You know you’ve arrived, for good or ill, when your last name is turned into a noun (quisling) or modified to create one (spoonerism). Something like that happened to two Scots brothers, William and John Hunter.

William (1718-1783) and John (1728-1793) were both physicians and anatomists. William was London’s leading obstetrician at a time when few babies were delivered by men. He also wrote a famous treatise on diseases of cartilage. John collaborated with Edward Jenner, the inventor of the smallpox vaccine, and advocated the conservative treatment of gunshot wounds. Each had anatomical collections with thousands of human and animal specimens. John once bribed the member of a funeral party to give him the skeleton of a 7-foot, 7-inch “giant,” and fill the coffin with rocks.

There is a Hunterian Museum in London and a Hunterian Laboratory in Baltimore (at Johns Hopkins) named after John, and a Hunterian Museum and Gallery in Glasgow named after William. I took the bus out to the University of Glasgow to visit the latter.

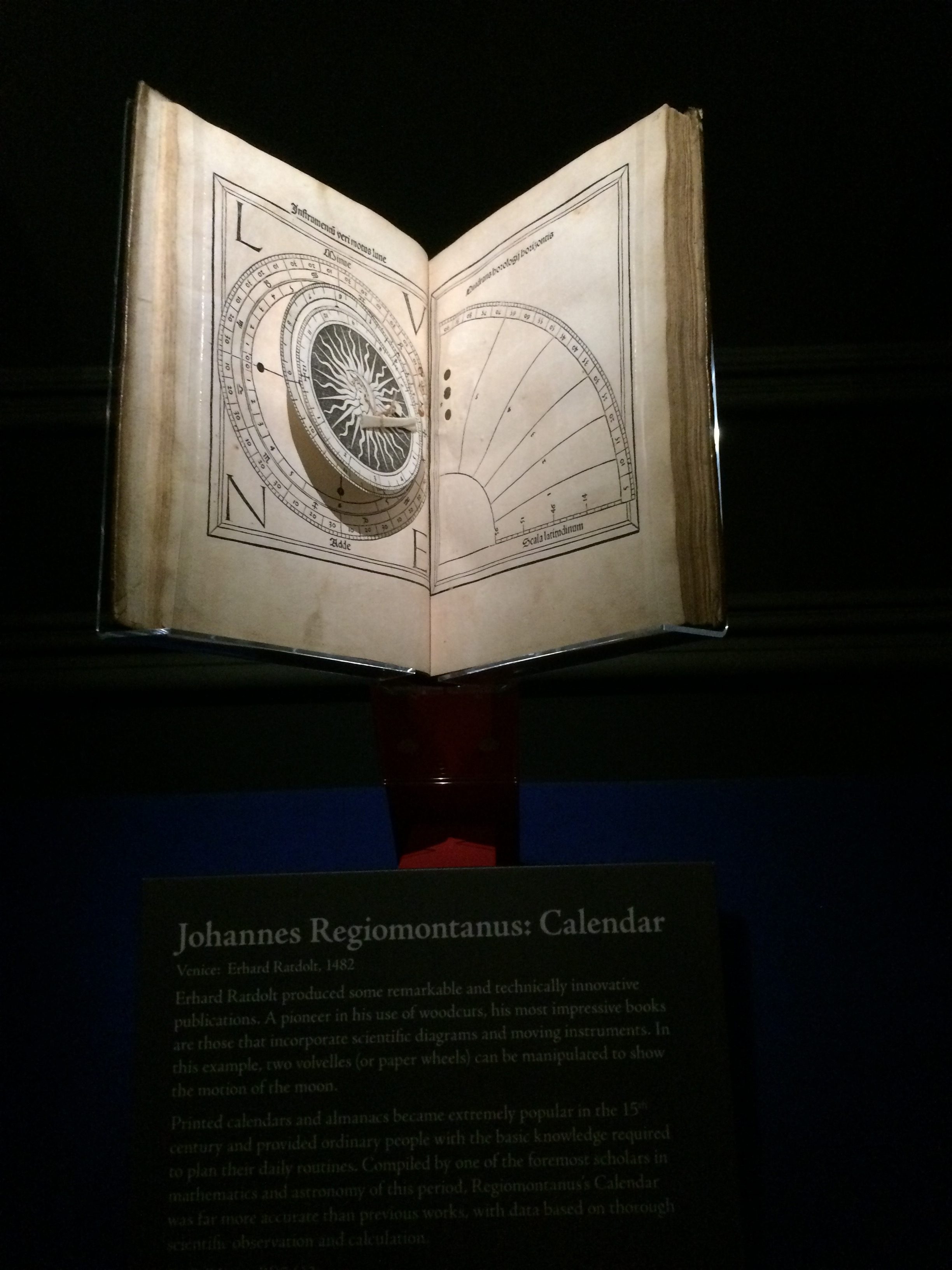

William was a bibliophile, too. The gallery had a show of books printed before 1501 (known collectively as “incunabula”) built around several dozen he acquired. The university owns a number of volumes in which only a single copy is known to exist. On display was a book that had revolving paper disks (“volvelles”) illustrating astronomical phenomena.

