The west coast and western islands of Scotland are pocked with the remains of churches, monasteries, forts and settlements of uncertain purpose. Many are on the absolute edge of the land. It’s hard to know whether the people who used to live in them had barely managed to crawl ashore from someplace else or had barely managed to hold on as someone tried to drive them into the sea.

Actually, both happened.

Some of the oldest settlements with a historical (as opposed to purely archaeological) record were of people who sailed to the western islands from Ireland and Scandinavia. At the same time, this is the place where the written word (and some argue, the core of western civilization) retreated to as the “Dark Ages” descended over Europe.

My host, Paul Richard, and I visited a place where this history resides–the remains of St. Blane’s monastery on the island of Bute.

Paul is the former art critic of The Washington Post (46 years) who left five years ago. He has been coming to Scotland since the 1960s. He and his wife bought seven acres and a stone house between the road and the sea in 1994. They live there six months a year.

Paul is a born teacher, lecturer and guide. In addition to immense knowledge of art and literature, he reads widely in science and history. He’s the kind of person who can recite the first 20 lines of a poem from T. S. Eliot or excerpts from an interview with Marcel Duchamps as a way of illustrating a point, not showing off. Rick Weiss, a former member of the Post science pod, and I used to joke that we got course credit for eating lunch with Paul, working toward a Master’s in General Erudition.

Paul and I drove over to Bute, which runs northwest to southeast across from Paul and Deborah’s house across a body of water called the Kyles of Bute. (There are actually two kyles, one on each side of the island’s northern end). Getting there requires a 12 minute ferry ride.

The northern end of Bute is virtually uninhabited. We headed for the south. It faces the Irish Sea, and is where people have been arriving and departing for six thousand years.

We stopped for lunch at a tea room in a concrete box on the beach in Ettrick Bay. It apparently has a good reputation, as all of Paul and Deborah’s friends know it. We had soup, salad and dessert.

Our waitress was a handsome woman, very little over 20. She had striking blue eyes. Paul, who is good at meeting strangers and likes the occasional rakish aside, asked her at one point: “Are you a Butean?”

“No, I’m, a Brandane,” she said.

I don’t think she got the play on words. But she did demonstrate the use of this unusual designation. People who are native to Bute are Brandanes, a reference to St. Brendan, who is supposed to have come to the island more than 500 years ago. The origin of this word is even harder to infer than is Glaswegian for people who come from Glasgow.

On the edge of the beach outside the restaurant was a plaque honoring a blacksmith from Bute, Andrew Blain Baird, who flew the first all-Scottish airplane there in 1910. The Scots like historical markers (and that is just one of the reasons I like the Scots).

We continued south and came to a sign that seemed to announce we were entering a zone of unusual continuity, a geohistorical Möbius strip. (Of course, the sign makes sense for a road that’s a loop).

The remains of St. Blane’s monastery was down a long country road, which continued on. A couple of cars were parked on the shoulder. The sky was gray and the land was green, Scotland’s unofficial national colors.

We walked up a slope along a “drystane dyke,” an unmortared stone wall. It was about four feet high, wide at the bottom and with a single course of large stones on the top. The two sides lean against each other and hold each other up. Between them is a core of rubble–stones too small to do anything but fill space. Every 10 feet or so a flat stone protrudes, a step for someone wanting to climb over.

A section of the wall was down, giving a glimpse of how it was built.

Going up the slope we passed a boy of about 12.

“Do you know you’re about to enter a monastery?” Paul asked.

“Yes,” the boy said.

“Would you like to be a monk?”

“No thank you, sir.”

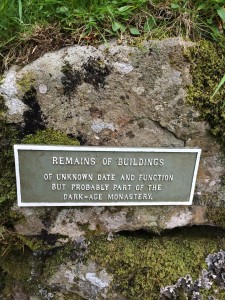

At the top, the ground formed several rough terraces. Along the highest one was a wall of cliffs, which were mostly hidden by trees and vegetation growing from cracks. At the base of the cliffs were jumbles of rock and a few fragments of wall–all that remained of the monks’ cells. Overhead, ravens raucously came and went from the trees. I took them to be the spirits of the monks, still defending their privacy.

The place was full of mystery, and mysteries.

The monastery was on the edge of sea. But the sea could only be seen with difficulty by its inhabitants. Was this a strategy against homesickness and distraction? Nobody who sailed by could imagine there was a monastery behind the cliffs. Was this what allowed it to survive for so long?

Where did the monks sleep as they moved these huge rocks to build their cells? What did they eat and how did they cook? How did they put up with the cold in winter, the midges in summer, and the rain year round? And what makes such walls eventually fall down?

What was the purpose of a large ringed enclosure, which a sign called “the cauldron”?

When was the vallum–a wall separating the monastery from the secular world–built? And was it necessary even before there were people outside who might have wandered in?

And all this to let the long-gone inhabitants spend lives in silence and self-denial, praying and copying texts to keep and spread the Word.

Paul did point out that while it seems like a primitive life, these people were among the few who could use the most powerful information technology of the day–reading and writing. This was the Silicon Valley of Europe!

Exactly who St. Blane was and how he got there is a little unclear.

The version told on a panel at the site says that a man named Catan founded the monastery in the late 6th Century and became enraged when his sister, Ertha, became pregnant out of wedlock. He put her and her newborn son to sea in an oarless boat. It drifted to Ulster in the north of Ireland. There, the boy–Blane–stayed for seven years before returning to Bute, where he eventually succeeded his uncle as abbot.

The version in a witty travel book about the island by a writer named David McDowell is slightly different. In it, Catan sent his nephew, Blane, to Ireland to be trained in the faith at Bangor Abbey.

“Seven years later, in about AD 600, he returned allegedly in a boat without oars, a fact which smacks of either the miraculous or the improvident,” McDowell writes.

The monastery was burned by Viking raiders in 790, and rebuilt by their converted descendants about 930. The walls of the church that still stand, however, are from about 1135.

Two families–Scottish–were inspecting the ruin. Paul engaged them in conversation. One included this girl in an American flag sweater.

Inside the church on the grass floor were several flat gravestones, rubbed smooth. Outside the walls was a graveyard on two levels, the higher for men and the lower for women.

The place was quiet and devoid of trash and graffiti, but full of presence. It was a place where objects become symbols or remind you of other things.

The empty window of the church was an eye through which the people of the present could see what the people of the past saw.

A gravestone brought to mind some lines from Emily Dickinson.

And so, as kinsmen met a night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

Between the upper and lower graveyards was a sunken path walled in stone.

On one of the facing stones the lichens had made a map of the clans of Scotland.

Dangling down was an inspiration for a drawing a monk might have made in the margin of an illuminated manuscript.

And on the top, a miniature Zen garden.

We stayed about an hour and then walked back down the hill into the world as we knew it, and to the present day.

Still listening. Having dinner with Ellen tomorrow night, your ears will burn.