I spent the night on a small, barely acceptable piece of ground along a stream just below Birse Castle. The Castle (which looks too modern to be a castle) was half-hidden in the trees in the distance. (Here I’ve set up a washstand on the screw of an disused device for blocking water in a channel).

The day involved my last piece of compass navigation. I was in an area where there were two hills named Cock Hill. Each had an ATV track to the summit but not one connecting them. I took a bearing on the map and navigated by it, but it wasn’t necessary. The day was It was sunny day and everything was possible by line-of-sight.

Climbing the heather and sphagnum moss was hard. I hadn’t done it for a long stretch since the first few days of the walk, which seem long ago.

The track took me along a ridgeline, past two buildings and numerous wooden blinds behind which one shoots grouse flushed from the heather by beaters. Here is one of the labels on a blind.

The road eventually headed downhill toward what I really wanted to see: the remains of an airplane that crashed on May 5, 1939–76 years ago this month.

When I submitted this year’s route, my “vetter,” a man named Colin Tock, noted in his comments that I would go by two crash sites of World War II-era trainer aircraft. One was far off the path, but this one was in view of it.

“About 5,000 aircraft crashed in the Scottish hills and mountains during WWII, but it would be impossible to include them all on the website,” a man named Gordon Lyons wrote me several months ago. He maintains a website called Air Crash Sites–Scotland.

http://www.aircrashsites-scotland.co.uk/index.htm

The website records the location of about 300 crash sites from World War II, “the majority of which still contain some wreckage,” he wrote.

This site is one of the earlier ones of that era. The flight originated in Montrose, a town on the coast where there was a military air base. (It’s also where Challengers officially sign out after finishing their walks, and where celebratory dinners are held on two successive nights.

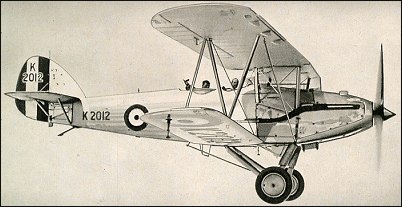

The airplane was an Audax Harrier, a two-seat craft that was a common training plane. It had a Rolls-Royce engine, “and had a maximum speed of 170mph,” according to one description I found on the web. “For armaments, it was equipped with two .303 machine guns–one forward and one aft. I could also carry four 20lb bombs.”

Here is what it looked like:

aviator.org

And here is what its remains look like from the trail.

The most visible remnants today are parts of the airframe of the fusilage. There is a faint trail to it; it’s impossible to tell if it was made by human beings or animals.

Most prominent is a frame of rusted steel and corroded aluminum tubes and joints that together make a slighly humped elongated rectangle. There is a sheet of aluminum bulkheading what I took to be the aft (and downhill) end of the airplane.

It appears to have crashed pointed uphill about 45 degrees to the fall line. The fact that much of the frame of the fusilage exists intact suggests to me it was a relatively soft landing for an unplanned one. Both people on board survived.

Scattered around it are pieces of metal tubing in various states of disintegration. Tubular struts about the size seen in bicycles appear to have been the chief engineering strategy of the design. A round piece of aluminum (one-third missing) was on the ground in the middle of the fusilage, covered with rabbit droppings. A square metal box with a round port, which appears to be a fuel tank, was nearby.

The front of the frame had two upturned pieces of tube, which gave it a praying mantis look.

There was a light breeze and the sun was out.

To the left was the top of Clachnaben, one of the few hills I’ve seen with a rocky summit. At one edge of its top was a rock formation that looked like a head of spiky hair blown straight up by the wind, and to the south, a pink stone road I would soon be walking down.

You could sight the landscape through the wreckage.

To the east were perhaps 30 wind turbines, their three-armed blades moving as if there was barely enough wind to turn them.

I heard an occasional bird call, but other than that it was silent except for the wind. It made a mournful whistling sound as it blew over two pieces of rusted tubing at the top of the frame.

I’d brought my little plastic bottle of whiskey and the metal cup from my thermos. I took a wee dram and poured it over the highest and most complex joint of the frame–five tubes coming together. It darkened the rust of one of the tubes before evaporating. I took a wee dram myself and drank to the memory of Pilot Officer J. D. Lenahan and Flight Officer Rolf E. Atkinson.

They were lucky when their plane came down here. But their luck did not last.

P/O Lenahan died on September 9, 1940, near Coventry, England, when his plane was shot down in the Battle of Britain. He was 20. F/O Atkinson died on September 27, 1942, when his bomber with a crew of seven disappeared on a night raid on Flensburg, in northern Germany. No trace of the plane has ever been found. He is listed on the Runnymede Memorial, which holds the names of 20,000 Commonwealth airmen lost and without graves.

I hope the bones of the aircraft they learned to fly in sits on this hillside a long time, in honor of them and their brothers.

Recent Comments