From The Washington Post, September 30, 2022

Some cities have a past that is beautiful in the present. Old buildings and public spaces effortlessly become tourist attractions long after their reason for being has disappeared. Venice is like that. So is Paris.

Other cities carry their past into the present as an unavoidable burden, sprucing up their edges with beautiful things, new and old, to distract attention. Dundee, on the east coast of Scotland, is one of those. So is Baltimore, my home.

I spent most of a week in Dundee last spring while doing archival research in St. Andrews, 13 miles to the south across the River Tay, Scotland’s longest river. Every day I commuted to my hotel — 40 minutes by bus — in a “real” city, as I had between Washington and Baltimore for 22 years.

And I came away a fan. More than a fan, actually. When I left, in my breast was the defensive love felt by people who stumble into has-been cities and stay, as I’ve done in Baltimore for more than half my life.

Dundee, like Baltimore, is a city whose great days are a century gone.

It has a world-class industrial past, and a vast inventory of vacant industrial buildings in the present — like Baltimore. Both cities have a dominant and oppressive building material — red brick in Baltimore, and in Dundee a local sandstone that can’t make up its mind whether it’s tan or gray. As in Baltimore, some of these buildings — wonderful ones — have been repurposed, like the hotel I stayed in, an old linen mill.

Both cities have signature culinary products — crabs in Baltimore and marmalade in Dundee. Both have a lot of litter. Both are defaced or decorated with graffiti, depending on your taste. Dundee has the highest crime rate of cities in Scotland while Baltimore ranks third in the United States.

Where does one begin to learn about Dundee’s history and heart? Luckily, for a tourist, there is a place.

