On the cab ride back to Cumnock from Priesthill Farm, where I’d visited John Brown’s grave, the driver pulled off the road.

”You see to the left of the telegraph pole, way out there?” he said, pointing out the window. “There’s another one.”

I could barely make out an obelisk with a conical top. It rose out of a rectangular enclosure, much like the monument at John Brown’s grave.

The Airds Moss Covenanter Memorial, which he was pointing to, marks where 112 English troops and about 60 Covenanters encountered each other on July 22, 1680. (The place name denotes a kind of bog.) Twenty-eight soldiers and nine Covenanters were killed, including their leader, the Reverend Richard Cameron. Five wounded Covenanters were taken to Edinburgh and hanged. Cameron’s head and hands were cut off and shown to his father, who was in prison there, and then publicly displayed.

Cameron’s fighting spirit was much admired. A regiment of Scottish infantry called the Cameronians was formed. It fought around the world for the next 279 years until it was disbanded in 1968.

The Covenanters are still heroes here. There are dozens of monuments to them. Many are more than two centuries old, tended by the Scottish Covenanter Memorials Association, established in 1966 three centuries after the fact.

Why?

Covenanter memorialization isn’t big business and there can’t be many Covenanter tourists (although I suppose I’m one). Local pride counts for some of it. But the bigger reason, I believe, is that people realize they represent something worth remembering.

The Covenanters bear a resemblance to the maquis, or French Resistance fighters, and the Italian partisans of World War II, although they were not nearly as violent. They were a living, voluntary statement that not everybody will go along with the demands of an occupying force.

True believers that they were, they kept up their opposition for more than two decades. Hundreds of people died in what was known as “the Killing Time,” roughly 1667 to 1688. John Brown was just one of the better-known victims.

The English army routinely executed without judicial proceeding Covenanters taken as prisoners in armed encounters. Most killings, however, were for religious and political crimes, including worshipping in secret “conventicles” or refusing to swear that the king was head of the church.

