Among the many holes in my education is any formal instruction in geology.

You’d think that geology would be an unavoidable subject like algebra, biology, and American history, force-fed to even the reluctant student. After all, every one of us lives in a physical environment (no matter how altered by man) of dirt, rock, water, and altitude, and for some also hills, mountains, valleys, rivers, swamps, bays, and oceans. Why isn’t knowing their stories mandatory?

The answer, probably, is that we can deduce without help what seems like an adequate amount of knowledge. Water flows downhill, evaporates, and changes with the season. Some mountains are rocky and others are covered with vegetation, and that has something to do with weather. Dirt is darker, deeper, and more fertile in some places than in others.

Learning some geology (beyond a little reading of John McPhee) would have immeasurably enriched my time outdoors, especially on camping trips that I began taking as a child. It seems too late now–except that I was in my 30s when I learned enough chemistry to have it immeasurably enrich my understanding of the kitchen, liquor cabinet, and utility closet. So, maybe it isn’t too late.

What’s certain is that few experiences make you face geology and wonder about it more than a trip down a canyon. Wondering about it doesn’t get you very far, but facing it provides endless entertainment and surprise.

A mile into our second day the topography changed. Now, there were rock walls on both sides of the river.

The first walls we saw were red-ochre sandstone. In places dark drips colored them like Morris Louis paintings. Occasionally the stains were white–calcium salts, I guessed. Great expanses were covered with “desert varnish”–iron and manganese oxides formed by “the interaction of airborne dust and microscopic plants upon exposed rock under moist conditions,” our Canyonlands River Guide informed us. At certain angles they shimmered.

Sedimentation, erosion, and time are what made this part of the world.

