that way. Rain was predicted for the whole next day.

We had dinner at the same restaurant, with the same entertaining waiter, who seemed to think I was a famous person he couldn’t quite name. We wanted to try a different dining spot—there were several—but Dave the instructor had been told on an errand in town that the expectation was that if you stayed on the restaurant’s dock you’d eat at the restaurant every night. We stayed until after 10 o’clock, which in this season of retiree sailing meant we closed the place down.

We did passage planning in the saloon when we got back to the boat. We’d sail tomorrow, rain or not.

Thursday, May 4

It did rain all day.

We went out of Sivota into the open water. There were a few sailboats in view and more appeared as the morning progressed. Visibility was good but the sky was overcast the whole time and we sailed with running lights.

I took the helm early on and drove for a long time. The task was to keep on course. We were close hauled. I did a good job, but there were few decisions to made.

I’d said in the before-cruise self-introduction we all made that one of the things I wanted to get out of the course was to learn how to heave-to. I’ve never reefed the sails on my boat, and doing that single-handed requires heaving-to. I needed to learn the maneuver before my ignorance became dangerous.

Today was the opportunity.

We each took a turn, moving into hove-to using the jib principally as the brake, and then out of hove-to with a jibe. For me it’s confusing to the turn the wheel at the helm in the opposite direction from what I’d do with the tiller on my boat. But I think I have enough knowledge now to try it on “Windlass.”

When we were done we headed to our anchorage—Port Leone, an abandoned village on an uninhabited peninsula. An earthquake in 1953 had driven the inhabitants off.

It was blustery when we sailed into the harbor near the village to look for a place to anchor. The original plan was to motor, but the teachers wanted us to push our limits. We feared the place might be full of boats, but nobody was there. Hugh was at the helm and did a great job. I wonder how I would have done.

The remains of a windmill and a second similar structure were visible on the point leading to the village’s harbor. They looked like ruins in a Thomas Cole painting. A nub of land turned the harbor into two coves. We tried to anchor in one, but the anchor failed to hold four times, so we rounded the nub and tried on the other side. There the anchor held.

Dave the instructor and Brian went ashore with two long lines, which they turned into one using a bend we’d been taught in a break in the action earlier in the day. They made the boat fast.

We tidied up, left our sopped clothing under the Bimini, and went below. We’d skipped lunch, so we moved right into cocktail hour; it was after 5. We’d explore the abandoned village tomorrow.

Friday, May 5

We woke up and the sun was out. We felt the thrill that people on whale ships and naval vessels of the Frobisher era must have had after days of rain—except that they’d really had a reason to feel miserable, unlike us.

The plan for the day was to have half of it onshore at the abandoned village of Port Leone and half under sail to an anchorage somewhere on Ithaca. (Or Ithaka, as we’re in Greece and should honor Homer and Odysseus.)

Hugh and I made breakfast, which got excellent reviews. He chopped, buttered, and cut, while I cooked. The menu was an omelet with sautéed red onions and red bell pepper, with grated cheese, and toast and jam. It was fun doing it all in a small space with several things happening at once, and everything served (on warm plates) at the same time. I can’t imagine doing it for a living.

After breakfast Dave Bock ferried us ashore in the dinghy. The beach was rocks and trash. There was some trash inland too, but not enough to detract from the mysterious appeal of ruin and abandonment.

A paved road ran as a brown thread down the shore to a distant village visible by its terracotta roof tiles. The road was in surprisingly good shape. We were told that women come out every month to keep the church presentable. A late-model Land Cruiser-like vehicle was parked near it.

Up hill from the road were tumbledown terraces with olive trees and walls of buildings. The church had been painted in the last decade for certain. It was locked, as were the doors of two buildings next to it, one a residence, the other a small tower.

Two flags hung limp on poles on a terrace looking out on the water. One was the Greek flag, shredded to ribbons that were tied in a Gordian knot. The other was yellow and had simply wrapped around itself into an unflyable state. I explored the area alone and then later with Brian and Sasha. Brian unwrapped the yellow flag; it had a double-headed eagle on it. Was it Russian? It flapped in the wind.

Below the church there was what looked like a public building, also intact and locked up, and three piers of concrete and wood. To one side was a roofless ruin with a rusted vertical screw and tun, which someone had read in the cruising book had been an olive press.

There were a few words of graffiti on the stone and stucco buildings, but not many. Clearly lots of people came out here—there were campfire scars—but it was largely an unruined ruined town.