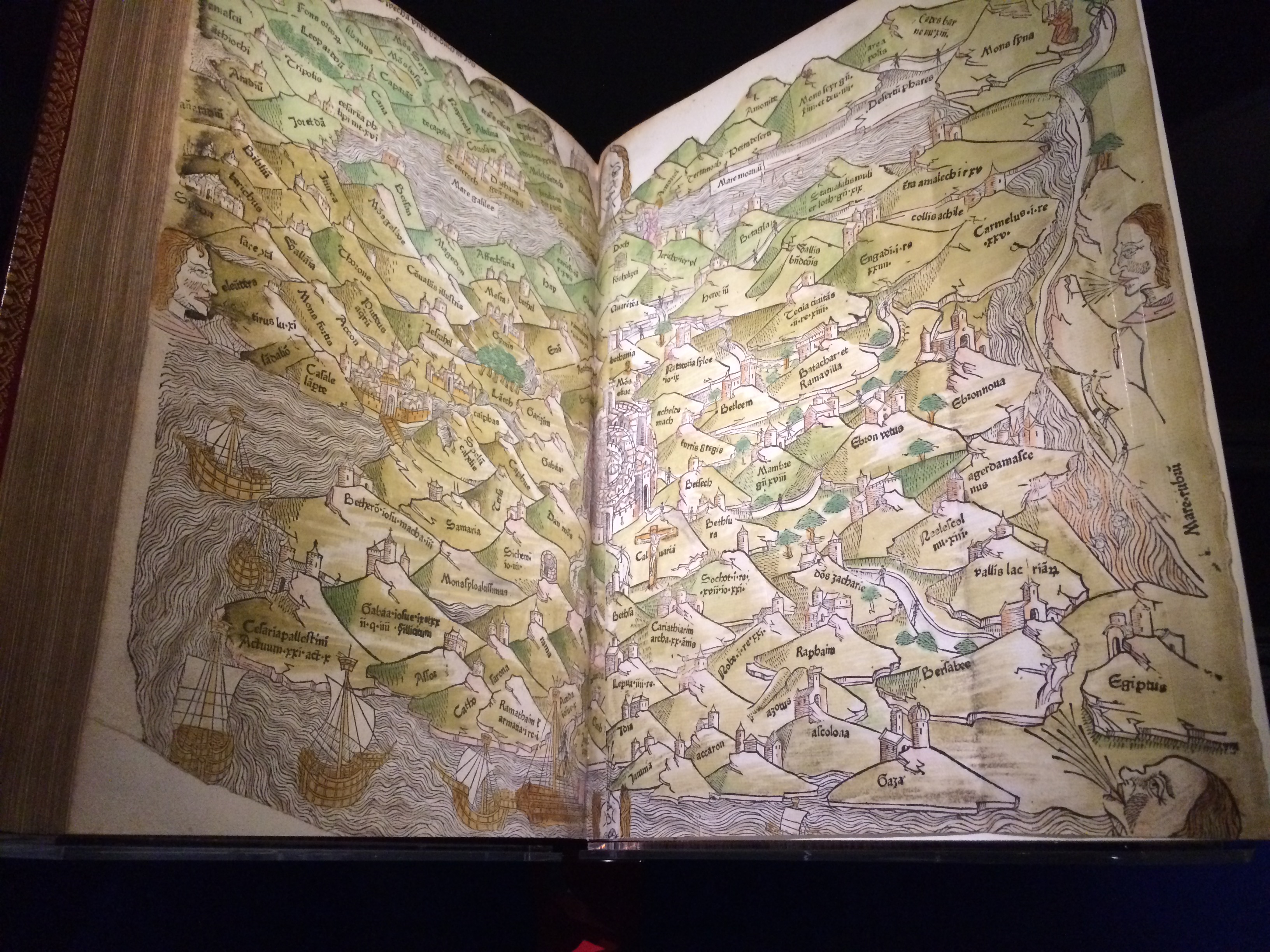

There was one with a colored map of the Holy Land in the endpapers.

