I have dug up some information about a distant relative, Sydney Arthur Row, that may be of interest to some of you.

Sydney Row (1897-1970) was my father’s cousin. His father, John Row, was the older brother of my father’s mother—Etheldreda Row Brown. The Rows were English Canadians who emigrated from southern England to Montreal, and later moved to Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Sydney Row and his brother (also named John, but called Jack) were World War I veterans of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Syd enlisted on October 29, 1914 and was discharged February 18, 1919. His brother, who enlisted two days before him, miraculously also survived the war.

Syd moved to Framingham after trying farming in Saskatchewan with Jack after the war. He lived with my father’s family on State Street for six years, working as a mechanic at Dennison Manufacturing Co., and later as a salesman for the Simmons Bedding Co. He brought youth and energy to a house full of old people. My father’s father was born in 1863, and his bachelor uncle, who also lived with them, was even older.

I knew that Syd Row—whom I met several times as a child—and his brother had been in World War I. What I learned recently was that a another brother, Frank, and their father, John—a pharmacist assigned to a medical attachment—were also in uniform.

The government of Canada has made most of the military records of its veterans publicly available, and has collected supplementary information from survivors, as well. The latter includes letters from World War I veterans to family members, and to each other. The Row family, with whom I’m not in touch, obviously provided copies of letters to this archive.

Sydney and Jack were both born in Whitewood, Northwest Territories.

This is a photograph of Sydney at age 17 or 18. The photographic paper has sketches of airplanes and boats around the portrait oval, and the printed message “I’m on my way.” This suggests that Forde Photo Studio on Main Street in Winnipeg made lots of pre-deployment pictures like this.

This is Jack Row about the same time.

On May 9, 1918, Jack Row wrote a letter to his mother in which he handicapped each family member’s chance of surviving. It’s an extraordinary exercise in fatalism masquerading as reassurance.

At the time, Jack was 22 and recovering from a wound in England. He noted that “my left arm is not as strong as my right and a little awkward but I can handle a machine gun as good as ever.” Syd, 20, was also recovering from a wound. Their younger brother Frank, recently mobilized, was 19. Their father was about to turn 52. The other two people mentioned in the letter are younger children—Bessie, 16, and Philip, 13.

(“Blighty” refers to a wound and a place where one recuperates from a wound.)

There are four of us in the army, three of us front line men. We have never hunted for soft jobs and have been in as hot corner as any men in France yet we pulled through, two of us with honours . . .

If I go up the line I have a ten to one chance of getting a nice Blighty like I got last time . . .

Syd was marked D(1) when I left Blighty, which means six weeks gymnastics or “jerks” as it’s called . . . . Dad is under shell fire but never goes into the line except at night or any emergency as he is in charge of a water squad of twelve men to test the water which is supplied to the front line and reserves. If anything comes off he becomes a member of the Field Ambulance for duty.

Frank is a brigade runner so he is not likely to be any less than a mile from the front line, so he has twice as good a chance as last summer when they were in and over the top most of the time. I stand a better chance than him with the machine gun. We dig in and don’t move or fire till Fritz is actually coming over. Frank as a company runner had to go through all the shelling, often over the open ground, dodging here and there and Syd was the same but still they came through.

So dear you are bound to have some of us come through all right and believe me this war has made us all more united and after this if one Row is in it the rest are with him.

Bessie seems to have grown into a fine girl and Phil will never be old enough to join so cheer up and never mind.

Love to all, Jack

One of the “honours” Jack Row mentions in the letter is a decoration that Syd had won.

My father knew that Syd had been a trench runner and had seen a medal in his room in Framingham, but knew nothing about how he’d won it. He didn’t ask. Years later, he wrote: “Sydney rarely mentioned the war. I was warned by my parents to not press him about this phase of his life unless he brought up the subject.”

A number of years ago I got a copy of Syd’s military records. The records noted the award, but provided no details, and I didn’t pursue the matter. Recently—inspired, in part by Peter Jackson’s documentary “They Shall Not Grow Old”—I got out the records again and decided to dig deeper.

It turns out the name of the decoration was the Military Medal, which I’d assumed was a generic description. He’d been awarded it on February 14, 1918. The Military Medal was a decoration given to men in Britain and Commonwealth nations below commissioned rank. Approximately 424,000 Canadians served overseas in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in World War 1, and 12,345 got the decoration.