A point of land on one side of the cove had the two ruins of stone towers. We all headed out there on a goat trail but Brian, Dave, Sasha, and I turned back, as it seemed too much work. We returned to the dinghy to row to the point instead. Just as we were shoving off Emma and Hugh appeared; they’d turned back, too. So, we all piled into the dinghy and rowed out to the sailboat.

After an unsuccessful effort to pick up the electric outboard—nobody, including Nick, could get it running—we left Dave and paddled to look at the ruined towers. Each had about 30-degrees of the original stone cylinder still standing, and each had the remains of circular steps and windows at the top. It was hard to tell if the top was the original top, or if something had been above it.

What were windmills doing out here? Clearly not making electricity, and unlikely to be moving water. We concluded they drove olive presses. There were remnant walls that might have been buildings, and olive trees on the slope above the point. We wondered what it must have looked like a half-millennium ago, with people carrying baskets of olives down the hill, and shuttling casks and crocks of oil to the village in boats.

We got back to the sailboat and weighed anchor just as another boat arrived. I was glad we’d been alone, and I’m sure they were happy to see us leave.

We sailed south and went past Atoka Island, which has dramatic cliffs of sedimentary rock that had been uplifted at a slant. We’re going back to explore there tomorrow.

The route to Ithaka was one long close reach. I handled the sheets a few times but had no time on the wheel. I meditated in a supine position on the foredeck and practiced cleating and knot tying in the stern.

We looked at two anchorages on the northeast end of the island before finding a beautiful one more to the south. It’s in a broad bay and we are the only boat in it. As I’m writing a full moon has risen over the cuprous sea.

Saturday, May 6

We woke in a cove out of a sailing magazine or travel brochure, and didn’t want to leave soon. A shore party of most of us headed to the island of Pera Pigadhi to find a trail to a spring, which was visible on Google maps but wasn’t mentioned in the 2017 cruising guide we are using.

It was sunny and beautiful. Brian, who is an open water swimmer, swam to our landfall about 400 yards from the boat. He had no wetsuit but did have a neoprene cap. He shivered for 10 minutes after we got to shore and delivered his clothes to him.

The trail to the spring went up a stream in a cleft in the mountain. We started there and then left it in favor of a path on which we saw white and blue blazes, Greece’s national colors. We walked about 15 minutes to a junction that Nick arrived at first. He went down to the spring, which he reported was surrounded by a steel fence and not much to see. So the group decided to proceed farther up the trail without visiting it.

We walked another 20 minutes, gaining height and better views of our boat below every time we had an unobstructed view. And, of course, great views of our little patch of the Ionian Sea. It was sunny and warm, especially with our exertion.

Dave Bock, Emma, and Brian swam back to the boat while the rest of us paddled or traveled as passengers in the dinghy, which unlike the sailboat is a pathetically designed and inadequate-to-the-task craft.

Dave the instructor had stayed behind to prepare breakfast. It wasn’t quite ready when we got back; he was awaiting our return. Everyone who hadn’t swum, and some who had (except Hugh) changed into bathing suits and dove into the gin-clear water. I did this too–the last in, but not wanting to be the hypothermia-fearing hold-out. I wore my neoprene vest, silicone cap, and of course my prescription goggles.

It was less cold than I expected. It was wonderful, in fact.

Just before I went in, some of the people drying off on the starboard deck saw in the water next the boat a long and occasionally moving thing.

There as a debate about what it was; it looked a little like a sea snake, but it had a spade tail, so wasn’t that. Someone thought it was an anemone. It appeared to have a mouth and I said with a straight face that it was a “Mediterranean pencil moray.” Everyone stopped talking for a few seconds and looked at me with semi-believing faces. I relieved them of this.

We later learned it was a siphonophore—scientific name Farskalia edwardsi—and in fact a colony of more than one organism. The more amazing thing, however, was that when viewed underwater (which I did) its body became transparent except for a white line down the body–a gut or spinal cord. Its shape was represented by hundreds of tiny tentacles (or so they appeared) anchored to the body by brown feet. It looked, floating in the water column, like a constellation of unconnected stars, unlike anything I’d ever seen.

We had a great breakfast, far from NOLS’s infamous 1965 winter-camping cuisine. We had sweet potatoes and bell peppers sautéed and softened, with fried eggs (their topsides steam-cooked from a cover over the pan), with melon slices on the side. It was unfancy, fat and starch-rich, and delicious.