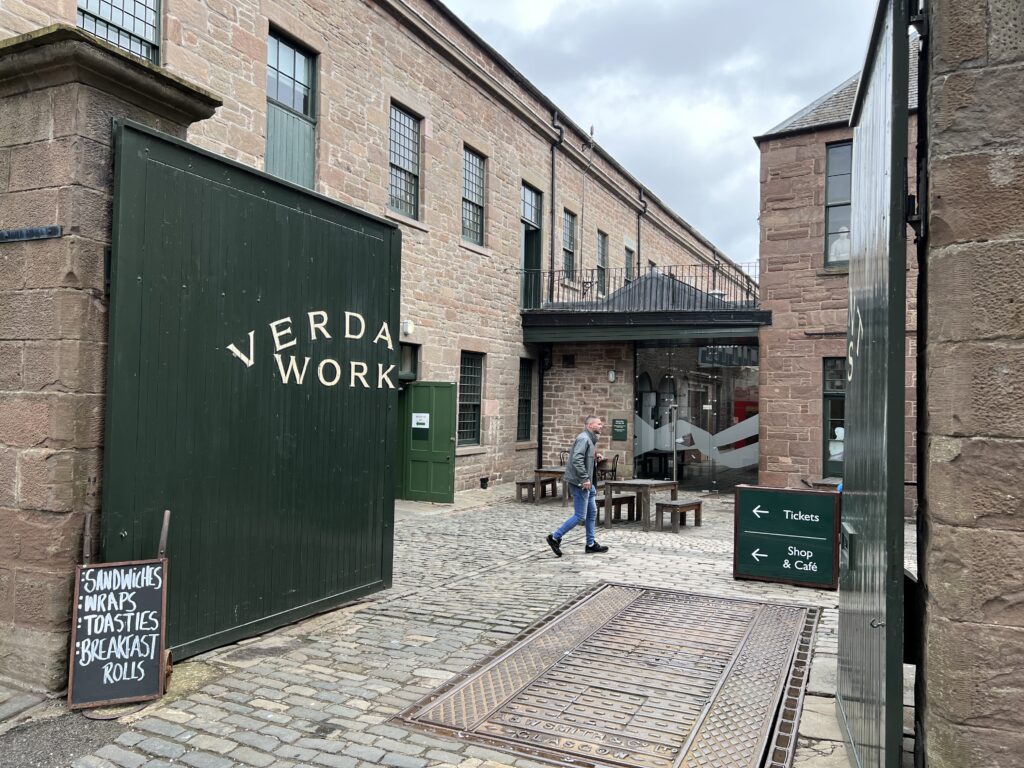

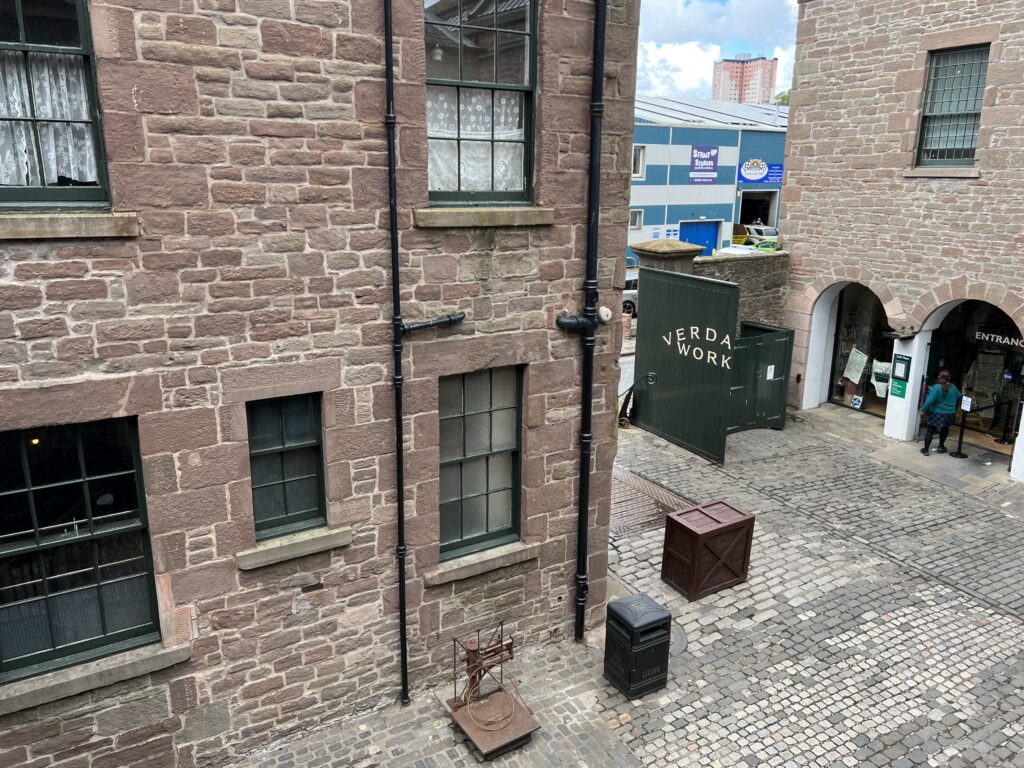

It’s called Verdant Works, a former jute mill in a part of the city known as Blackness. (Dickens couldn’t have come up with a better name.) Once the employer of 500 people, the mill is a keyhole through which most of Dundee’s history can be descried. Unlike many factory museums, its story is made vivid by docents only one or two generations removed from its inescapable clutches.

But before we spend an afternoon there, let’s look around.

A vibrant maritime history

Dundee is a port on the Firth of Tay, the place where the river widens into a tidal estuary before entering the North Sea. It was built on trade, and for many centuries it was Scotland’s second most important city, behind Edinburgh. Its maritime past is telegraphed in street names (Chandlers Lane, East Whale Lane), stone workshops along the waterfront, a compact Maritime Trail where its piers and shipyards once stood, and a small collection of historic ships.

Of the last, the most notable is the Discovery, a three-masted sailing vessel that also had a steam engine. Billed as the first ship designed specifically for scientific research — there was no iron or steel within a 30-foot radius of its “magnetic observatory” — it was built in Dundee in 1901 and owned by the Royal Geographical Society.

The Discovery’s most famous voyage was a four-year trip to Antarctica featuring two of Britain’s legendary explorers — Robert Falcon Scott, the captain, and Ernest Shackleton, the third officer. Visitors are allowed to go almost anywhere on it. (In that regard it’s better than Baltimore’s estimable Constellation, built in 1854 and used to catch slave traders, among other tasks.)

On the pier next to it is V&A Dundee, an offspring of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Like its parent, it’s dedicated to design, decorative arts and performance. Opened in 2018, the V&A is the antithesis of Discovery — no vertical lines in view, and clad in what looks like a grate from a pier. But it’s just as interesting, with a wonderful collection that includes a salvaged tea room from Glasgow that was designed by Scotland’s art nouveau genius, Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

The ship and the museum are the most visible pieces of a 30-year, nearly $2 billion development project along five miles of waterfront.

A 15-minute walk inland is the McManus, a gallery and museum that’s a good place to see art and artifact telling Dundee’s story. That includes eras as Britain’s most important whaling port; a textile and shipbuilding center; and, in the second half of the 20th century, the British home to American companies, including Timex and National Cash Register.

As in Baltimore, Dundee’s shipyards and factories eventually closed. (The city lost 10,000 manufacturing jobs in the 1980s.) Like Baltimore, it’s now trying to cobble a future out of tourism, biotech and lots of little companies.