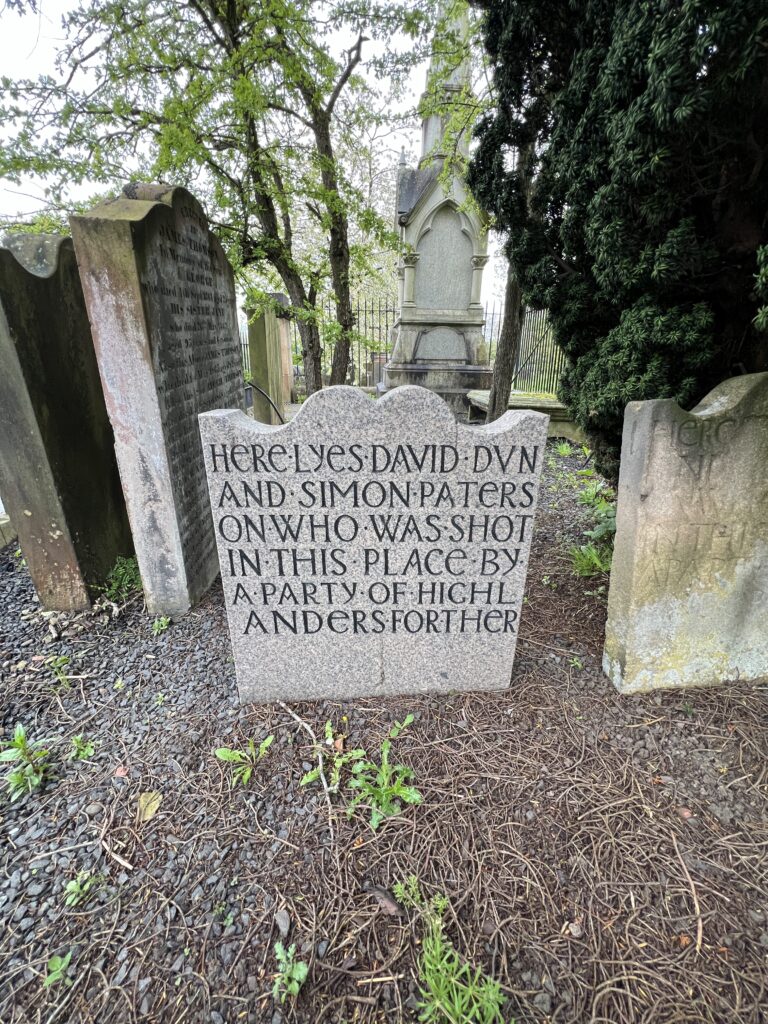

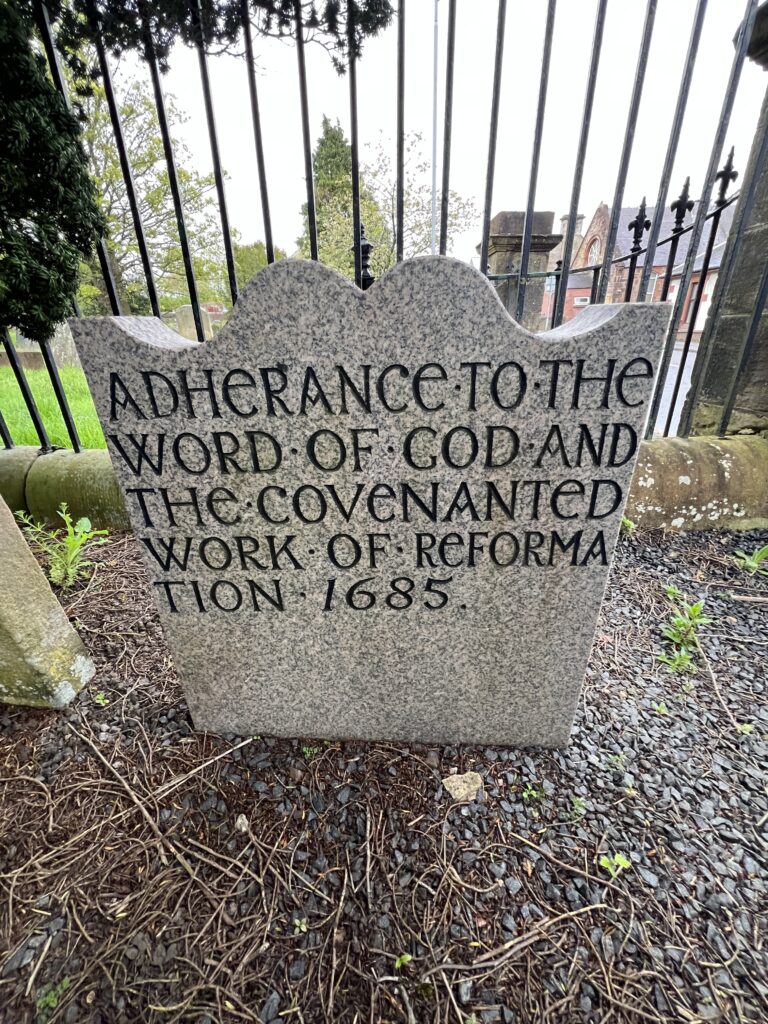

In the spring of 1685, two men, David Dun and Simon Paterson, were arrested by Highland troops in the employ of the English as they were returning from a conventicle. They were taken to Cumnock (where I’m staying), and shot. When Dun’s sister, Margaret, came to town to inquire after her brother she was shot, too. Nearby, in coastal Wigtown, two women (one a teenager) refused to swear religious allegiance to the king. They were taken to a cove at low tide, tied to stakes and left to drown as the water came in.

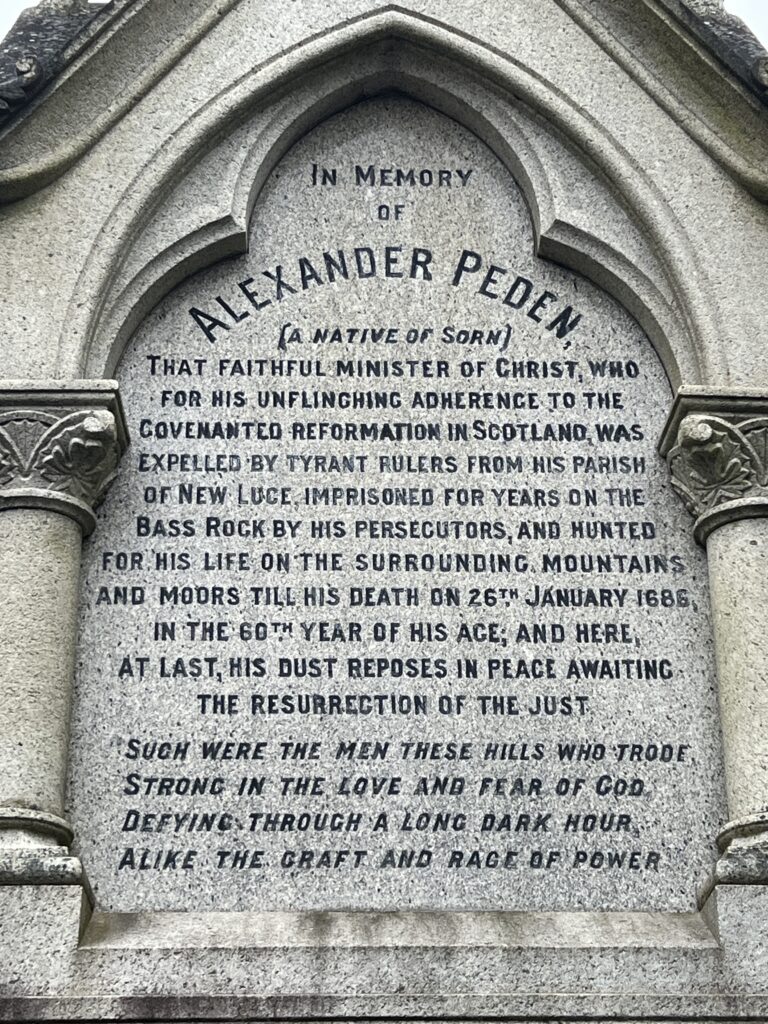

Alexander Peden, who performed the marriage of John Brown and his second wife (and predicted his martyrdom at the wedding), was the movement’s Mandela-like figure.

