One of the aspirations of this trip is to walk the Moray Coast–roughly 100 miles, from Inverness to Fraserburgh–within view, and if possible within touch, of the water.

The Moray Coast Trail, a recreational path for walkers and bicyclists, runs for only half the distance, and isn’t always on the water. Much of the rest of the shoreline is industrial park, military reservation, nature preserve, and private farms. How much will be accessible, even given Scotland’s remarkable public access law, remains to be seen.

The first test was at the northern end of Inverness.

I walked into town on the end of the Great Glen Way, crossing on pedestrian bridges over the River Ness, which connects the Caledonian Canal and Loch Ness to the Moray Firth. On an island in the river I finally saw the Loch Ness monster, come ashore.

I passed an old block of stone cottages.

I passed a World War I monument under renovation. I always stop for these. This one says it was dedicated in 1922 “By Colonel the Mackintosh of Mackintosh / Lord lieutenant of Inverness-shire.”

It listed an unbelievable number of engagements. About 750 men from Inverness died in the war.

Inverness has several handsome bridges over the river.

The route to the much larger Kessock Bridge, which spans the confluence of fresh and salt water, goes through an industrial area. In this day and age that means more storing and selling than making.

This would be a first-strike site for some of the Challengers I’ve met in past years, who view wind farming in the Highlands as an abomination. These objects, which I first thought were some sort of boat, are turbine blades.

These are pieces of the tower. It’s hard to show scale, but they’re gigantic.

I walked past the home stadium of the Inverness Caledonian Thistle Football Club. Soon after that I got to the entrance of a landfill, which is still active, although the sign out front says it stopped taking general refuse a dozen years ago. The driveway went by a building next to a raised truck-weighing ramp. Parallel to it was the exit lane, at grade level. That’s the route I took. I could see the hair on the top of the head of the man minding the scales. He didn’t turn.

There was a slight smell of garbage, but most in evidence were masses of residential trash bins, recycling boxes, and bulk trash containers full of broken bicycles and other metal goods.

I walked down the road until it stopped. To my surprise, at the end was a small building and a “Highway Maintenance” truck parked next to it. Fifty yards away a man was standing; possibly he was urinating.

I figured that if I got past him, every step would make it harder for him to catch up and confront me. So I kept walking into the field of wet grass and gorse. I didn’t look back.

Soon I was at a rip-rap shore at a cove that was mostly mudflats, as the tide was out.

I was where I wanted to be. I cut across the mudflats where I could, but frequently came to places where a trickling tributary made the water just deep enough to ensure that over five hours my feet became thoroughly wet.

I passed a golf course, which had several holes paralleling the shore. For the next several miles–long past the links–I saw golf balls in the water. At least 50. Some in groups, carried up the coast by tide and wind.

I walked and walked, and eventually got to my destination, Ardesier.

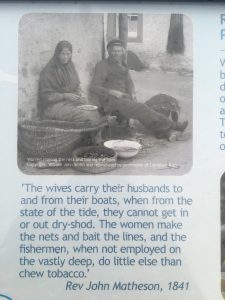

It had once been a fishing village, with 50 boats taking Kessock herring and salmon coming and going from the fresh-water tributaries. I’d heard there was a tradition, here and elsewhere on the coast where the tide exposes huge mudflats, of fishermen’s wives carrying their husbands on their backs across the mudflats to their anchored boats, so the men wouldn’t have wet feet at the start of the day. It seemed hard to believe, but a historical marker I later passed confirmed it.

In any case, it was time for me to slow down.

It had rained on and off all day. I was very happy to make landfall about 8 p.m. at a bed and breakfast run by a man named John Ross. The first day of bushwhacking had worked out.

Golf balls in the water! So much better than plastic bags.