I arrived at the Park House B&B in the light rain after 17.7 miles of walking, my longest day. It was supposed to be a 12.1 mile day, based on the GPS route I’d booked months ago. But I tried to be smarter than my winter plans.

I attempted to take an abandoned railroad bridge over a river, which would have cut miles from my route. The bridge was blocked and the gate was topped with spikes. I’d gotten there by slogging through fields and around bits of narrow road. I could have gotten around the barricade, I decided, but then there would be another one at the far end. If I couldn’t get over that I’d have to retraced my steps, get over the first barricade, and return to the original route.

I decided on discretion. I slogged back through the fields and farm tracks and went up the paved road—as originally planned—and crossed the river at the bridge that cars and everyone else takes.

The Park House B&B was poorly marked. I stopped and asked a man named Allan for directions. His dog was yapping in the car. Allan consulted his phone; mine was out of power.

The B&B was up a dirt road. I was glad to get there.

The proprietress is Madeleine Braithwaite-Exley. She and her husband have three boys, all grown and out of the house. Her husband, Marcus, is a retired infantry officer who served in Northern Ireland, the Falklands, Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan. He was away, tending to an ill relative.

Madeleine comes from a family with deep military roots. Her father was in Normandy on D-day+3. Her maternal grandfather served in both World War I and World War II. The next morning she told me about him.

His name was Maurice Wilson. He was born in 1899. His brother was killed in the Battle of La Bassee, in October 1914, one of the first engagements of the Great War. Maurice’s mother was determined Maurice not fight, but as soon as he was old enough he volunteered, catching the end of that catastrophe.

Madeleine didn’t know much about his service in that war. But she did about his time in World War II. She got out a scrapbook.

He was a career soldier, in middle age, when the war began. He was a member of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, part of the 51st Highland Division. Here he is before the war, second from the right.

The 51st Highland Division was part of the British Expeditionary Force sent to France to help defend it against German invasion. The division was fighting the German army and retreating toward Le Havre when 338,000 other members of the BEF were evacuated from Dunkirk.

The 51st Highland Division’s ironically named commander, Major General Victor Fortune, requested evacuation too. Winston Churchill refused, believing that some British soldiers should remain and show solidarity with French forces. Within days, however, France fell. The division surrendered at Saint-Valery-en-Caux in June 1940, and 10,000 Scottish soldiers were taken prisoner.

