I didn’t bring either sunglasses or sunscreen on this crossing. I wish I’d had both.

The high latitude—Mallaig, where I started, is one degree south of Juneau, Alaska—and long days were perfect for sunburn. After several days I was developing one on my arms. I mentioned this to a woman named Cathy, whom I met taking a break on a gravel track heading toward Mar Lodge.

Cathy, 65, is a former cytotechnologist, seamstress, and inveterate hillwalker from Lanarkshire, south of Glasgow. She had decanted sunscreen from a large bottle into a small tube (“it’s not easy and involves a lot of sucking”), and offered me some. I accepted.

Just then, two younger women, Belgians, appeared. They weren’t on the Challenge, and in fact knew nothing about it.

As I was covering my arms with sunscreen, Cathy pulled the bandana that was around my neck aside to show them my TGOC tee shirt (from 2019). We both explained what the event was about.

As I moved on to my face, Cathy stopped and said: “You have a big smear over here,” pointing to my right cheek. Soon she made a similar gesture to my right ear. I worked on that. The Belgian women leaned in to inspect. “And there’s some right in the middle,” she said, pointing between my eyes.

When I was done, they all straightened up.

“Isn’t it nice to travel with women?” the tall Belgian said.

*************************************************

But no risk of drowning.

But you only need to tap your brakes at rhino crossings.

A slightly indignant appeal to reason.

I wonder who the Supervisors are.

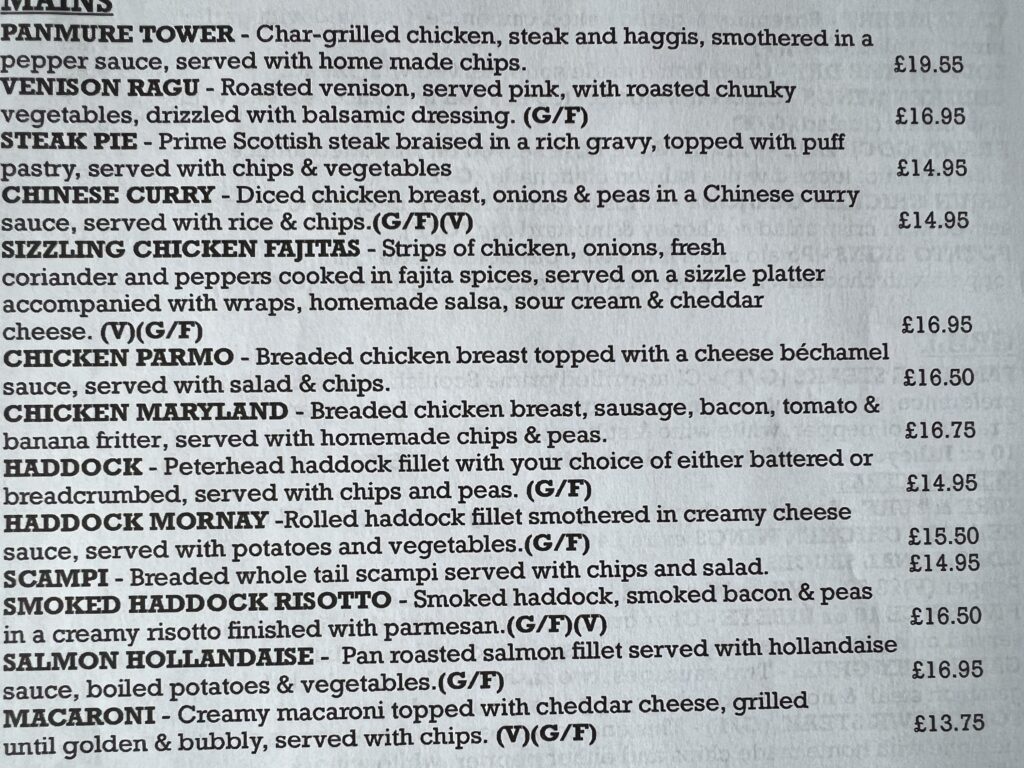

“Chicken Maryland” please don’t come home!

Times change. These are at the end of the same bridge.

All roads lead to lichen.

*********************************************

You sometimes meet interesting people on the farm tracks. Graham, whose farm is along River North Esk, was opening a gate to move his rams—“tops,” he called them—to a field of luxuriant grass. I figured that a trailer full of rams would be an explosive cargo, but he said it wasn’t

“They’ve done it before and kind of have a pecking order now. Of course, it’s different in the fall when the hormones are running.”

The gestation time for lambs is “five months minus five days,” he said. He aims for births about April 15, but higher up the glen where the grass comes in later, the target is April 25.

I met David on the north shore of Loch Lee, tapping the grass and bushes along the dirt road with a long prod. I couldn’t imagine what he was doing. He was looking for the nests of ring ouzels, a species of thrush.