We set sail without reluctance, as our destination was Atoko Island, which we’d passed on the way down the previous day. It’s nearly uninhabited, high, with dramatic cliffs of uplifted and deformed limestone from the Jurassic era.

We motor-sailed there, as the wind was light and we wanted to have time to explore.

We got a closer look as we approached the island. Layers of sedimentary rock a foot thick were bent like parallel curves on a high-school algebra graph. The stone had been plastic at some point, or more likely the force that moved the ancient seabed was so strong it had made the stone plastic.

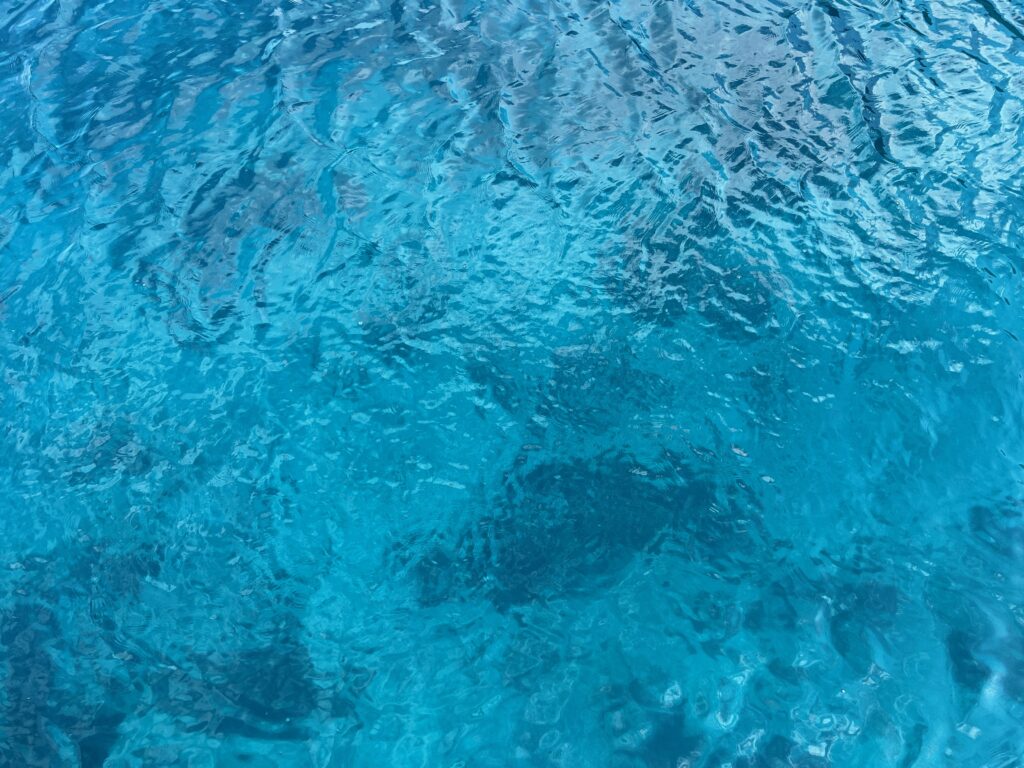

Sasha and I swam into a rock beach. About fifty yards offshore the bottom turned to rocks tumbled smooth by millions of years of tides. Interspersed among the white stones were ones brindled red and brown, perhaps one percent of the shoreward bottom. The water was both perfectly clear and intensely blue, a mysterious trick.

Once on the beach it was possible to see how beautiful flat, white, ovoid stones can be. It was also a lesson that random friction’s target shape isn’t the circle but the ellipse (although there were a few near-perfect circles; I picked one to keep.)

A section of the cliff on the beach was a fascinating geology lesson—if only I’d studied geology. Studded through the rock at regular intervals—never touching—were round, grapefruit-size pieces of brown stone. Some had lost their weathered surfaces and revealed a shiny grainless interior that looked like flint. How the inclusions came to inhabit the limestone like raisins in a Christmas pudding is another mystery of the place.

We swam up the beach and around some rocks to a tiny cave, where another deposit of stones was high but not dry. I was curious whether they were more nearly perfect than the ones exposed on the beach, but they weren’t. It was in such a place on the California-Oregon border that I found two beautiful elliptical stones when walking with my beautiful friend Charlotte, and later wrote “Two Stones.”