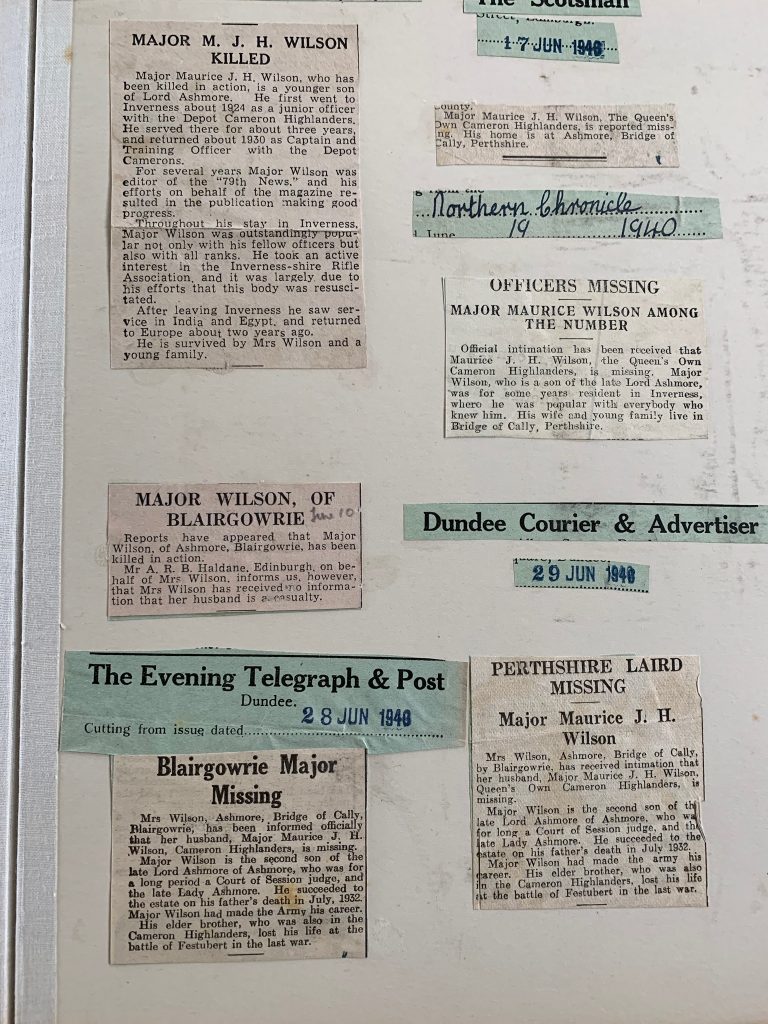

Major Wilson was initially reported as killed–a fact that, astonishingly, was reported in a dependent clause in the lede of the newspaper story. Soon, that report was changed and he was said to be missing, not dead.

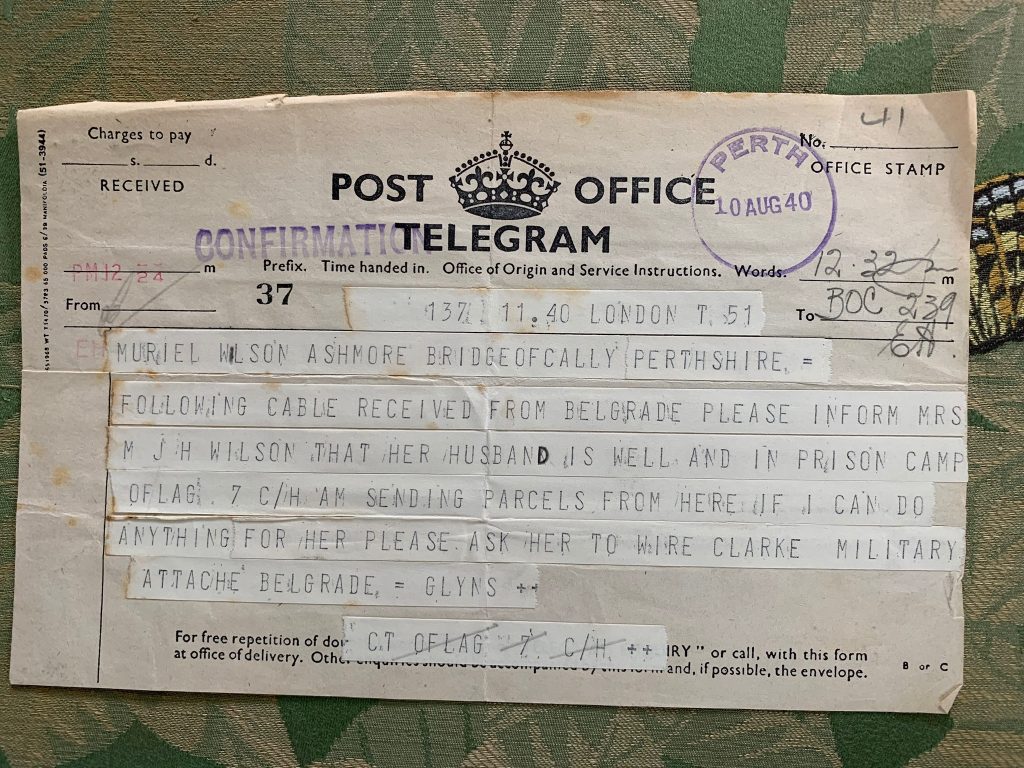

Finally, in August, his wife got a telegram saying that he was alive in a German prisoner-of-war camp, Oflag 7.