If he flushes one, he notes the spot by GPS coordinates and ties a small ribbon on a nearby bush. Someone will return and count the chicks and band them—a task that requires years of training. The data goes to the British Trust for Ornithology, which has many citizen science projects.

David is a volunteer. He comes up to Scotland twice a hear to do some ornithology project. The ring ouzel population is in steep decline. The last time he found a nest was in 2019.

These are the remains of the Corrour Old Lodge on the 57,000-acres Corrour Estate. The lodge is above Loch Ossian and once had smaller buildings, and possibly large tents, for patients with tuberculosis. Its roof was removed in the early 20th century and it went to ruin. Taxes back then were calculated on the area of roofs and sometimes buildings were unroofed simply to avoid them.

There are places where you can see the remains of more modest dwellings. Sometimes all that’s left is a rough rectangle of stones from the exterior walls, with a line of stones remaining from the wall that divided the building into two parts–one for the people and one for the animals.

Along the way there are bothies—small buildings usually owned by the estate but maintained for use by hikers by the Mountain Bothy Association, a volunteer organization. Some are former crofter houses but most are shielings—residences of shepherds tending sheep in higher parts of glens during the summer.

Bothies differ in repair, cleanliness, and appeal. Many hikers prefer to camp in the grass around them, which is generally flat, and go inside only if it rains. They all have fireplaces, but no peat and rarely any wood to burn in them.

This is the Shielin of Mark bothy.

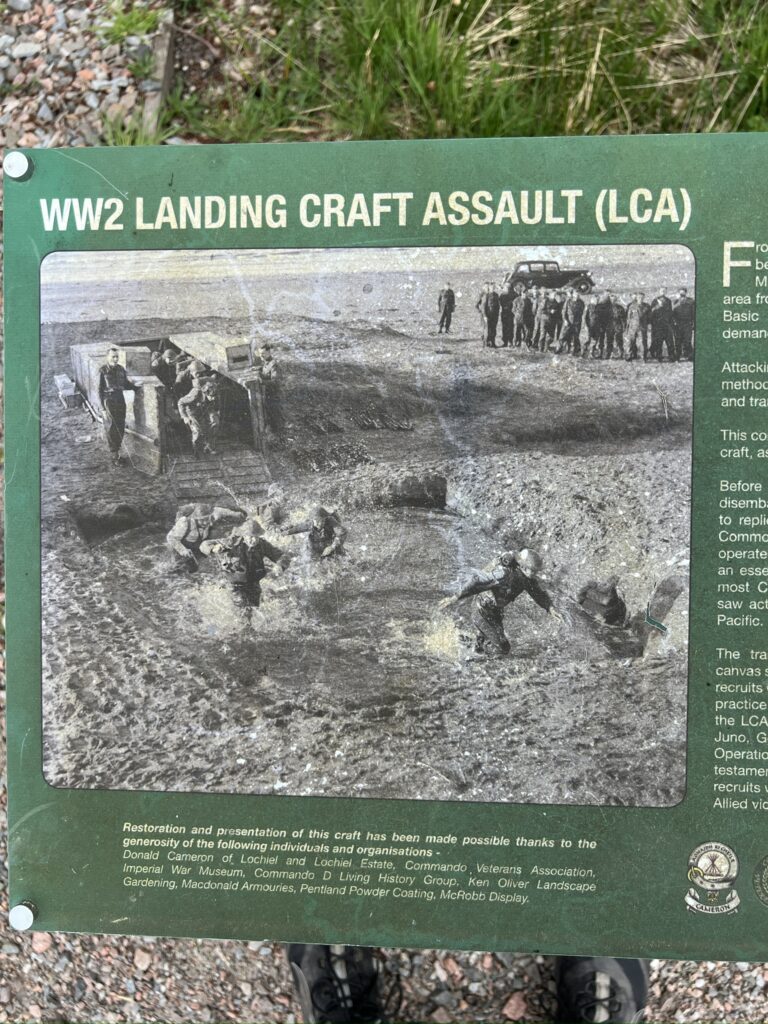

The evidence of Scotland’s warrior history isn’t hard to find. The empty and open Highlands was where tens of thousands of airmen in World War II learned to fly (and hundreds lost their lives in crashes).

In Achnacarry in the Western Highlands commandos from many Allied countries trained in harsh conditions. One of the few outdoor remnants of that activity is the concrete base of a mock landing craft. A photograph from the time shows soldiers emerging from it into water and mud in a simulated amphibious assault.

Every village has a memorial to its dead in the Great War. Most have a plaque for the World War II dead that was added later. This is at Kinloch Rannoch.

I’d seen this one before, in Tarfside, near the end of the walk. It’s hard to know what to make of the description of death in the charnel house of the Western Front as “their bit.” No claim of heroism here, just duty.

Recent Comments