As noted, I picked this year’s route because I thought there was a good chance of meeting people along it. I have not been disappointed.

One’s reaction to chance encounters is usually “not enough” rather than “too much.” Of course, how could it be otherwise? Too much, then just walk on.

One also realizes there’s a big world out there in purpose and direction, not just identity and timing.

The first person I met on the trail was Hugh from Leicester. He’d done two or three crossings, was serious but not obsessed, fast. I wanted to know more of his story but I haven’t seen him since the morning after the first night when he was packing up beside the sea loch. I hope I see him again.

The next person I encountered was Mikhail. He was going in the opposite direction from me, so unlikely to be a Challenger. It turns out he’s Polish and headed to Cape Wrath, most northwest point in Scotland. Could there be a better named place?

There is no no single route to Cape Wrath, only headings. Mikhail was not going the whole way. He planned to get off the train closer to the coast but got impatient. He got off at Ft. William.

”I just decided to come on this way,” he said. He’s going to be out six days, no time to waste.(So much for meticulous route planning, which is the way of the Challenge.)

“It is so beautiful here,” he said in barely accented English. “We don’t have this at home.”

Not long after, I ran into two more men heading in the opposite direction from me. I was surprised to see that one of them was barefoot. He’s Roy, an Israeli. The other man is from France; I didn’t catch his name.

Roy said he was tired in walking in wet feet. You can see how small a “kit” ( as they call it here) he has. You can hardly see his backpack. He’s never been to the United States, but is coming next year to hike the Pacific Crest Trail—Canada to Mexico down the West Coast.

Roy plans to make Cape Wrath in 10 days, the Frenchman in 14. A chance encounter, they’ve been walking together for 36 hours, but will soon part ways.

Farther along, I met Jessica from Amsterdam. She said she’d just finished bathing in a pool of frigid, tannin-stained water in a stream the path crossed. She had a Garmin beacon like the one I’d bought. We agreed the instruction manual, in six languages, was no help, although she’d managed to figure out more than I (no surprise).

That night I had three fishermen as neighbors at the east end of Loch Arkaig. I was over a hump in the shoreline; I don’t think they even knew I was there. Their camp included an elaborately protected privy. This man was heading to it as I left.

This was the day I left the road and went up the hillside to get a cell signal so I could order a replacement keyboard from Apple.

(It’s arrived, but I can’t connect it despite following the directions, which are in seven languages. It’s a “magic keyboard”; all I wanted was one that worked. This is a disappointment but not a surprise; see “waterproof” boots in a previous post).

After a tiring day—the hillside was trackless and I had to walk along the fall line of the slope—I got to a forest road and started to look for a place to camp. I didn’t find one, but I did find a bird-watching blind the forestry company had put up. There was a nice view, but no eagles.

I proceeded downhill to the lakeside, hoping to find an acceptably private stretch of shore. They were hard to find. I eventually rounded a corner and saw a tent on a patch of grass next to a rocky foreshore. Beyond it was a small peninsula that might have dry ground. A man and woman were sitting outside the tent.

“Would you mind if I looked for a pitch out there?” I asked.

“You on the Challenge?” the man asked. I nodded. He gave me a thumbs-up sign. “There’s room right here.”

The right here was right next to their tent. I hoped they weren’t on their honeymoon. I protested, then thanked them, then stepped off the road onto the patch of grass, and heaved off my pack.

He was Graeme Dunshire, on his 16th crossing. The woman was Liz, his longtime companion, whose last name I don’t know. She’s accompanying him for a week, not the whole Challenge, as she has commitments at home,

I was appreciative of their generous gift to me of their privacy. Before bed I gave them a bag of homemade gorp—quite tasty and famous among my outing friends—of which I had an extra.

Graeme and Liz turned out to delightful and helpful travel companions, even though we didn’t travel together. Graeme is a builder and joiner; he told me to look out for house he’d worked on that I’d pass that morning. I don’t know what Liz does.

The next morning they headed off before me. Soon after I started I met a man named Tim, also on the Challenge. We got into deep conversation and eventually got a bridge and waterfall that seemed like a good place to stop.

Graeme and Liz were there. Graeme graciously pointed out we’d missed a turn a while back that was going to take us on our route, which was different from theirs.

Tim and I turned around and got back on the right route. We walked and talked. It was a nice morning, intermittently sunny with no rain in the air.

I’d seen the designation for a museum coming up on the map and mentioned I’d like to stop. Tim was game , but more interested in coffee and ice cream, which he’d been told was on offer.

We got there before it opened and sat at a picnic table. Soon a car with two people appeared. Soon after so did Graeme and Liz, from a different way About 10 minutes before the official opening time a young man came out and said we could come in.

I thought the topic was going to be about commando and other World War 2 training that had taken place on the estate, but it turned out it was the museum of the Clan Cameron, whose home grounds we were on.

