The 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I is six months passed. The centennial observations are over and the museum shows and dramatic performances marking the end are in their last days.

The Great War is receding into deep history, soon to be beyond the recollection of a single person on earth. Already the millions of dead are names and stories only, no longer brothers, fathers, husbands, or sisters.

The acknowledgment of this catastrophe, however, will continue for a very, very long time, as it should.

Every city, town, and village in Scotland (and in France and lots of other places, I assume) has a memorial to the dead.

I’ve seen them on each of my crossings in The Great Outdoors Challenge and find them moving, although it’s hard to say why. The one reason I can articulate is that they represent the enormous number of people willing to give their lives for a public purpose with little debate or hesitation—something that doesn’t exist in the Western world any more.

For which I think we can say: Thank God.

Of course, there were reasons other than patriotism and altruism for which people went to war in what became known as the Great War. An escape from cruelty and deprivation was the most obvious alternative one.

Readers of the first chapter of “Akenfield: Portrait of an English Village,” (1969), an oral history of a village in Suffolk, England, by Ronald Blythe, will learn that serfdom existed in Britain until well into the 20th Century. The Great War gave young men an opportunity to escape it (at a risk they didn’t comprehend, of course). It gave them enough to eat until they were killed.

I’m in Dundee as I write this, and just learned at a museum at a restored jute mill (Verdant Works) that this city supplied an unusually large number of volunteers at the start of the war. The reason was that so many men were unemployed. They were unemployed not because of economic downturn, but because of rationalized exclusion from the labor force.

Dundee’s dozens of jute mills preferentially employed women and children in their factory force because they could be paid less. When boys reached adult age, they were terminated. Even in intact families, often it was the women who earned the paychecks and the men who tended the babies.

This is what the men of Dundee got for work once the war started–slaughter at Neuve Chappelle. That battle, in March 1915, was full of Dundonians, in the 2nd, 4th, and 5th battalions of the Royal Highlanders.

