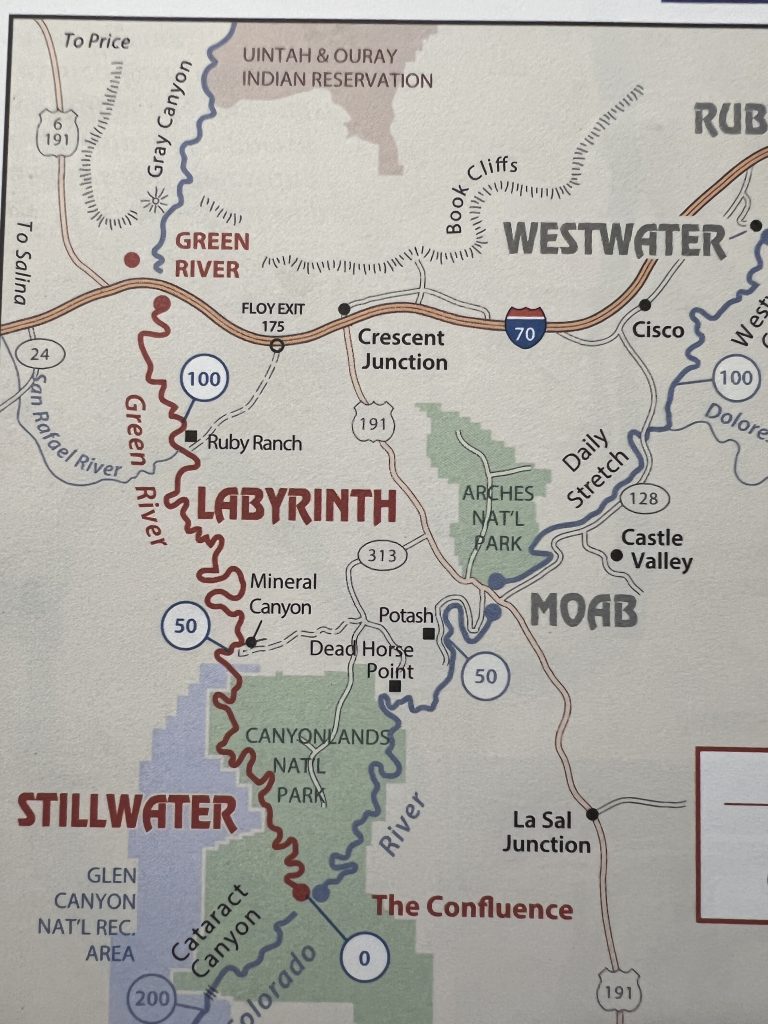

We rented a canoe, paddles, life jackets, and a portable toilet from Tex’s Riverways, an outfitter in Moab, Utah, that’s been in business since 1958. The plan was to paddle through all of Labyrinth and Stillwater canyons, which have no whitewater beyond a few riffles, and thus can be run by non-experts.

In nine days, a jet boat would pick us up a few miles beyond the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers at the last campsite before Cataract Canyon. Cataract has 14 miles of rapids in its 46-mile length; some are Class V, defined as “extremely long, obstructed, or very violent rapids which expose a paddler to added risk.” The jet boat would then take us up the Colorado from the confluence to a takeout from which we’d ride a Tex’s Riverways bus back to Moab.

We left Moab in a van with about 10 other people soon after 9 o’clock in the morning. Half the trip was on gravel roads through rolling desert scrubland.

The put-in was at a place called Ruby Ranch. There there were fenced and irrigated fields nearby and a few buildings visible in the distance. A dozen groups were loading boats–canoes and kayaks–at the the same time we were. Most of the trekkers were about our age (which is never a surprise), although there was one family with children, and three young women on stand-up paddle boards piled high with camping equipment.

Our boat was loaded to the gunwales; its cargo included 18 gallons of water. You can precipitate silt out of river water with alum (a procedure called “flocculation”) and then run it through a filter, but most people carry drinking water if they have room, which we did just barely.

We left a few minutes before noon.

For a while both sides of the river were flat above the fringe of tamarisk, which created an unappealing visual and physical obstruction. In fact, the spindly plant, which can grow more than 30 feet tall, formed a hem between water and rock in all but a few places the entire length of the trip. It’s invasive, of course.

Tamarisk goes back a long time and has always been trouble. In Book 6 of “The Iliad” Homer writes:

. . . But Menelaus lord of the war cry had caught Adrestus alive. Rearing, bolting in terror down the plain his horses snared themselves in tamarisk branches, splintered his curved chariot just at the pole’s tip . . .

Exactly when the plant arrived in the United States is uncertain, but by the 1870s it was being used for erosion control on ranches and, unbelievably, as an ornamental in cities. Its growth became uncontrolled in the second half of the 20th century.

When I went through Desolation Canyon on the Green, and Westwater Canyon on the Colorado, in the early 1980s there wasn’t nearly as much tamarisk as there is now. When Edward Abbey rafted through Labyrinth, Stillwater, and Cataract canyons a few years before that, the river bottoms where his party camped had “jungles of tamarisk [which] does not belong here, has become a pest, a water-loving exotic engaged in the process of driving out the cottonwoods and willows.”

In many stretches of the Green that work is complete. Tamarisk often makes leaving the river and getting to the canyon wall impossible, with sandbars the only place where you can pitch a tent.

As we floated along there soon began to be rock walls and cliffs on one side of the river or the other, but never both. Usually they were on the outside of curves, where the flow is faster; on the inside curves were mud and sandbars.

We passed a few other groups, including four red canoes from our outfitter, and two other canoes rafted up and pulling a white-and-pink inflatable sea monster. The current was almost imperceptible when traveling with it, but strong when going against it, especially in our craft.

We stopped on the left shore for a lunch of leftover pizza from the night before. Larry got out in his muck boots and immediately sunk so deep in the mud he could barely move. Keeping mud out of the boat would become a theme of the trip. So would finding places to camp that were dry and not on the far side of great wallows.

A friend of Larry’s who’d done this trip several times had given him a list of possible camping spots. By mid-afternoon we were starting to look for one. We rejected a site that would have required carrying our stuff 30 vertical feet up a bank to a sandy clearing. We eventually found one on an island off a red-rock bowl on the right bank.

The sand was flat and dry, and there was enough driftwood for a small fire on our fire pan, which was the size of a trashcan lid. Fires on sand or rock are prohibited.

We heard animal noises that night. Larry wasn’t sure what they were, but I think they were from beavers. I’d seen branches with telltale gnaw marks when I’d gone looking for wood.

Recent Comments