The Camerons have a complicated history I only vaguely understand. They were mortal enemies of a couple of other Highland clans, and supporters of the Catholic Stuarts and their attempt to reclaim the English and Scottish thrones in the person of Bonnie Prince Charlie. They struck me a bit like the Indians who fought on the side of the French in the French and Indian War.

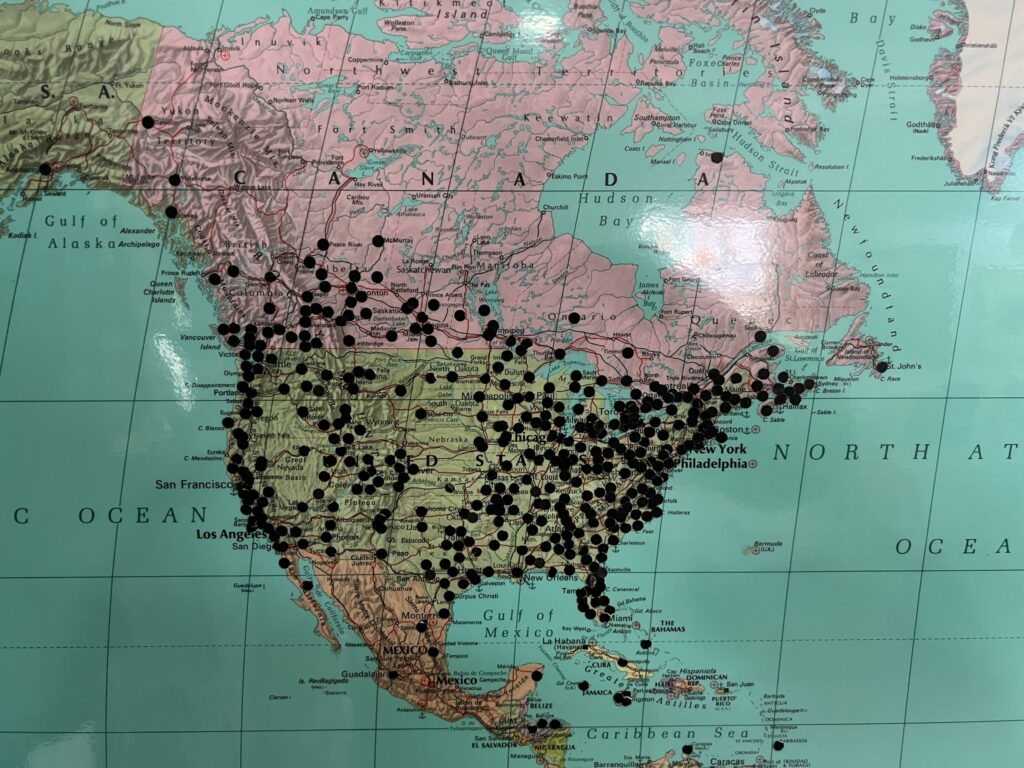

The prince’s invasion and uprising failed, but that wasn’t the end of the clan. It spurred emigration and there are now millions of Camerons around the world. The museum is a bit of a Mecca for them. Here’s a map of the homes of Cameron-blooded visitors to it; they’re the black pins.

The commonness of Scottish ancestry in the U.S. and Canada is evident.