I and 30 elderly women listened to a gallery talk about one of the first editions of “The Canterbury Tales,” sitting on stools in the dark around the dramatically lit book.

I then went across the road, under an arch, through a cloister and up two flights of stairs to the part of the Hunterian where historical and natural objects are displayed,

There was a hall reminiscent of so many in natural history museums. This one featured a plesiosaur.

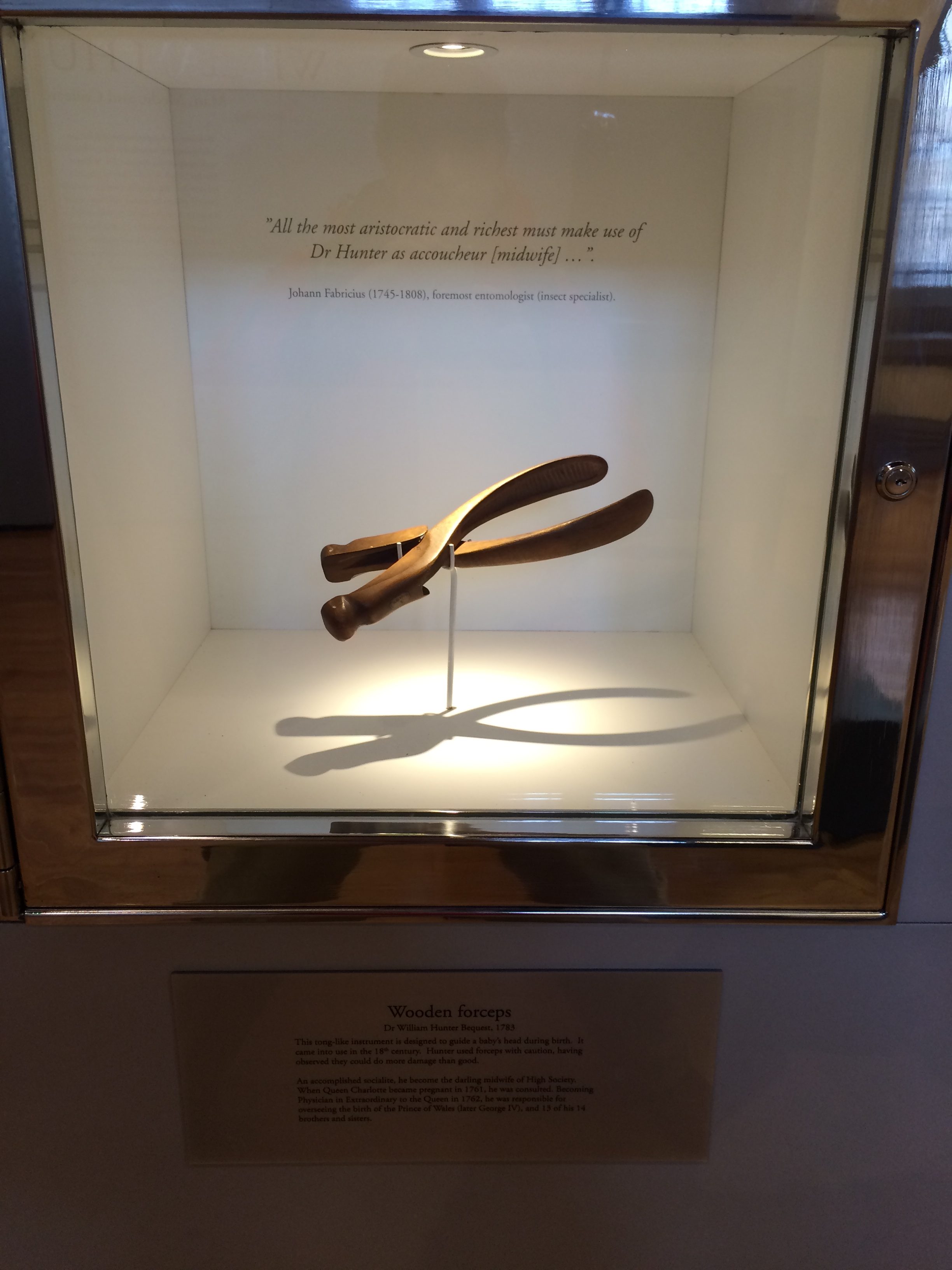

Hunter’s wooden obstetrical forceps (an instrument he apparently thought was overused) was on display.

