Today I’m going to visit the grave of my ancestor John Brown.

My parents visited the grave 50 years ago. My sister, Ellen, and my second cousin, Michela Nonis, also visited it when they were 16 years old and traveled alone through the British Isles. (What a different world we live in today!)

I’m interested in history, and family history, and I want to see this grave before I’m in one myself.

So who was John Brown?

For starters, he’s not from the Brown side of my family, although he’s certainly from the Brown side of many Brown families. He’s an ancestor of my mother, Sally Jane Mosser, whose mother was Dorothy McCormick—whence the Scottish lineage.

When an ancestor is a martyr it’s tempting to think of him or her as a reasonable person, or at least someone committed to a laudable creed. I have no idea how reasonable John Brown was, but his religion was an unappealing one.

At the time of his death, Scotland was a “nation governed by a harshly repressive Kirk [church bureaucracy]; a nation of unforgiving and sometimes cruel Calvinist religious faith; of trials for blasphemy and witchcraft; of a cranky, even perverse contrariness in the face of an appeal to mercy or reason or even the facts,” wrote historian Arthur Herman in “How the Scots Invented the Modern World” (2001).

The restoration of the Stuart line after the Cromwell interregnum threatened this world.

The British monarchy had resumed its efforts to control worship, and in particular to force people to attend Anglican services. The people who refused were known as “Covenanters.”

The name came from a document that circulated for signatures in 1638.

“The National Covenant was more than just a petition or declaration of faith,” Herman wrote in his book. “It was the Presbyterian version of democracy in action. In the name of true religion, it challenged the king’s prerogative to make law without consent, and affirmed that the Scottish people would oppose many change not approved by a free General Assembly and Parliament.”

By a half-century after the Covenant was written, however, many Scots were tired of chaos. They submitted to the British monarch’s required worship.

“The new church was greatly detested, both as superstitious and foreign; as tainted with the corruptions of Rome, and as a mark of the predominance of England,” wrote the author of a genealogy called “Matthew Brown,” a leather-bound book published in 1900 that meticulously (and, for me, thankfully) describes the direct descendants of one grandchild of John Brown the Martyr.

“Disastrous wars and alien domination had tamed the spirits of the people, and there was no general insurrection, and a majority of the people, with many misgivings of conscience, attended the ministrations of Episcopal clergy,” the author wrote.

But not John Brown.

He and fellow dissenters gathered in isolated places, often outdoors, to worship. They brought edged weapons, and sometimes guns. The practice was most prevalent in the western lowlands, south of Glasgow. Priesthill–an ironic name for the place where Brown’s hovel stood–was in the middle of Covenanter country.

“Hunted down like wild beasts, tortured, imprisoned by the hundreds, hanged by the scores, exposed at one time to the license of the English soldiers, abandoned at another time to the mercy of bands of marauders from the highlands, they still stood at bay in a mood so savage that the boldest and mightiest oppressor could not but dread the audacity of their despair,” wrote the genealogist.

(That’s compelling writing for an obscure author, whose name was Robert Shannon. ” Audacity of despair”–that’s even more memorable than “audacity of hope.”)

The persecution was so great that John Brown had to give up his occupation as a carrier and intermittently go into hiding.

He was cutting peat at his holding when English troops came for him on the morning of May 1, 1685. Their leader was John Graham of Claverhouse, who later became a Jacobite hero, killed at 41 in the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689. To Covenanters, however, he was–and still is–a merciless enforcer. He’s the Klaus Barbie of what was known as the “Killing Times.”

