The next day the conditions outside were even better. We paddled along St. Catherines Island. As with the islands on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, stretches of the beach were covered with the standing and toppled carcasses of trees–oaks, pines, cedars–that had once been on high ground. The water was calm except for the swell that lifted and dropped us as we paddled along.

Crossing Sapelo Sound to the north end of Blackbeard Island we saw a lot of butterflies. They were orange and black, but not monarchs or viceroys. Some had suffered too-close encounters with the water. I picked up one and was surprised to see it was still alive.

I gave a lift to two butterflies. One rode 10 miles until we got to land, where I put him on a bush. The other resumed his journey once his wings dried.

This particular day was supposed to be only 16 miles but turned out to be 20.36 miles. We arrived at Raccoon Bluff on Sapelo Island pretty spent. (The cloud of no-see-ums greeting us didn’t help). We spent the night in a campground at Hog Hammock, the only surviving community of five created by freed slaves after the Civil War.

Don had arranged for us to have a Low Country dinner prepared by the cook of the village’s one restaurant, which was normally closed that time of year. The dinner consisted of gumbo, macaroni & cheese, red rice, fried chicken, two kinds of biscuits (beaten and “cat head”), two kinds of ice tea (plain and sweet), and lemon cake. It was great. We didn’t finish anything. We took some of the leftovers for the road.

The next morning we had an audience with Cornelia Walker Bailey, the resident interpreter of Hog Hammock’s history, in her house next to the community store. She is the author of a book on the island’s folk life, called “God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man: A Saltwater Geechee Talks About Life on Sapelo Island, Georgia.”

The black residents of the coastal islands are know as the Gullah people, although on Sapelo the preferred term is Geechee. They’ve interested ethnographers for a century because they’re thought to have had a greater continuity with African folkways and language than most Southern black communities. The sentence structure of the local dialect (before it was diluted by modern exposure) was considered similar to that of some West African languages. The tradition of incorporating a prized possession into a person’s grave marker is similar to that of some West African groups. One thing Ms. Bailey said during the hour-long session suggested this thread is not yet broken.

She’d visited Sierra Leone and bought a book of local folk tales at King Jimmy’s Market in Freetown. The stories included some she’d heard as a child. “I’m going, ‘Wait a minute, Mama told me that story, and she couldn’t read or write’, ” she said. “So how come that story printed in a book in Africa is the same story that Mama told us as we were growing up? It’s amazing, almost word for word, the story hasn’t changed much at all.”

In recent decades, as younger generations moved off the island and subsistence farming and fishing became less viable, the black people of Sapelo sold most of their waterfront property to white weekenders, some of whom have built large houses on stilts. Four of the black communities, including Raccoon Bluff where we landed, no longer have any black residents at all (although the church at Raccoon Bluff still exists). The golden age of Sapelo’s black communities, Ms. Bailey said, was about 15 years after the Civil War. Black ownership of land was common and the villages were big enough to support schools, midwives, tradesmen.

“It was a happier time, it was a more fulfilled time. People were not worried about losing their land. They had just got it and acquired it. They were comfortable with that. ‘I’m a landowner. After being a slave for so many years, I own this piece of ground’. ”

We left the next morning from Duplin River at the southern end of Sapelo, crossed Doboy Sounds–it’s plural for some reason–into a creek that went through an area of marsh claimed by numerous islands (Wolf, Queens, Rockdedundy). Once again, we had to keep underway without rest in order to catch the tide. At this point we were also without the chase boat. Turney McKnight, whose kind services allowed the trip to be almost luxurious instead of painfully spartan, had headed for home.

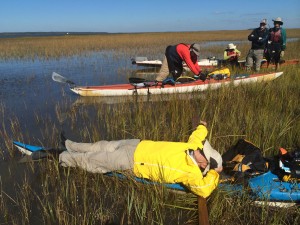

We spent the final night on an island made of dredge spoil–a ridge of coarse sand with a decade’s worth of vegetation–on the Intracoastal Waterway just across the Altamaha River. There was so little firewood that a three-person party went out in the falling light to get some from a neighboring island.

We had a dinner of pasta with sauce made from materials still left in the cooler–a “chef’s challenge.” The season had turned. It was autumn and cold.

The next day was short, cool, overcast, and windy until we turned into the protection of Wilson Creek. Our destination was Hampton River Marina on Little St. Simons Island. We got off the Sea Islands just where they became filled with millionaires and golf courses.

Some of the group caught a shuttle to the airport. The rest of us–six–once more loaded the trailer and the van, climbed in and headed north. About six hours up the road we stopped and booked three double-occupancy rooms for $49 apiece–a bargain rate that Bob Baugh negotiated with desk clerk when he learned the man had once lived in Maryland. Before the night was over we’d all gotten new rooms because of problems with the ones we’d been assigned. Still, a bargain.

Soon enough we were back in Annapolis. Ed Dryden backed the huge rig into Don’s downhill driveway with the precision of a man doing embroidery. We were almost done.

Recent Comments