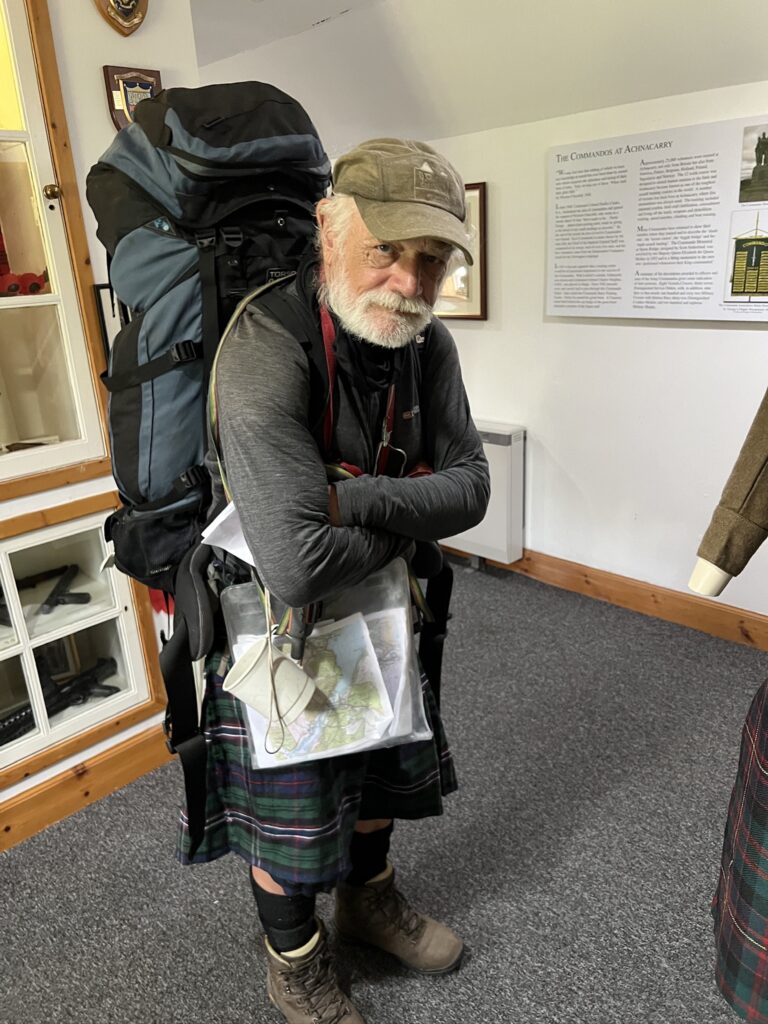

One of the visitors was another Challenger who looked like he’d stepped out of one of the paintings. (You’re hard core when you don’t even take off your pack.)

We all had some snacks and headed off in different directions.

Amazingly, a couple of days later I was coming down off a ridge to Loch Ossian. I saw two people heading toward me at a place where several trails converged.

They crossed a small bridge.

It was Graeme and Liz again, heading on a different route, but still eastward, of course.

Some people surprise you on the trail. I walked around a corner in a forest track and came across “the wee minister.”

A sign said a previous sculpture in metal had been destroyed in the 1970s. (No mention whether it had been an an act of God or man.) This was the replacement. I put all the coins in my pocket in his collection box. It’s supposed to be good luck.

There are fleeting companions. I thought I was in the middle of nowhere

when I heard a distant rumbling and in a few minutes this came by.

There are some companions you never see. I got to the foot of Loch Treig about 7 o’clock and really wanted to stop. It was drizzling. I looked around for a water source but couldn’t find one other than the loch, which required going across a swampy shore.

The person in the tent at the extreme left might have had an idea. But nobody came out as I walked around, and I didn’t want to disturb them, so I walked on.

There are people who you’d like to get to know better, like these guys taking a smoke break outside the village shop in Kinloch Ranoch.

The most memorable companions, however, are those with whom you share distilled accounts of important experiences and history.

Tim and started out with small talk about routes and equipment, as is often the case. His pack was on the bigger side of the bell curve, but nothing like mine. I asked how much it weighed. He didn’t know.

“I fill it with what I need and that’s the last I think about it,” he said.

We talked about tents, and the trade off between a light one and a comfortable one. He has a Hileberg, as do I—a Swedish beauty that used to be considered light but, comparatively, is no longer. He bought his in the 1980s with the 50-pound inheritance his father, a coal miner in Nottingham, had left him.

Tim’s father was one of “Bevin’s Boys,” named after Ernest Bevin, who was Minister of Labour and National Service during World War 2. They were young men persuaded (and some eventually conscripted) to go into the mines when Britain’s coal production lagged. He worked there for more than 40 years.

Tim went on a school field trip down into a mine when he was 15. He couldn’t imagine working there. Instead, he worked at the post office for more than 30 years before retiring a few years ago. He now does part-time maintenance and ushering at Albert Hall in Nottingham, and hospitality for the city’s football club.

Tim grew up in council housing and knew nothing about camping or hillwalking as a child. But he knew he wanted to see Scotland, so he took a trip there when he got out of school at age 17.

“I would look up at the hills and say to myself, ‘I wonder what it’s like up there.’ I had no idea you could actually go up on them.”

In Braemar, he met an Australian couple from Melbourne. David was a printer and Caroline was a librarian. He talked with them and they told him they spent the free time and money they had traveling the world, seeing things and going to places they’d never get to unless it was by specific intention.

“I never realized you could live a life like that,” Tim said. “It had never occurred to me it was possible.”

After that, Tim started hillwalking. He corresponded with David and Caroline and they invited him to come to Australia, which he did for one of his holidays in the 1980s. About 10 years later, he took unpaid leave from his job and went again, for a couple of months.

“One of my mates at work said, ‘What are you doing taking unpaid leave.’ I was 33. I told him, ‘I’ll never be this age or this fit again. I’m just going to go’.”

Tim does hillwalking when he can. He belongs to an outdoor club in Nottingham.

He’s 56 and this is fourth Challenge. His aged mother is looking after his dog while he’s on this one.

I asked him if David and Caroline are still alive.

“Yes,” he said. “They changed my life.” His eyes filled with tears. I asked if he still kept in touch with them.

“Yes,” he said. “They’re coming over in June.”

Cape Wrath is good but I think your Polish acquaintance should head for Scrabster. That’s a name to write home about!

Will you be going/Did you go through Pitlochry?

Great fun to follow you. A little envious as my current, temporary leg wound curtails any such adventure. I’ll be reporting on your progress at our 55th on Saturday.