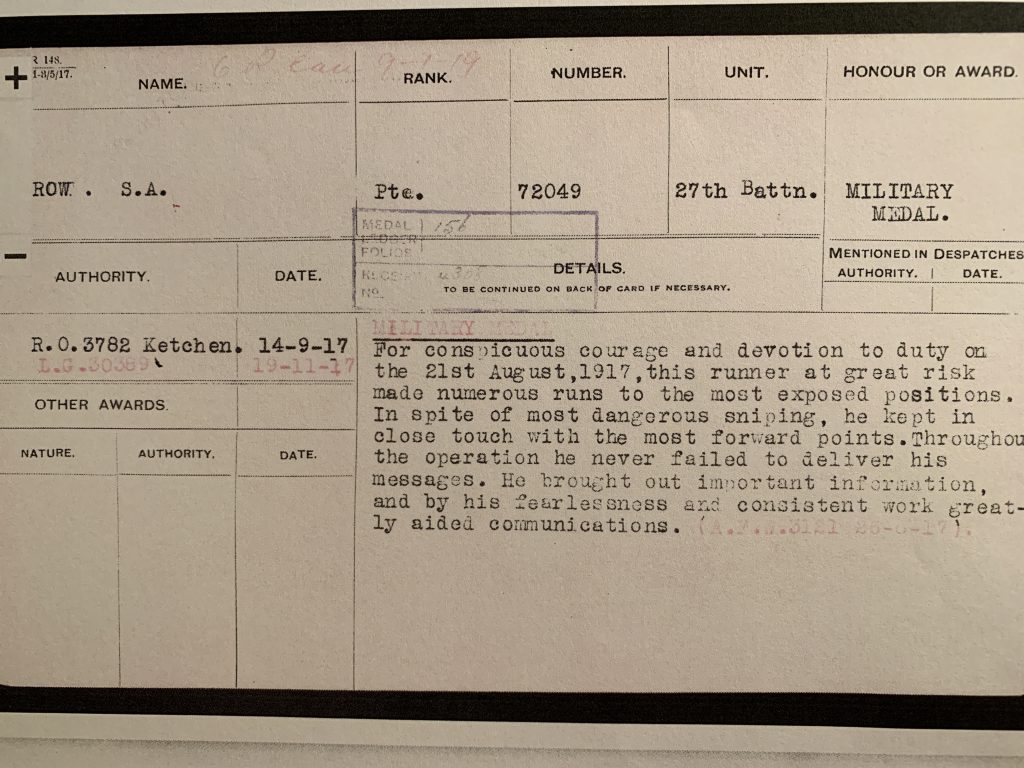

With help from people at the Canadian Expeditionary Force Study Group–an online list-serve and chatroom about Canada’s role in the Great War–I found the citation for Syd’s Military Medal. It read:

For conspicuous courage and devotion to duty on the 21st August, 1917, this runner at great risk made numerous runs to the most exposed positions. In spite of most dangerous sniping, he kept in close touch with the most forward points. Throughout the operation he never failed to deliver his messages. He brought out important information, and by his fearlessness and consistent work greatly aided communications.

Syd was 5-feet, 7-inches, and 125 pounds when he joined up, so he had the body type for the job. Interestingly, on his discharge physicals he was listed as 5’9″ and 5’10” and 155 pounds. Both weight-gain and height-growth were common after enlistment, according “They Shall Not Grow Old.”

The battle was not Vimy Ridge, as my father had thought, but Hill 70. (There’s a long article about it in Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Hill 70.) On August 21, the day Syd earned the medal, Canadian troops were taking the town of Lens in urban combat, which was rare in World War 1.

I suspect Sydney Row won the award not for running between trenches or in trenches, but for running through streets and plazas to buildings where soldiers were holed up. That would explain the reference to sniper fire in the citation. On that day, the Canadians lost 1,154 soldiers.

Syd was proud of the decoration. People awarded the Military Medal are permitted to use the “post-nominal” MM after their names. On his discharge papers, Sydney Row signed “SA Row MM.” Whether he used it after that I don’t know.

Both Syd and Jack stopped in Framingham and visited their aunt—my grandmother—on their way back to Canada. I can’t find a picture of Syd on this visit, but here is one of Jack. He is holding the hand of my father, who’s 2 1/2. Jack has the haggard look of a veteran in his fifties, but is not yet 30.

In his retirement, my father wrote several pamphlets of personal memories. One of them was about the Rows, and especially Sydney.

He wrote: “I can remember having early morning wrestling matches with him after awakening him in his bedroom. He played baseball with us. He taught me how to throw a curve ball. He joined us in our hockey games at a local pond during the winter months. He was understandably very handy around horses.”

My father, an only child, viewed Syd as an older brother. My grandmother, his aunt, viewed him as an older son. They both missed him terribly when he got married and moved out of the house. My father was 13.

Syd had two children and lived what was considered, in our family at least, an unhappy life. He got divorced from his wife, Caroline, drank heavily, and lost many jobs.

He occasionally visited my parents in Framingham when I was small. He always slept late the first morning. I have fond, if sketchy, memories of him.

My father wrote in his memoir pamphlet: “He always came with a gift. Once he brought a cribbage board and took great delight in teaching the game to our children. On his last visit he presented our two boys with a .22 caliber rifle with shells. He explained they were old enough to be responsible with a gun if they were properly taught. He then took them down into our woods where it was perfectly safe to shoot a rifle at a target. It was a big day in their lives.”

When I eventually learned about the psychological damage of war I concluded that “Uncle Syd” (as we called him) was probably one of its sufferers.

He got a shrapnel wound in his right armpit in August 1916, and suffered several skin infections, including one in his hand from a barbed-wire cut. He had tonsillitis in October 1917. On November 20, 1917–three months minus a day from when he’d won his medal–he was admitted to the hospital for “debility.” He stayed 86 days. Could that have been “battle fatigue,” “shell shock,” or some other mental wound of war?

Who knows what ghosts haunted Sydney Row from three years on the Western Front, or one summer day in the streets of Lens, France?

Recent Comments