He spent time in exile in the Netherlands. He was imprisoned for four years on Bass Rock, Scotland’s Robben Island off the east coast. In 1678, he and 60 followers were sentenced to banishment to the “American plantations.” When the American captain of the ship that would carry them learned their crimes were religious he refused to take them aboard. Peden escaped to Ireland.

In 1686, six weeks after Peden died (of natural causes) back home in Ayrshire, a “troop of dragoons” exhumed his body and brought it to Cumnock. They planned to display it on the village’s gallows, but were dissuaded. They reburied it there instead, which was itself an insult. The Cumnockers responded by turning Gallows Hill into the village graveyard, making it hallowed ground.

And then in 1688, William of Orange, a Dutch Protestant, became king of England and Scotland. Two years later, Scottish Presbyterianism was accepted by the Act of Settlement. The Covenanters had won.

I walked around the Cumnock graveyard the morning after I visited the John Brown monument and before I took the train back to Glasgow.

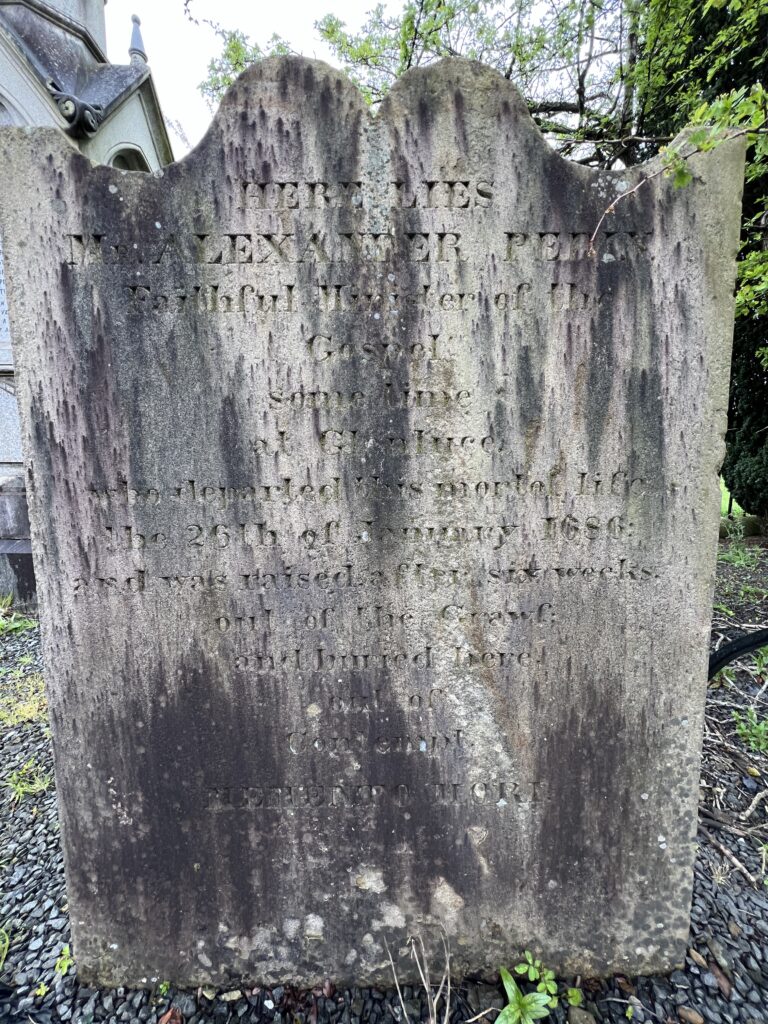

Here is Alexander Peden’s gravestone, and a monument to him.

And the shared grave of David Dun and Simon Paterson—obviously a recent replacement for one no longer legible. Remember them!

The Covenanters were not tolerant people. Like the Puritans, they were religious fanatics. The Puritans were so intolerant that in 1690 they hanged one of their own, Mary Dyer, when she converted to Quakerism and refused banishment from the Bay Colony. Her statue stands in front of the State House in Boston, a permanent reminder of shame.

Like the Puritans, the Covenanters had an armature on which a new, more tolerant society could be sculpted once religion had been stripped away.

That society has become America.

The tens of thousands of Scots-Irish immigrants to colonial America (and their millions of desendants) have an even better claim on being the progenitors of American democracy than the Puritans.

They resisted authoritarian rule. They refused to swear oaths of allegiance. They died (and occasionally fought) for self-rule in both church and civil matters. They had common dedication to principles. They eschewed elitism and hierarchy more than most people of their time. As the Alexander Peden monument says, they resisted “the graft and rage of power.”

In seeking freedom from several forms of oppression, they paved a way for the enshrinement of several forms of liberty beyond that of religion (thank you, Thomas Jefferson), although obviously not enough (see: Jefferson, above).

In important ways, the Covenanters’ personality and principles have bred true to the American present.

Recent Comments