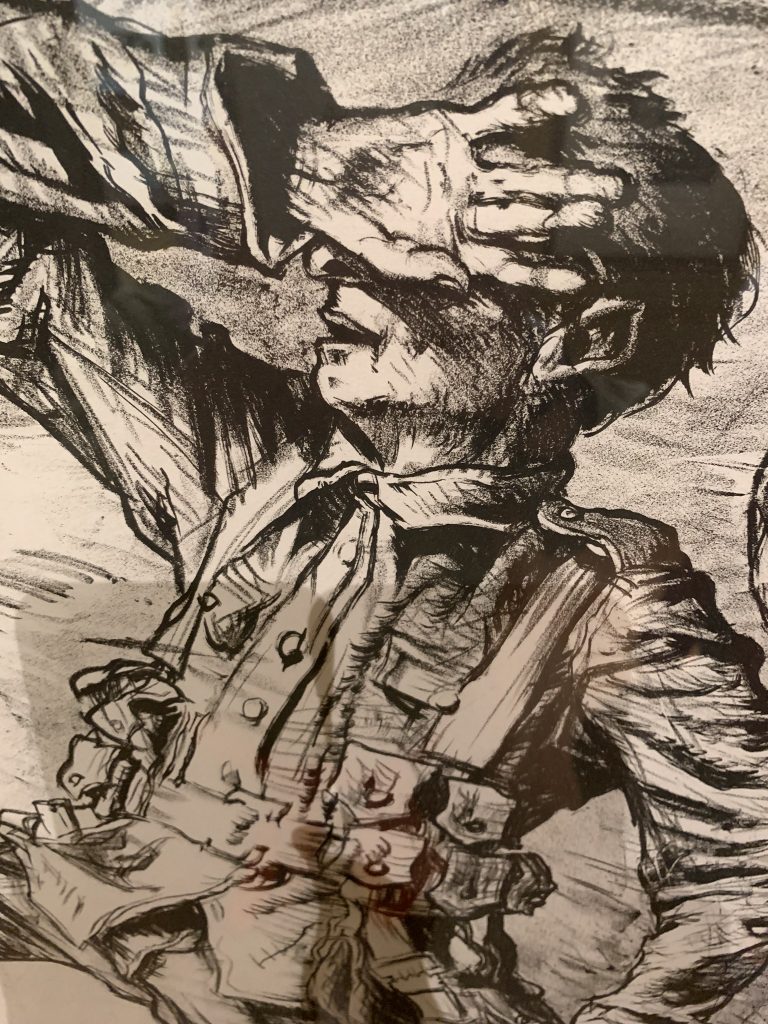

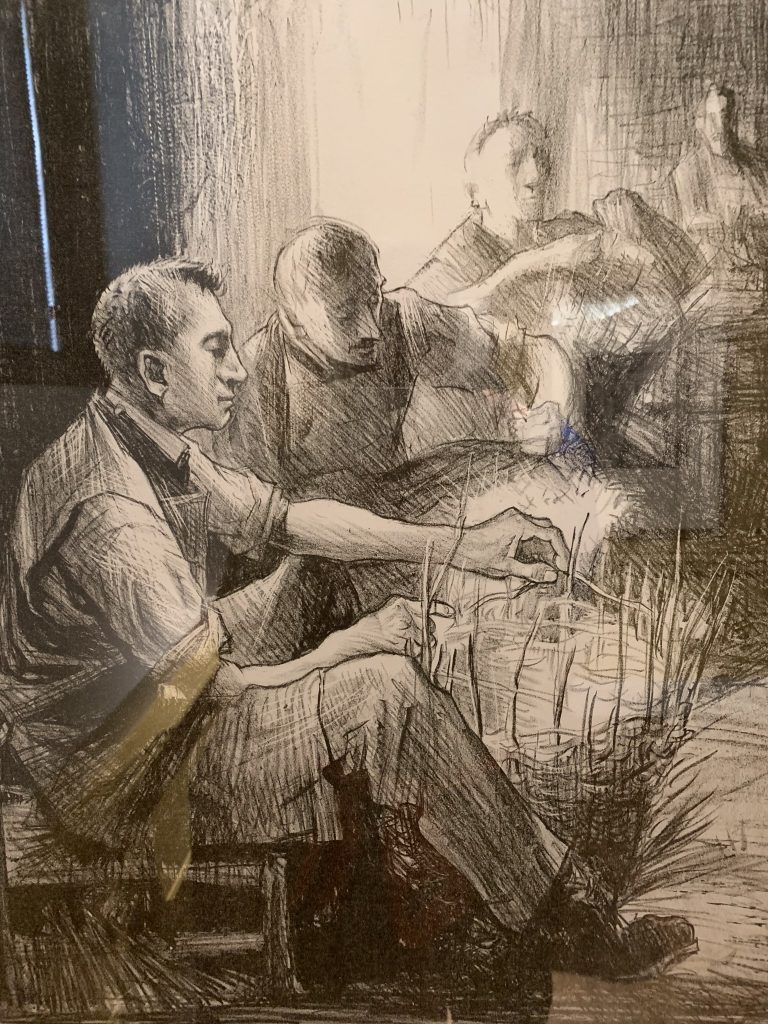

At the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow, before the Challenge, I saw a show of prints that Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956) made in 1915 to raise money for St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blind Soldiers and Sailors.

The monument in Glasgow gave the numbers: 200,000 people from the city serving in the Great War, a number that’s hard to comprehend.

Here are a few of the monuments I passed on my crossing of Scotland.

I saw only one monument that was damaged and not well kept, in the hamlet of Kinnell, next to a church that was going to ruin too. But even it had a few artificial poppies left at its base.

We do not know these people, and many of us—certainly including me—don’t believe they died for a good cause. But we should never forget them.

My last post will be about how the Great War touched my family.

Recent Comments