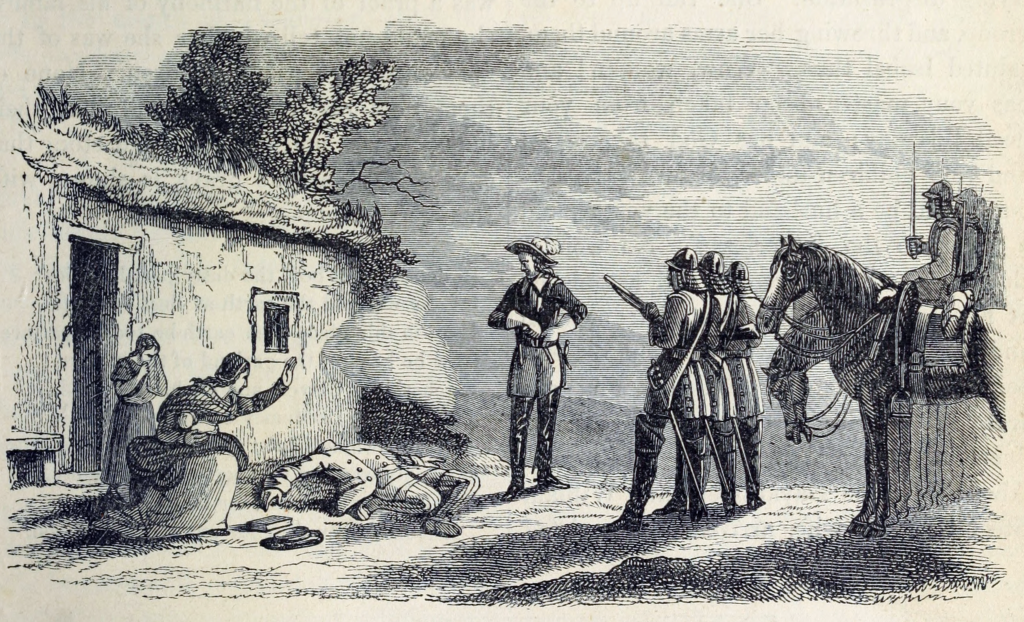

This is a depiction of Brown’s death from the book “The Scots Worthies” (1844).

A more dramatic rendering is entitled “The Martyrdom of John Brown of Priesthill, 1685,]” by Thomas Duncan (1807–1845).

When Brown was killed his household consisted of his wife, Isabel Wier; a seven-year-old daughter, Janet, whose mother was Brown’s previous wife; and a two-year-old son, John. Isabel was pregnant with a boy, James, born later that year. Brown was 58; his wife’s age is unknown, but she was certainly younger.

How long she and her children stayed in Scotland is unknown. What’s certain is that a decade after John Brown’s death, life in Scotland became even more difficult.

Starting in 1697, the country had three harvest failures in a row. Tens of thousands of people died in what became known as the Lean Years, which ended in 1703. “For an already impoverished and sparsely populated country of fewer than two million souls, the 1690s set a benchmark of collective misery and misfortune Scots never approached again,” the historian Herman wrote.

Brown’s survivors eventually immigrated to the “Province of Ulster” in Ireland, which is now Northern Ireland. It’s believed that Isabel remarried, but if she had more children they’re lost to history.

Her sons James and John, with their families and some friends, immigrated to America in 1720. (John’s wife delivered twins at sea.) They settled in Pennsylvania about 10 miles southeast of present-day Harrisburg on Swatara Creek, a tributary of the Susquehanna River.

John, the older brother, had seven sons and no daughters, and James, the younger, had six sons and no daughters. This is one of many reasons why Brown is such a common name in America.

Whether my father’s Brown ancestors, who emigrated from England much later, have kinship with this line of Browns seems doubtful. But I haven’t investigated.

What’s certain is that my mother, Sally Jane Mosser (later Brown), is descended from John Brown in two ways. Her mother, Dorothy McCormick (later Mosser), was descended from the Martyr through both her mother and father.

Dorothy’s mother was descended from Jean Brown, one of John Brown’s great-granddaughters. Her father was descended from Mary Brown, Jean’s older sister and also a great-granddaughter of the martyr.

(Dorothy’s parents had John Brown as a direct common ancestor, but technically they weren’t in a “consanguineous” marriage. That requires a second-cousin or closer relationship of the husband and wife, which they didn’t have.)

What’s interesting is that the descent of John Brown’s “blood” took three generations to reach Dorothy through her father’s line, but only two generations through her mother’s. It took three generations for Mary Brown’s descendants, but only two generations for Jean’s, to reach the 1850s—which is when Dorothy’s parents were born.

The reason is that in the maternal line the blood link was carried by children born near the bottom of the birth order in large families, while the paternal line descent was carried by people born at the top or middle of the birth order. The paternal-line descendants started farther back in time; it took an extra generation for them to get to the 1850s.

To be precise (non-family can skip this paragraph) Jean Brown’s descendants of my grandmother were from the later-born of several generations. Jean was the 5th of 8 children, her daughter Martha 11th of 12, and her daughter 7th of 10. In contrast, Mary Brown–Jean’s sister–was 2nd of 8; her daughter Hannah was 1st of 10; her son was 4th of 6, and his son was 5th of 8.

One of Jean Brown’s granddaughters was Margaretta Hill, born in 1854. One of Mary’s great-grandsons was Horace Greeley McCormick, born in 1850. They married and were my maternal grandmother’s—Dorothy’s—parents.

Like most married couples, they were roughly the same age. But in their case they were genealogically a generation apart when it came to one particular ancestor—John Brown.

This out-of-sync descent blood yields an unusual result.

The Martyr is both my great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather (“sixth great-grandfather,” as Henry Louis Gates, Jr., would say) and my great-great-great-great-great-great-great grandfather (“seventh great-grandfather”). You might ask, how can that be? If you chart a family tree, it’s just what happens.

John Brown the Martyr may stand out in my family history, but he’s only a face in the crowd. I—and you—have 256 sixth great-grandparents, and 512 seventh great-grandparents. That’s so many it’s hard to think of them as relatives. But they are.

Tomorrow I’m going to stand over the bones of one.

The illustration and painting are riveting — such emotion in the painting. And impressive genealogical research!