Some people approach the Challenge with an excess of planning and conversation. (That, I suppose, would be me.) There are many, however, who do it without brouhaha, and with a certain amount of spontaneity. At the extreme, there are people like Stevie O’Hara, who do it silently, like a hard piece of manual labor.

Stevie–“Scottish, from Irish stock”–is 56 years old and making his fourth crossing. I met him briefly the third day when I stopped at a hostel for tea and lunch with a couple other people. He was wearing a wool hat and dirty gaiters and carrying a tiny pack. He had a big jaw and wide-set eyes and looked like a mountain man. He didn’t say much. He’s on the left.

I ran into him a couple of days later when I was preparing to leave my camping spot beside the River Findhorn at a place called Easter Strathnoon. We were both going up and over the watershed and down into the valley of the River Dulnain on the other side. This is the view up from the river.

I met him at the gate blocking the track up the hill. (All the gates are unlocked; you just open them and relatch them after you go through). He was taking off his long underwear and generally getting ready for a strenuous climb. I considered waiting for him. However, I intuited he was a fast walker, and that waiting would either obligate him to walk with me, or would be pointless because he would outpace me in a few minutes. So I just said I’d see him on the trail.

I walked a while and looked back. He was a black spot at the bottom of the hill. You can’t see him, but this is the view.

Very soon, of course, he caught me. We talked for a while then, and later on. What follows is from those conversations.

Normally, Stevie walked alone. On the Challenge last year, however, he’d walked for a while with a woman named Heather, a nurse, and found it pleasant. Just yesterday he’d walked with the two Germans who left after me from Strathcarron (and whom I still haven’t met).

“I’m learning new habits I never had before,” he said.

Stevie lives in a place called Wishaw, in the Clyde valley, 15 miles southeast of Glasgow. He said he runs “a wee small ground-works company” that builds foundations and driveways. It’s basically him and a few young men he hires when things get busy. The business allows him to take off when he wants. (“That’s why I started it.”) Nevertheless, he admitted this is a busy season. “There won’t be any more holidays this summer.”

Stevie’s father was a bus driver, and his father’s father, too. He learned to love the outdoors when the family would rent a cottage in the mountains for two weeks and he would run around with his shoes off. From an aunt, he said, “I learned to love wild birds.” He described some he’d seen in the last few days, including a once-endangered red kite.

When he was young he walked with his brother and a cousin. Often, “it was a rush to get to the next town and the next bar.” As he got older and they got busy, he walked alone. He was married once; “It wasn’t for me.” He has no children; “That’s my one slight regret.”

