So I got off a little before 11 o’clock in the morning, the last of five people to sign out from this particular starting point of The Great Outdoors Challenge.

Here I am. I promise there won’t be many of these.

As you can see, it was a beautiful day. There’s supposed to be more of them ahead.

I got up onto the towpath of the Crinan Canal as soon as I could. It gave a great view of low tide in Loch Fyne.

There were a few walkers, but I was pretty much to myself. It wasn’t a bad way to start, although I do hope I run into some other Challengers. But I may not. I’m near the border of the event territory and the distribution of walkers pretty much follows a bell curve, with the majority in the middle of the territory, north of where I am.

The Crinan Canal opened in 1801, a time of great canal building in Britain. It’s only nine miles long but it served a useful purpose. It allowed vessels to avoid going around the Mull of Kintyre, which is the southwestern tip of the Kintyre Peninsula, which hangs down like a flaccid penis over Northern Ireland. Something to avoid! (And the seas can be rough there, too).

Steam-powered vessels—“puffers”—carried coal and other goods inland along it for a long time. Now, its water is navigated by pleasure craft. I watched several sailboats go through the openings of swinging bridges, and into locks, which are still opened by human muscle power.

There are 15 locks and seven bridges. It seemed that all the lock-keepers houses were still standing. In places the canal widened into large ponds the color of over-steeped tea. It was an area somewhat out of time.

I talked with a canal worker named Russell Livingston, and threw a well-chewed chunk of wood into the canal for a retriever named Rufus.

The antique feel of things was aided by some of the berthed boats I passed, which could have been left over from “The African Queen.”

My original route did not have me going to Crinan, the terminus of the canal. But Mr. Livingston convinced me it was worth it, and the detour was only three miles round trip. Plus, I was getting hungry and he said there was a coffee shop there.

I hid my pack in what appeared to be a closed car-repair business—lots of cars, no people—and walked up to Crinan. I encountered Rufus and his master again (they’d driven there) and one of the sailboats I’d watched go through a lock earlier in the day. I had lunch and two cups of coffee—good, put perhaps not worth three miles.

Finally I headed away from the canal, crossing a large marsh on a straight, hard road. I passed a tree plantation where a clawed crane was loading logs on a truck. I walked down a farm road and passed the first sheep and lambs of this crossing. I eventually saw the ruins of a manor house, and closer to the dirt road I was on, a church with a sign that said “Dangerous Building.”

Feeling courageous and sore of foot, I took the road into the church. A red car was parked in front of it. In the churchyard was a woman named Christine Young, who was tidying up the plantings in front of the gravestone of her husband, who died four years ago.

She told me the church, St. Columba’s, was Episcopal and the home church of the Malcolm family, which had been lairds of the Poltalloch Estate for fourteen generations. The estate house hadn’t been occupied since 1954–the family couldn’t afford the roof tax—but the church still had a service one Sunday a month.

Christine, who was about my age, lived in an estate cottage near the church. She’d moved up from southern Scotland in her thirties to do her internship for nursing school, which she’d gone to after an earlier marriage had ended. Her late husband was a psychiatric nurse. She’s a general medical nurse at a hospital about 10 miles away, a year and a half from retirement.

She let me into the church, which she said is always open. It was dusty and suspended in time.

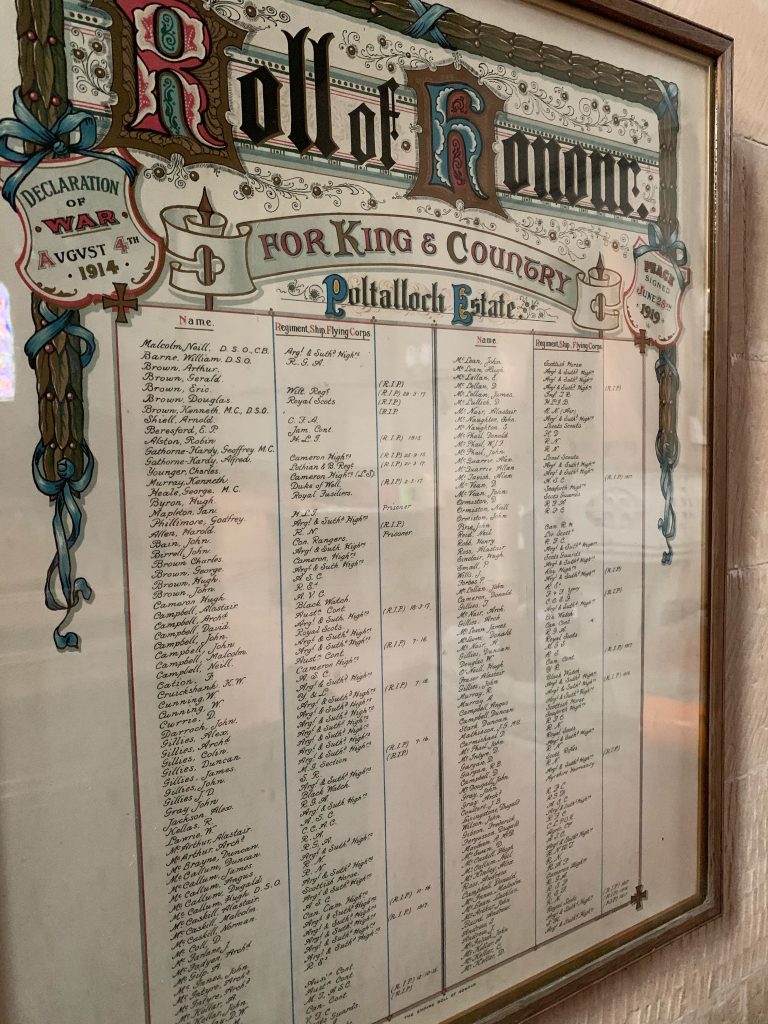

On the back wall were two framed “rolls of honor,” one from each world war. They listed members of the Malcolm family and workers on the estate that had served overseas or in the home services. I didn’t count, but there were probably a hundred from World War I, and half that many from World War II.