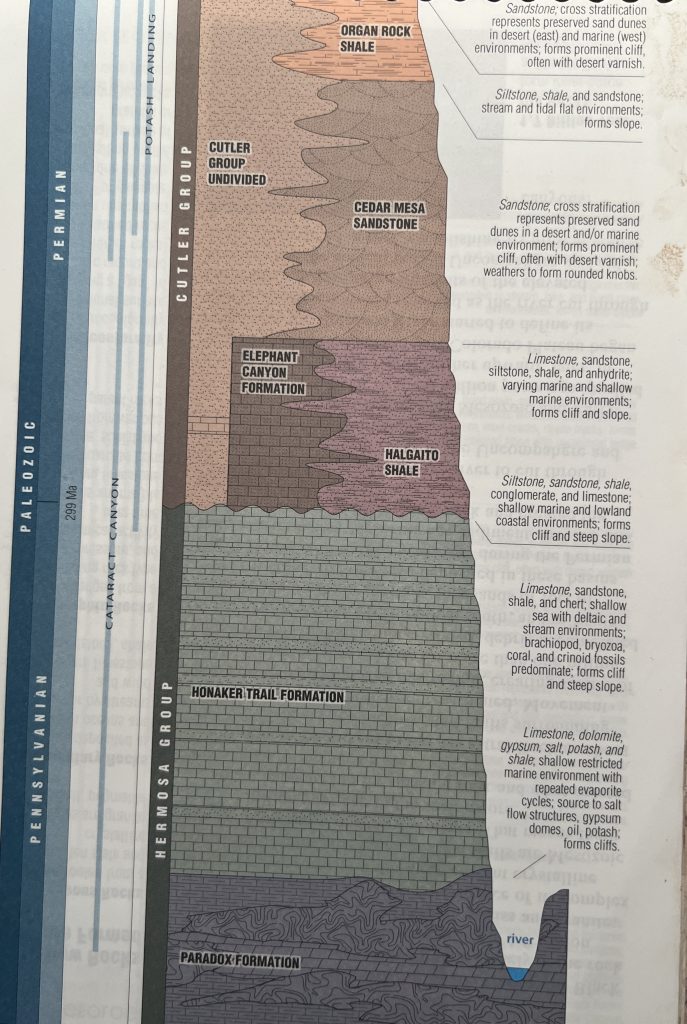

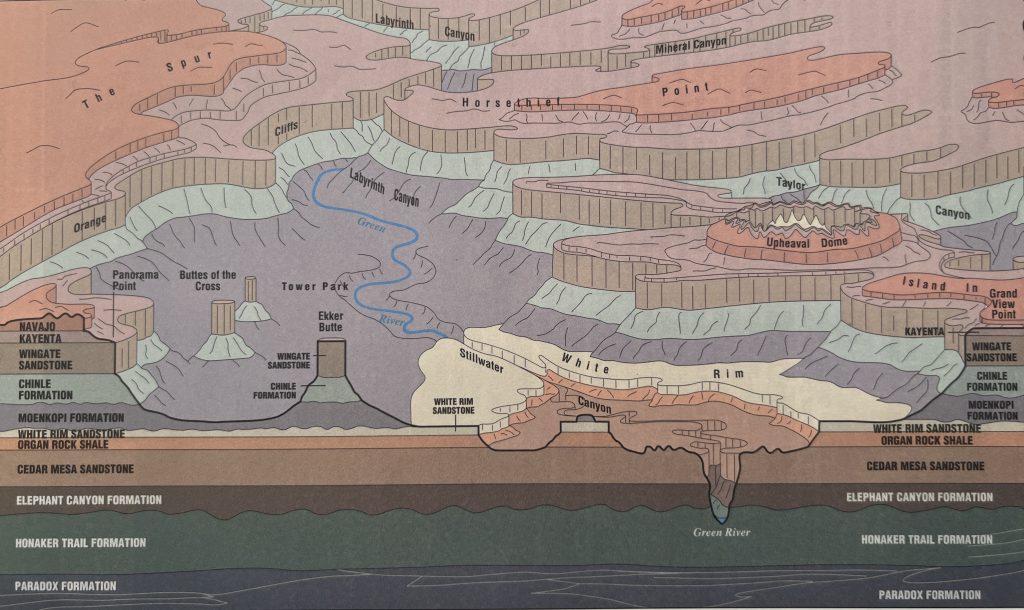

Over the length of the trip, nearly two dozen formations and named strata, created between 300 million and 140 million years ago, were on display.

The river guide dutifully informed us at what mile a certain formation first appears, but this was often hard for the uneducated eye to discern. Sometimes a stratum appeared, disappeared, and then reappeared farther downstream. Here’s a schematic of the Green River’s streamside geology as it travels through Labyrinth and Stillwater canyons.

The great chronicler of these canyons is John Wesley Powell, who led an expedition down the Green and Colorado Rivers in 1869–the first recorded group to do so in one trip.

Powell was a geologist, geographer, and ethnologist as well as an explorer. Equally important, he was a felicitous writer. Decades after that trip, he wrote a popular account based on a journal he kept while it was underway. “The Exploration of the Colorado River and its Canyons” (1895) captures the wonder that canyon country inspires in those for whom it’s new.

I climb the cliffs and walk back among the strangely carved rocks of the Green River bad lands . . . Barren desolation is stretched before me; and yet there is a beauty in the scene. The fantastic carvings, imitating architectural forms and suggesting rude but weird statuary, with the bright and varied colors of the rocks, conspire to make a scene such as the dweller in verdure-clad hills can scarcely appreciate.

Unfortunately, neither Larry nor I had a fraction of Powell’s knowledge of geology. But we could observe, admire, and imagine as he did.

Occasionally you can get close enough to inspect the seam between different layers of rock. This greenish one may be the Chinle Formation, which the guide describes as “shale, siltstone, sandstone, conglomerate, and limestone.”

Here softer rock has crumbled into a hoop skirt, hemmed in tamarisk and wrapped around a stout body.

I call this “Priap’s Gate.”

Here’s a bald eagle perched with its back to the river.

The wonderful thing in the canyons, however, is that a just-as-interesting world exists in miniature if you get off the river and climb inland.

I did that one afternoon after we pitched camp. Our campsite was already in shade by the time I set out. We were next to the western wall of the canyon, the sun still visible but falling fast. Across the river, the top half of the canyon was still in the sun. A curtain of yellow light was rising up the wall and soon only the rim would be illuminated.

(Powell had a good eye for the sun’s daily drama in canyons, writing that “the heights are made higher and the depths deeper by the glamour and witchery of light and shade.”)

The wall on my side of the river was being excavated into an amphitheater by water periodically coming over the rim–or so I deduced. The slope was fine sand, sparse vegetation, and a jumble of boulders and fallen ledge. The walking was neither easy nor dangerous. My destination was a layer of magenta rock below the red sandstone that appeared to be everything above it.

I got there. The rock was less magenta that it appeared from below. There was no way to climb onto it without a lot of time and effort, neither of which I had. But that didn’t matter; the journey not the arrival matters.

Everything around me was in a state of generous revelation. It was art, and I was the only person in the gallery.

Pieces of the rock wall were peeling, with little obvious reason. Up close, the grain wasn’t uniform; it had layers of slightly different shade running through it. In places, the wall was full of holes made by the elements playing on weaknesses in its lithic genes (or so I again deduced).

I was observing a miniature of the world we were paddling through.

The downhill side of one fallen boulder was carved into what looked like a 3-D topographic map or a satellite view from space–a lesson in contour and weathering for those who’d missed it elsewhere. I was reminded of the advice offered by Leonardo da Vinci to “seek familiar forms in unfamiliar places.”

I saw life, too. A lizard darted up a stone, stopped until its brain caught up, and then took off again.

Presiding over everything was a juniper tree, standing alone in the slope of mineral debris, healthy and seemingly proud to represent large plant life.

I could smell it as I approached. The berries at the ends of its branches were covered in the waxy dust–“bloom”–that helps protect them from drying out. Their plumpness seemed a kind of defiance. I picked one, squeezed it without breaking the skin, and juniper essence filled the air.

I picked five more and put them in my pocket. You’re not supposed to take anything out of the canyon, but I made an exception for them.

Recent Comments