We broke camp after the first night on a grassy verge of a forestry road and stuffed the sopping tents into our packs. Most everything else was wet too, although my sleeping bag was spared. Firing up the stoves didn’t seem like the greatest idea, as it was starting to rain again, so we just headed down the road to Glenfinnan.

The first hotel we got to in the village said it was no longer serving breakfast even though we could see people inside eating. Of course, we didn’t look like the most desirable guests.

A little farther on was an old railroad dining car that had been turned into a cafe, near the train station. We settled in. I had a venison sausage sandwich and series of cups of coffee. Soon, we saw a large number of people outside, a few of whom came into the dining car. They were passengers on a Harry Potter-themed, steam-powered train. (Mark had noticed something I hadn’t—a gift shop next to the dining car selling wands.) The high point of the trip is going over the Glenfinnan Viaduct, the high, beautifully curved bridge featured in the movies. Pretty much everyone but the locals now call it the Harry Potter Bridge.

For the next day we intermittently heard the rhythmic chugging of the engine, and we saw steam rising above the treeline once, but never got a closeup view of the train itself.

At the far end of the village we headed into the hills again, following a stream. We passed a forestry project with stack of cut pine logs.

We stopped for a rest and experienced something frequent in Scotland—rain when the sun is out.

There was a path along the stream for a while, but it eventually petered out. That didn’t matter because we were planning on leaving it anyway, to head up one of the sides of the valley it formed.

The sun stayed out for several hours. It was a beautiful afternoon, with views that you come to Scotland for. The land is brown from last season’s grass and heather not yet in bloom, but patches of bright yellow gorse illuminate the landscape, and flowering bluebells decorate it at one’s feet.

We crossed numerous small streams that flowed down the hill to the larger one we’d left behind. Along one was a gnarled grove of trees newly in leaf.

The walking was steep and difficult. The ground is soft and in places saturated with water that was kept from flowing by grass and moss.

We’d come from the stream far below.

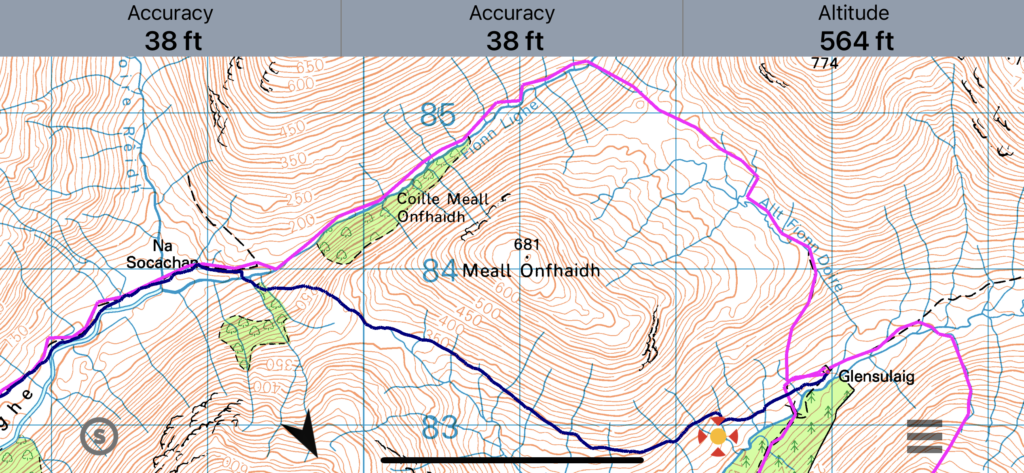

The plan was to go around the north side of the hill we were climbing, but we realized we could cut some distance if we went around the south side. The original route is in magenta, the one we took in blue. Our destination was Glensulaig, on the right end of the map.

We climbed to the elevation of our destination and then walked along that contour line (the 350 meter one) as best we could. We eventually saw in the distance a dark, vaguely conical structure—the ”bothy” where we hoped to spend the night.

Bothies are former dwellings or barns that are maintained for hikers, although they offer little more than shelter. There are usually no bunks. There’s often a tiny fireplace built to burn peat, but as nobody cuts peat for them and there isn’t wood around, the fireplaces are unusable.

We saw a bunch of tents outside this one, which made me think it was already full, probably with Challengers. But it turned out to be a group of 11 teenagers (mostly age 15) on an Outward Bound trip. They were all sleeping in tents, as were the leaders, so Mark and I had a room out of the weather for the night, which had turned quite cold.

We spent an uneventful night and then headed downhill toward Loch Eil. The route took us through another pine plantation.

To shave off some distance we went diagonally through the forest on a track, looking out for a cairn marking a path down to the lakeside Outward Bound Center that one of the leaders, Craig, had recommended. But we didn’t see the cairn or a path.

The track we were on eventually came out onto a cleared area that we were able to go down, although the ground was another version of sloped land holding water. We had to step from hummock to hummock, trying to avoid water-filled holes. It was hard going. Of course, our feet had now been wet for two days.

We eventually got to the bottom, had lunch in a restaurant, and then headed up the Caledonian Canal, an ancient feat of engineering that, with the assist of long lochs reaching deep into the country, created a water route from the west coast to the east coast through the middle of the country.

There were a few people crazier than us.

We eventually got to Spean Bridge, a village where my father and his friend had spent a night on their bicycle trip in July 1936. We were glad to have a room in a guest house, a shower, and dinner in a sports bar.

It had rained every step of the 19 miles we walked that day.

Recent Comments