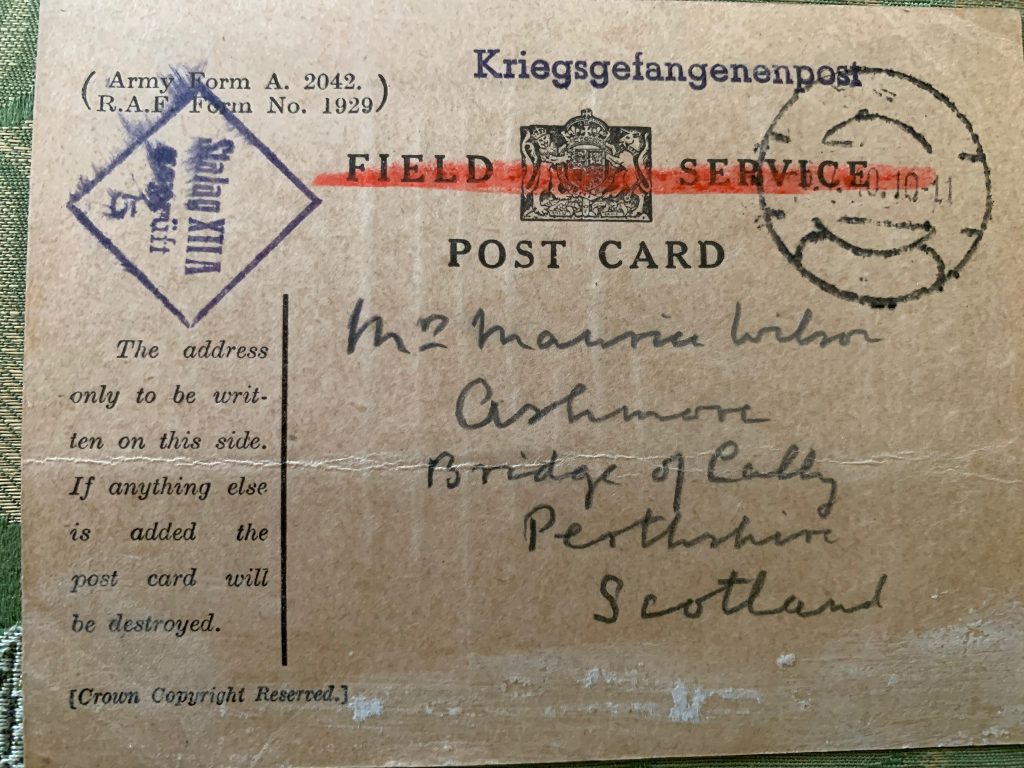

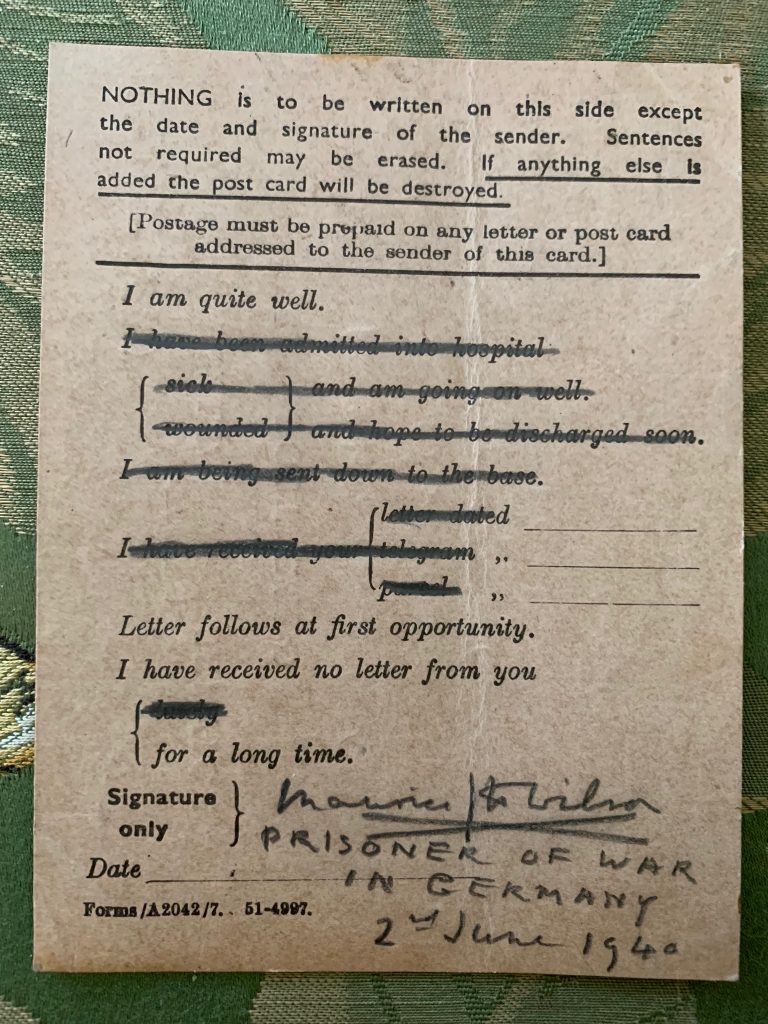

The first contact was a postcard that provided a menu of statements. If they weren’t true they had to be crossed out. Of the three that remained on Maurice Wilson’s, one was: “I have received no letter from you for a long time.” Madeleine’s voice caught as she read that.