There’s a lot to see in Dundee’s environs, including castles and archaeological sites. But if you have time for only one stop, make it Verdant Works. The museum stands in for the more than 100 jute mills that once operated in Dundee and employed, by the late 1800s, 40,000 of the city’s 170,000 residents.

The jute era

Jute?

It’s a fiber made from the middle layer of a 12-foot-high grass that grows mostly in India and Bangladesh. Its closest competitor is hemp.

You make burlap from jute. From burlap (in the old days) you made the binding of cotton bales and sacks for coffee, cocoa, sugar, potatoes and lots of other things. Woven tighter, it became cloth for tents and the covers for artillery pieces. War was good business for jute. In one two-week period during World War I, 150 million jute sandbags were shipped out of Dundee.

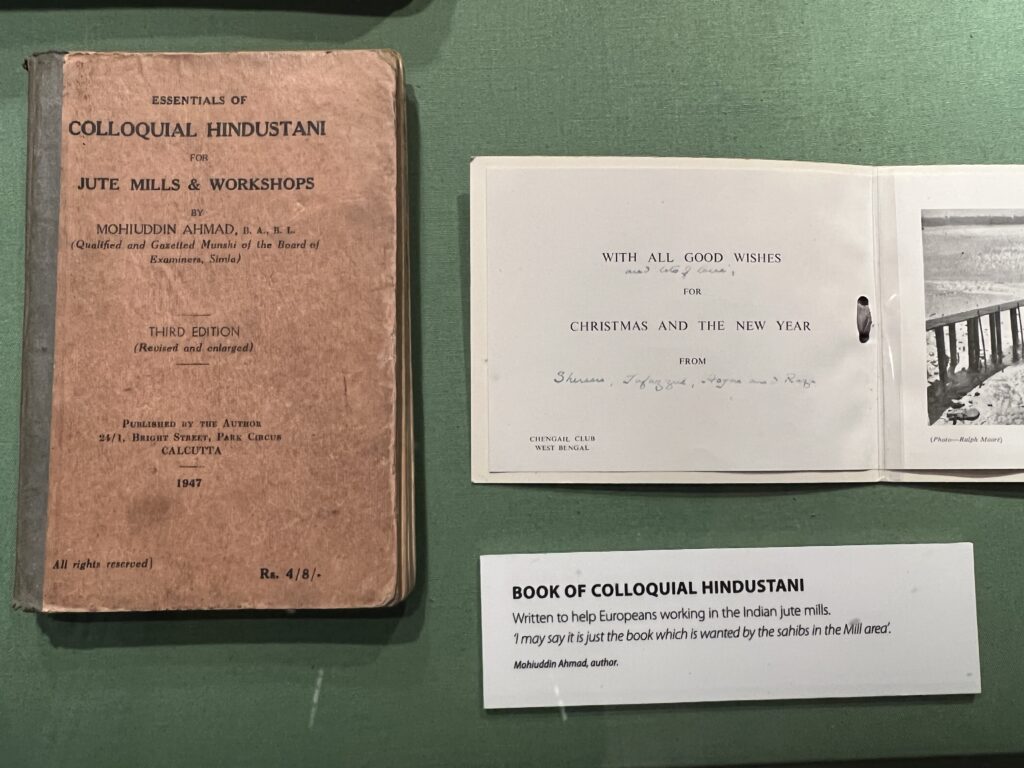

So how did a city on the North Sea come to process fiber grown in South Asia?

In the 1700s, Dundee developed a linen industry, importing flax from the Baltic states and other high-latitude countries where it grew. By 1840, the city had overtaken Leeds, in England, in the production of coarse linen. The Crimean War (1853-1856), however, interrupted the flax trade.

Dundee’s industrialists realized they had the knowledge and labor to process, spin and weave other fibers. Imperial Britain had access to a flax alternative growing in its colony, India. Add a little time and Dundee became the jute capital of the world.

A small thing that made a big difference was Dundee’s whaling fleet. At some point the mill managers discovered that washing the raw fiber in a mixture of 90 percent water and 10 percent whale oil made raw jute less likely to snag in fast-moving machinery. This 10 percent solution was enough to keep Dundee’s whaling industry alive 50 years longer than in almost anywhere else in the world.

‘Only show in town’

The first docent I encountered at Verdant Works was Ian Findlay, a 73-year-old retired civil servant. His mother’s mother was a jute weaver. His father’s mother was a jute spinner. His father’s father was a maintenance engineer in a jute mill.

“It was the only show in town, to be honest,” he said.

On the factory floor I met another man, Iain Sword, also 73, whose jute pedigree wasn’t as long. His father left school at 14 and was a jute salesman, mostly to the carpet industry, his whole life.