Wind was light in the afternoon as we headed to Kioni, a town north of the hourglass waist of Ithaka. The instructors turned the boat over to us. We raised the anchor, motored out into the open water, raised the sails, shut down the engine, and sailed a course to our destination.

We were on a close reach much of the way. I got helm time. We practiced sailing in circles—off the wind to a jibe, then up the wind to close-haul. When three of us had done that and the last person had taken us into the anchorage, Nick took over the helm. It was about 6 o’clock.

I won’t go through the details except to say we spent nearly two hours securing the boat for the night. The boat’s stern was tied with two lines to hooks and loops of rebar fixed to the rock, the bow at anchor. One of several problems was that the anchor refused to hold, until it finally did. On a road along the shore high above us people watched, got bored, and walked off, and new people arrived. A few stopped to watch us on the way to dinner in the village and stopped to watch us on the way back home.

Kioni has three ruined stone cylindrical buildings in a line on a point of land that forms one half of the entrance to the harbor. They were windmills for grinding grain (vintage unknown) we were later told.

The cruising guide said that Kioni once had 2,000 residents but now only 200, as there’d been a big migration to Australia and America. It seems unlikely there are so few inhabitants today, but I’m sure many of the houses are occupied by seasonal visitors.

The village is on a series of terraces on the hillside. The houses are two-storey white stucco with two-over-two windows. The shutters are red, blue, and a few black. Most were closed.

Sunday, May 7

So what to say today?

We all started out on an upstairs, view-of-the-harbor café in Kioni. After ordering breakfast but before it arrived I walked around. The streets were steep and I only went up two of the terraces. I passed an elementary school that had a tidy new schoolroom and a tired basketball court next to it. How far Springfield, Massachusetts’s invention has traveled!

There are burned-out hulks for sale for 200,000 euro; if you want something habitable it will cost at least 700,000. It’s a beautiful little village—a great place to spend the winter writing a book. In another life.

We reprovisioned, returned to the boat, and headed out.

We sailed upwind until we came to a cove in Arkoudi, an uninhabited island. I went below and finished the account of yesterday and also wrote a message and sent photographs to John Mosser, my cousin, who is about to die in Colorado. Most everyone else, led by Brian, the frigidmeister, went swimming. It was very cold, they said.

We had lunch—we do lot of eating on NOLS alumni cruises—and headed off. We’d once hoped to get to Assos, on the outside shore of Kefalonia, but it wouldn’t happen today.

Instead, we learned about the “favored tack”—the tack that will get us to a destination, which now was Fiskardho, a bigger and fancier place than our last few stops.

Houses were under construction on the starboard shore as we headed into the harbor. There was also the remains of what the cruising book said was a “Venetian lighthouse.” There were many other boats; we tied up to two trees stern-to-shore in line with six others.

Hugh and I made dinner—pasta with tomato sauce. The boat has no herbs and spices, and I had to save our two onions for the cooks who wanted them for our last dinner. This left us with a reduced flavor pallette (and possibly palate, as well). We constructed the sauce from sautéed garlic and carrots, and red wine (which I consumed too much of while cooking) in addition to the tomato sauce. Grated cheese was offered at the table. It turned out better than expected.

While I was cooking other members of the crew rigged the dinghy up to one of the mooring lines as a hand-driven ferry. After dinner we took it to shore and walked around the town. I finally found a place with a chart, which I bought for 22 euros. We then turned around and walked out a path to the old lighthouse.

It was dark and we all sat on the rocks when we got to the lighthouse. We waited for the moon to rise over a hill across the harbor. The sky took on a yellow glow before the bright edge appeared.

We were on Ithaca, and as the moon came into full view I read “Ithaka” by Greek poet C. P. Cavafy.

As you set out for Ithaka

hope your road is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians, Cyclops,

wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

Hope your road is a long one.

May there be many summer mornings when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you enter harbors you’re seeing for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfume of every kind—

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to learn and go on learning from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for.

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you’re old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her you wouldn’t have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

I’d warned the group early in the trip this might happen. They didn’t seem to mind.

My cousin John Mosser sailed around the world in 1976 with four college friends in a leaky 50-foot wooden boat. Their technology was closer to Captain Cook’s than to ours. His courage and expertise, which I admired for decades, was one of the things that made me want to learn to sail.

I sent him this poem about a long journey and its impending end. It arrived the day the died. He didn’t see it, and I think that’s best.