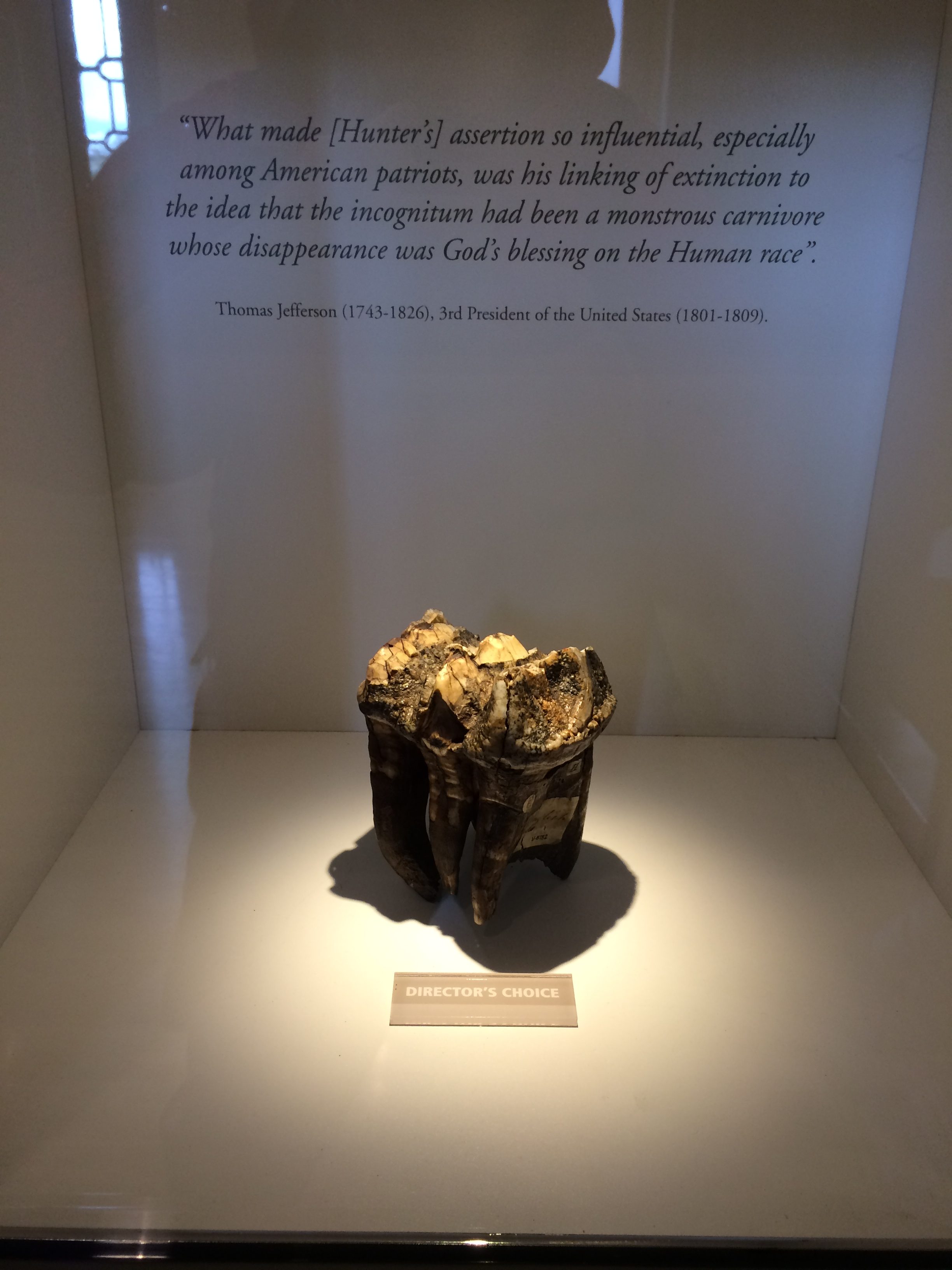

As was a mastodon tooth he collected. The quotation behind it is from Thomas Jefferson, another polymath.

As with the books, these objects were beautifully bracketed and illuminated, an art in itself.

Nearby was a case containing relics from a dig at the Antonine Wall, a Roman wall built in AD 142 from turf on a stone base. It’s a northern version of Hadrian’s Wall, spanning 40 miles at the waist of Scotland. One of the things found was a rusted but still recognizable pair of sheep shears, a foreshadowing of the future of the Highlands.

Nearby, unbelievably, was the remnant of a leather tent and tent pegs.

Which reminded me: It was time to go camping.

Recent Comments