Sword had been a banker around the United Kingdom before retiring to Dundee, his hometown. He was a jute Wikipedia, and no apologist for the mill owners. He told me that when Britain finally required public education, Dundee mill owners successfully petitioned to be an exception. They got permission to employ “half-timers” — children who’d work 30 hours a week in the mill for minuscule pay and go to school for half days only. They were so good at crawling under machinery and pulling out dust and fibers!

In fact, 70 percent of mill workers in Dundee were women and children, who were paid less than men. The city was known as “She Town” and was the first place in Scotland where jailed “suffragettes” went on hunger strike. It was also full of men raising children and drinking too much.

In part as a consequence of these conditions, 63 percent of Dundee’s eligible men fought in World War I, where they were slaughtered in droves. A battalion known as “Dundee’s Own” sent 423 men and 20 officers into battle at Loos, France, in September 1915. All but one of the officers were killed, as were 230 enlisted men. The McManus has a spectacular painting of two dozen Dundonians — that’s what the city’s residents are called — standing in the ruined landscape after another battle, Neuve Chapelle. The painter, Joseph Gray (1890-1962), had been a newspaper artist in Dundee; everyone in the painting is identified.

“Working conditions were just very, very hard. It’s very difficult to think of what life was like,” Sword said, between explanations of how various pieces of machinery operated.

A glimpse of that life, however, comes through in a remarkable piece of public health research published by the Royal Society of London in 1886. The authors were three men — Dundee’s health officer; a chemist at University College in London; and a second scientist from that institution, J.S. Haldane, who would become the most important respiratory physiologist of his generation.

The team took air samples from tenements occupied by mill families — 29 one-bedroom and 13 two-bedroom dwellings — and from 18 dwellings of four or more bedrooms occupied by middle- and upper-class families. They measured temperature, carbon dioxide (a product of respiration and a measure of crowding), as well as “organic matter” (basically dust), and bacteria and mold.

“The samples were taken during the night, between 12.30 A.M. and 4.30 A.M.,” the scientists wrote. “The houses were visited without warning of any kind to the inhabitants, so as to avoid the risk of having rooms specially ventilated in preparation for our visit. In every case but one we were most civilly received.”

The average number of sleepers per room in the one-room flats was 6.6; in the two-room ones, 6.8; and in the houses of four or more rooms, 1.3.

At 52 pages, it’s a long and complicated study that highlights the dramatic effects of crowding. Compared with four-room houses, one-room ones had air with twice as much carbon dioxide, four times as much dust and seven times as many microorganisms.

The most important data, however, was provided by Dundee’s health officer.

The death rate of children was four times higher in one-room tenements than in four-room houses. Residents living in one room “have the chance at birth of living only one-half as long as those in better-class houses, or they die nearly 20 years sooner, on the average, than those of the better class.” At this the scientists couldn’t restrain themselves: “This is an enormous difference.”

Other research found that teenage boy mill workers were 4½ inches shorter and “a stone lighter” — that’s 14 pounds — than rural teenagers in Scotland.

Haldane’s more famous son, mathematician and geneticist J.B.S. Haldane, later said of his father: “His experience of the Dundee slums may not have made him a radical, but it kept him one.”

What Dundee needs is its version of New York’s Tenement Museum, or even Baltimore’s modest Irish Railroad Workers Museum, to bring these conditions to life.

The jobs leave

Jute mill owners eventually found a way to make even more money: They moved the business to India, closer to the fiber’s source. Dundee lost a whole industry, much of its culture and untold thousands of people. Before, it had been a place where a boy with mechanical aptitude could advance — even if he left school at 14. “The loss of the textile industry pretty much led to the loss of all that,” Iain Sword told me.

But remnants of the jute trade are still visible in Dundee, if you keep an eye out. Passing a trash-strewn factory yard early in my visit, I saw at the far end a sign over a door: “Drivers should not stand under slings while bales are being hoisted.” Jute bales — compressed rock-hard to save space on shipment from India — weigh 400 pounds.

The city is also full of concert halls, parks, pools and other public amenities that might not exist but for the barons. They gave generously while mercilessly exploiting their workers — like Andrew Carnegie, a Scot whose wealth paid for more than 1,500 libraries in the United States.

Verdant Works shows this story and doesn’t just tell it. The exhibits are clever and moving. Physical objects butt up against photographs of people doing work with those same objects. You feel as if you’re in a diorama or onstage in a play. Mural-size photographs make faces larger than life. You can’t help pondering the individuality of the people staring at you.

It’s a place to feel the beating heart, and the stony heart, of a city.

Recent Comments