Monday, May 8

I got the first mosquito bites of the season last night. We were anchored along a stretch of woods, which was probably the reason.

We’ve eaten out more than most NOLS alumni trips and more than I expected. Nick has been nice about picking up checks and refusing contributions from the crew. But we’re also about using the food we have on board and wasting as little as possible, so this morning Hugh and I made french toast, grizzled ham, and orange juice, working through our stores. We had no vanilla and of course no maple syrup, but I made a syrup of melted butter and honey, and we had apricot and peach jam.

We motored out past the Venetian lighthouse. On closer inspection we saw portholes in the stone-and-stucco tower at different heights and points of the compass. Dave the instructor said that he thinks it worked this way: fires were lit at every porthole; the light from each was visible only from certain positions at sea, providing directional signal.

The crew has been lobbying for a while to go on the “outside”—the open-Ionian side of the islands. The charter company doesn’t let its customers spend the night in anchorages out there. We’d originally wanted to go to Assos, on the western shore of Kefalonia, but it’s been obvious for a couple of days that it was too far for a lunch stop. So instead we set a course for the west side of Levkas, the island north of Kefalonia and Ithaka.

We motor-sailed most of the way, as the wind was light, passing an unlit lighthouse that looked to be from the late 19th century (Ak Dhoukato, according to the chart). Beyond it were spectacular cliffs, white with rusty veils that had dripped down from above.

We dropped anchor and had our late-morning snack. I’m trying to get rid of my gorp, so I brought out a bowl, which was mostly consumed. Our mid-afternoon snack—we eat almost continually in NOLS Alumni World—finished it off.

The sun wasn’t out, but it was a beautiful place that invited swimming. Around a point, which we’d looked at and rejected, was a beach with umbrellas dotted along it and people strolling. We retreated from them and anchored the boat.

There was a small beach and a diagonal fissure in the cliff that formed a cave, with two smaller ones next to it. This beckoned, and of course Brian and Sasha took up the challenge. I was determined to take up the challenge as well, but needed time to suit up—neoprene vest, cap, goggles, and willpower. I also didn’t want to swim in alone, as it was about 300 yards, so Emma rowed me. She picked up the other two and they all went off exploring while I stayed and looked around the fissure-cave.

There was an empty water bottle at the far end. Drops of condensation fell from above, and high up a basketball-sized rock was wedged in the crack. The place was protection in a pinch if you were without a boat, but not without hazards.

The water was not as cold as I expected. The bottom was covered with smooth, white ovoid boulders—a Brobdinagian version of the beaches we’d seen.

We were somewhere near Sappho’s Leap, where she supposedly jumped to her death after being spurned by a lover. As if in recognition, a rock fell from the cliff with a great splash, the people who’d stayed on the boat reported when we returned. It seems improbable that we’d be witnesses to erosive forces in real time, but apparently we were. (I didn’t see or hear it.)

In the afternoon we practiced going downwind, which we’d done little of, including sailing wing-on-wing. The wind was brisker than predicted; it peaked at 20 knots, the heaviest of the trip. Nick had us sail blindfolded when we eventually changed course and began to sail upwind. We tacked from close reach to close reach, steering by the sound of the sails, feel of the boat underfoot, and wind on the face. It was a thrilling exercise.

We sailed 34.3 nautical miles today.

We motored to a pocket cove—actually a pocket bight that offered little protection other than the hundred-foot cliffs above it. Dave the instructor and I took the dinghy to the cliff edge where tumbled rocks went down into the water. He tied us to two domed pinnacles while I worked the oars to keep us in place.

These were cliffs one could look at for hours—their bent bands of whorled strata, the baklava and taffy patterns in the rock unexplorable except by eye. High up were a two little caves worthy of New Yorker-cartoon hermits. Swifts, flashing blue wings and yellow bellies, came and went from invisible nests.

Tuesday, May 9

Today is the last day—half-day, actually—of the trip.

We have one thing on the agenda, which required us to get up 30 minutes earlier than usual and eat a quick cold breakfast. On our way back to the charter dock we planned to stop at the big cave on Meganisi that we’d seen on the second day.

It was a windless morning and we never even put up the sails.

We anchored outside the cave, a half-moon of tawny stone disappearing into darkness. I was on the second party to go into it in the dinghy—Dave Bock rowing and Nick and me spectating. How it formed so symmetrically—and with a top 30 feet above the water—is hard to imagine.