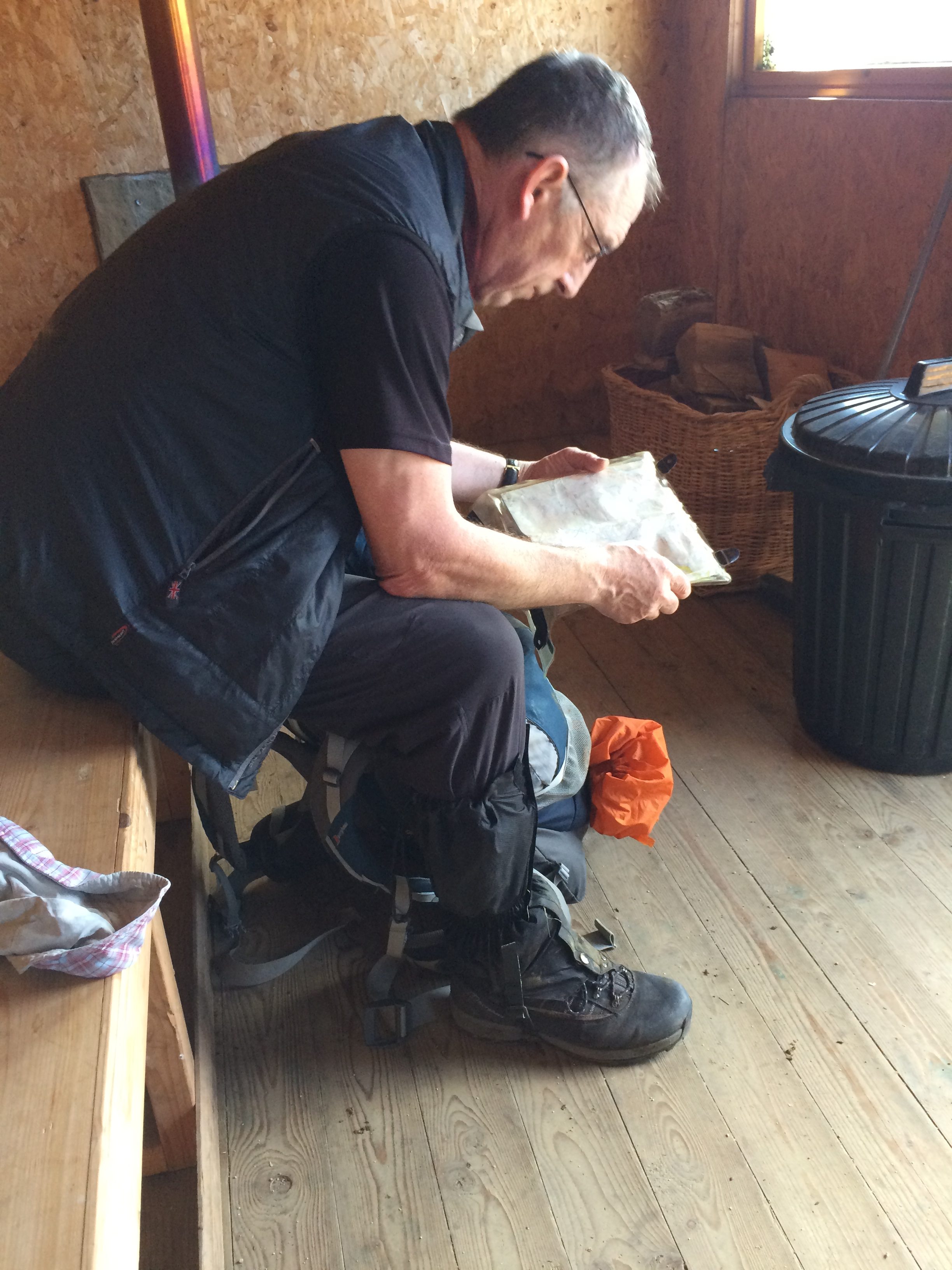

Stevie caught up to me at a new, green bothy. We sat inside looking at maps. Mine was newer than his, and it showed that the track went the summit of a nearby hill, but not over. Stevie was disappointed it went that far. “I was hoping for a bit more navigating.”

He was working on climbing all the Munros, which are the 284 hills in Scotland that are over 3,000 feet. Early in the Challenge he’d climbed four in one day. He’d started walking at 8.30 in the morning and finished at 10.20 at night. He climbed into the tent, made a cup of tea and fell asleep.

He looked at my backpack. “You’re not going over many Munros with that rucksack, mate.” I explained I was carrying seven pounds of electronics. It’s my standard excuse for this unusual form of American obesity.

Stevie may have become more sociable, but he nevertheless took off alone toward the summit of Carn Dubh ‘Ic an Deoir. I followed a while later.

There were great views from the 750-meter top. There was a pyramidal cairn of rocks in the lee of which I had a lie-down in the sun. When my eyes were open, this is what I saw.

There was also a cement piling with a triangulation point put by the Ordnance Survey, which is the British mapping agency. It is used to take cartographic measurements. I put my Ordnance Survey map on it and took a bearing for the road down the other side, where I was heading. It probably wasn’t necessary, as the road would likely be in view the whole way down. But if fog rolled in, I would know what direction to go. (And I hit it exactly, following the compass.)

I turned east and walked up the glen until I reached a building called the Red Bothy. I’d had lunch and didn’t have to stop. But I have a “leave-no-bothy-unexplored” rule, so I walked around it. There, in the lee, in the sun, was Stevie.

He’d taken off his boots, fired up his cooker, and had had some noodles and sausage (and a lie-down).

I sat down in the sun and we talked briefly. But I didn’t want to get too comfortable, so in a few minutes I got up. It was my turn to head off alone.

“I have to get more of this track behind me,” I said.

He nodded understandingly: “You go’ qui’e a big ki’.”

Quite a big kit–that would describe it.

I left at 2.25 in the afternoon. I crossed the River Dulnain and started another long walk up a hill on a gravel road. The top of that watershed was the border of the Cairngorms National Park, and in the distance, the Cairngorm Mountains, Scotland’s biggest range.

Stevie passed me at 3.33 p.m. He had taken off his shirt and was carrying his pack bare-chested. “Cracking on,” as they say. And then, on the final pitch right before the turn down the other side, I found him sitting on a rock pylon beside the road. There was another a reasonable distance away and he gestured to it. I sat down.

We looked back at the summit of Carn Dubh ‘Ic an Deoir. If you enlarge the picture you can see the faintest hint of a nipple on top, which is the cairn. That wasn’t where we’d started from that morning, and we still had quite a ways to go. We agreed the Challenge was challenging.

After a few minutes, Stevie said: “I like being in the moment, but it’s on reflection that it’s fucking brilliant. Maybe in the pub tonight, or in a few weeks, you forget the pain and remember only the beautiful days. And this might be one of them.”

We stayed together going downhill. A mountain biker on his third outing on a bike just arrived from Colorado passed us on the way up an ascent it was painful to contemplate. He was making a loop; we saw him again a couple of hours later at the bottom.

Stevie and I walked into Aviemore, where I had a B&B room booked and he had no plans other than to meet his friend Heather, a Challenger arriving by another route. Stevie doesn’t plan ahead much. He buys his food along the way, often walks farther than his announced itinerary, hopes there are rooms available if he wants one.

We stopped at the Cairngorm Hotel, a stone building that looks like a small castle. He bought the beer and I bought the potato chips, and we sat outside at a table and toasted the long day behind us. He decided he might fancy a bed that night, and went inside and booked a room. He convinced the desk clerk to give him a discount because the room was over the bar and likely to be noisy.

He came back outside to await making contact with Heather. He offered to buy another beer, but I said I needed to be off to find my B&B.

I saw Stevie three days later in Ballater, my next in-town port of call. He and Heather were in the pub at the Alexandra Hotel. It was just after last call.

Recent Comments