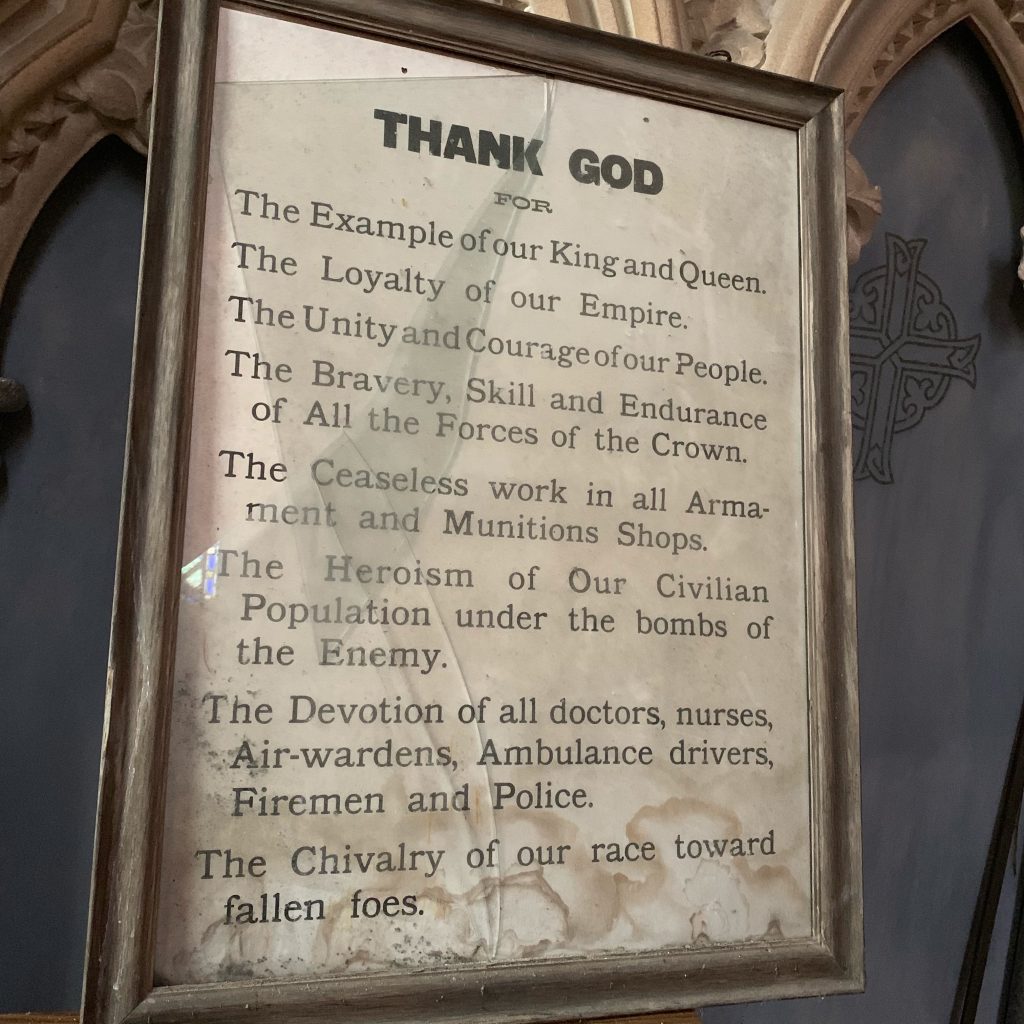

In the sacristy was a framed broadside under broken glass thanking the king, workers in munitions factories, and “the heroism of our civilian population under the bombs of the enemy.” It was obviously from World War II.

After a while I headed up the dirt road toward Kilmartin, my destination for the day. It has a museum devoted to Neolithic, Bronze Age, and medieval Scotland, and a hotel where one can buy dinner, and a sports field where walkers are allowed to camp.

Along the way I passsed a stone circle, of which there are many in Scotland. Their function isn’t fully understood, but appears to involve astronomical or seasonal observations.

And several cairn-covered graves, called “cists.”

At last I got to Kilmartin. I set up the tent and went inside the hotel for dinner, and to write this.

I’d walked 14.1 miles, according to the walking app on my phone. My feet are not quite up to this yet. Tomorrow I’m heading into the hills—it’ll be a while before the next post—and the distance will be greater.

Nice photos! I especially like the one of you. And how auspicious to set off on a lovely day.

Not the least impressive deed, by my measure, was your choosing the Kilmartin field rather than the hotel as your shelter for the night.

A bonnie song for your travels:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hKvB3g3HEPQ