Small stalactites sketched a ragged eyebrow over the opening. Deeper in, diagonal threads of raised stone were a variant of stalactites, Dave said. Water dripped from the dome ever so often. The deepest part was not in full darkness and it looked like there was a small stone beach there.

“You could get out of the rain back there, but it wouldn’t be the most comfortable place,” I said.

“I don’t think it has ever seen rain,” Dave said.

We rowed around taking pictures, mostly in silence. No one tested it for an echo. The swifts seemed disturbed by our presence, darting, diving, and giving high-pitched whistles. But perhaps that’s what they would have been doing without us.

As we motored to the harbor we separated the food that could be used by the next trip from the food that would seem second-hand to people expecting a fresh start. We packed up our belongings, piled the towels, sheets, and mattress covers, and coiled the lines so they looked smart—something to inspire the next crew.

The six people coming in tomorrow are a couple, two close friends, and a father and daughter. They are older than this group. It was the trip that I wanted to go on, but there wasn’t room.

I’m glad I got this one; it was a convivial group, not paired-off except for Hugh and Emma, father and daughter, and we had the instructors fresh and enthusiastic. That’s not to say they won’t be that when the others roll in tomorrow—I’m sure they will be—but it was nice to have them before there was something to compare us to.

As we had lunch at a restaurant in Nikiana we talked about how NOLS’s approach to outdoor uncertainties is so different from that of many organizations, and from the American people in general.

NOLS acknowledges risk; there have been 13 deaths since it started in 1965. But uncertainty, hazard, and novel challenges requiring real-time evaluation by leaders and students are not only acceptable, they’re part of the “leadership” NOLS aims to teach.

I asked Nick if he’d be going to new places with the next group, or be heading to the places he now knew would work.

“As always, it depends on the weather and conditions,” he said. “But I’m always interested in seeing things for the first time.”

NOLS is an organization led by people of immense skill and knowledge, and an adventuring spirit that’s cultivated rather than squelched.

I asked about the NOLS scholarship program that’s been soliciting me unsuccessfully for years. It turns out NOLS gives lots of scholarships, some to people it seeks out and some to those who come asking. I may start to give.

We spent the last night back at Villa Diodati. Four of the group walked up from the village—a couple of miles of switchbacks. I needed exercise, but didn’t feel like doing that right after lunch, so later in the afternoon I went up the road from the villa.

About a quarter mile up the road there was a stone track with a stripe of weeds down the middle that went off to the left. I walked up it. Trash, including a toilet and a clothes washer, had been tipped down the slope. Caterpillars descended on invisible threads from branches overhead.

Remnants of squared stone walls and olive trees suggested this was once farmed, and I suppose could still be, although there were no dwellings. Trickles of water flowed among wildflowers and grass that were already tall enough to be falling over. The track disappeared, and soon after, the path. I turned around. The Ionian Sea was visible down the hill and far away.

I walked a mile or so farther up the road, passing a house under construction that will have a spectacular view, and on the uphill side a clearing that had 86 bee hives (all I could see). Two cars passed me; one was a police car.

Nick had ordered another takeout dinner—three salads, gnocchi with beef, grilled vegetables, Greek cannoli and chocolate cake—that was enough for two sailboat crews. The food on this trip couldn’t be more different from what I’d had on the New Zealand sailing class and that I’d lampooned in the travel story I wrote for The Washington Post. (If you’re interested, the story “NOLS for Olds” is in the “Journalism” section of the website.) NOLS has been unusually generous on this trip.

We didn’t have a formal debriefing, which was fine with me. People had made their views known about the experience as it had unfolded, even if they hadn’t declared a best-and worst parts of it.

For myself, I’m glad it occurred to me six months ago to do this, and that I’d said yes to myself. I’m in the yes-or-never stage of life.

I’ve seen a bit of Greece and paid homage, indirectly, to the ideas and history that led to the United States, into which I’m boundlessly lucky to have been born.

The group is dispersing to various places—Hugh to Ireland for work; Sasha to Amsterdam; Dave Bock to Athens; Brian to points in Greece unknown (perhaps to the hilltop monasteries of Meteora); Emma to the United States on a multi-leg trip that will end with her back at work in less than 48 hours. I’m going home, and am glad for that.

It’s too late for me to have the Greece of romance—Lord Byron, Zorba, Joni Mitchell and “Carey.” But I had the Greece of stone, ruins, wind, water, sun, and rain, and that’s good enough.

Recent Comments