Eventually, letters were sent and received. As an officer, Major Wilson had a responsibility to keep up the morale of his fellow prisoners as much as he could. He recited poetry, organized dances and musical events, and chess tournaments.

In the meantime, his wife had invited several war widows and other wives of prisoners to move to her estate, Ashmore, with their children, away from cities that were bombing targets. They lived on what the farm grew and war-time rations, and also ran a small school. Although the family was wealthy, life was hard and self-reliance was the order of the day, Madeleine said.

“What was stress? Nobody knew what stress was. Stress was something you put on a rope.”

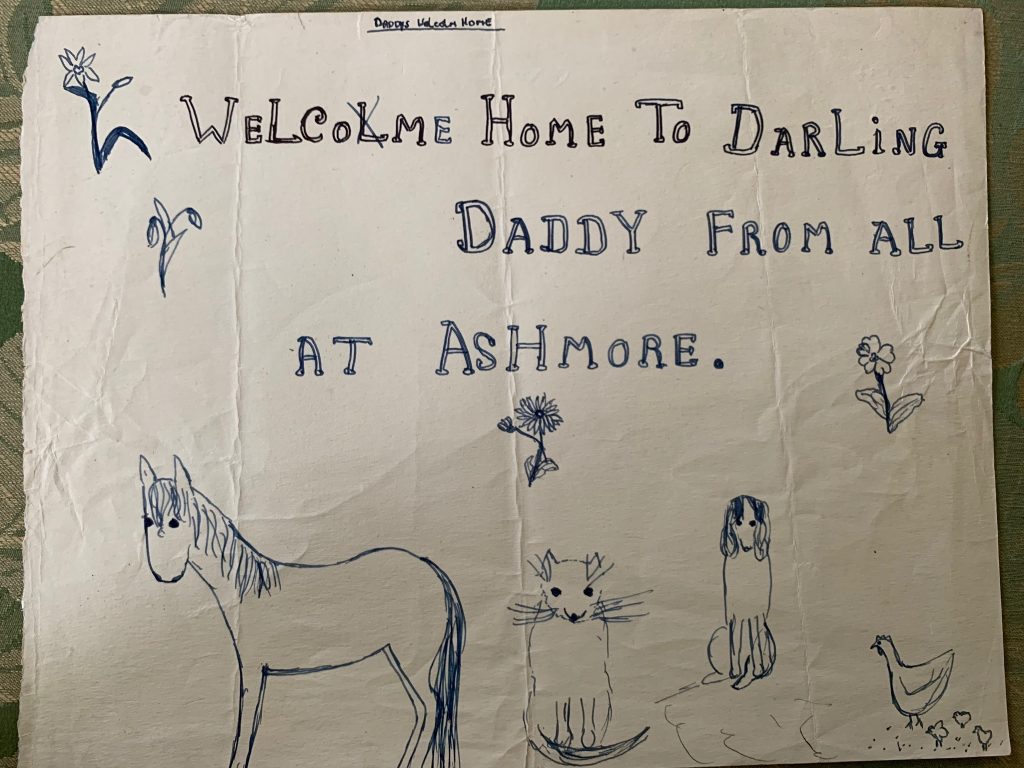

Major Wilson asked his wife to have the children in the school write to the prisoners and tell them what was happening on the farm so that they would have a sense of the world outside prison wire.

“My grandfather used to say: ‘I have 40 years of good memories, and of a wife and four children. But I am in command of young men who were captured at 18 and 19, and they have no such memories to sustain them’.”

Major Wilson was a prisoner for five years.

His daughter, Madeleine’s mother, spent the end of the war, when she was 17 or 18, in the Women’s Royal Naval Service (the “Wrens”) in the Orkney Islands, doing clerical work at a huge naval base in the Scapa Flow. When her father returned on a POW ship in 1945, she went in uniform to Portsmouth to meet him. They didn’t recognize each other.

The children on the farm wrote a note from the animals, welcoming him home.

Maurice Wilson stayed in the Army until 1955. Here he is with Madeleine’s mother next to him.

He died when Madeleine was about 14. I asked her if he seemed damaged by the war in any obvious way.

“He lived very happily. He wasn’t so traumatized that he couldn’t come and be a dad again.” She paused and thought, and then added, “He would cry at anything. He was very emotional. He cried at good news.”

Such great great photos. In the previous post, I loved that line about “undertone of absence.” Speaking of which — 5 years as a POW! Hard to imagine.

Everyone has a story, and the wonderful thing about you, Dave, is that you always find time to ask and listen.