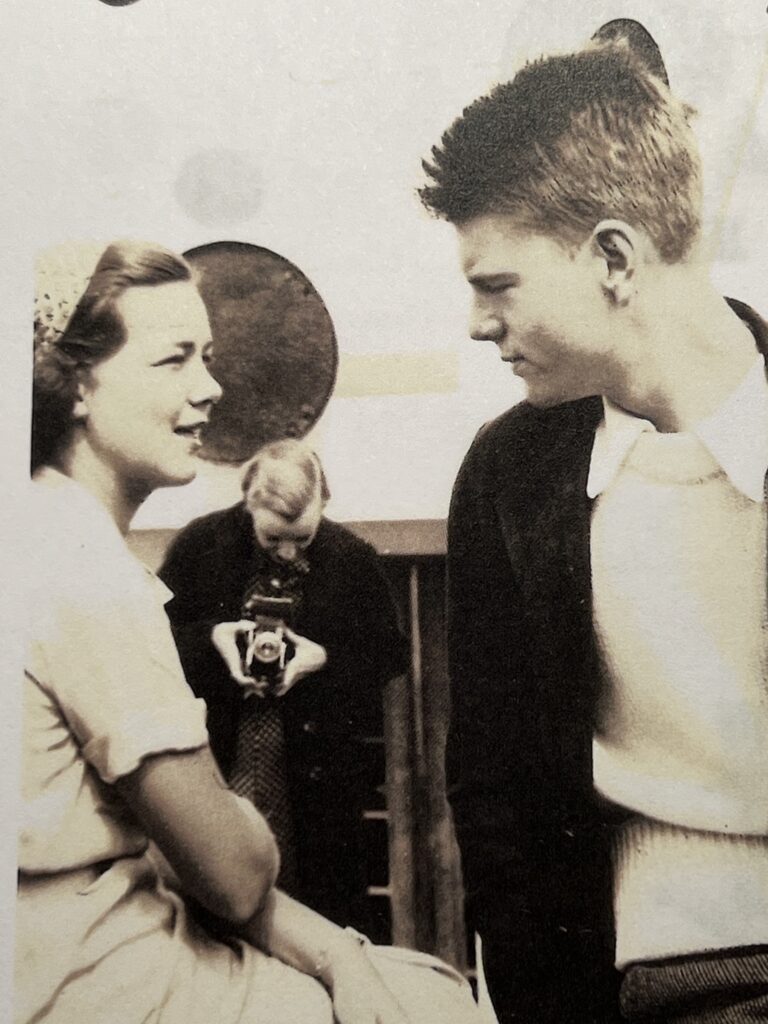

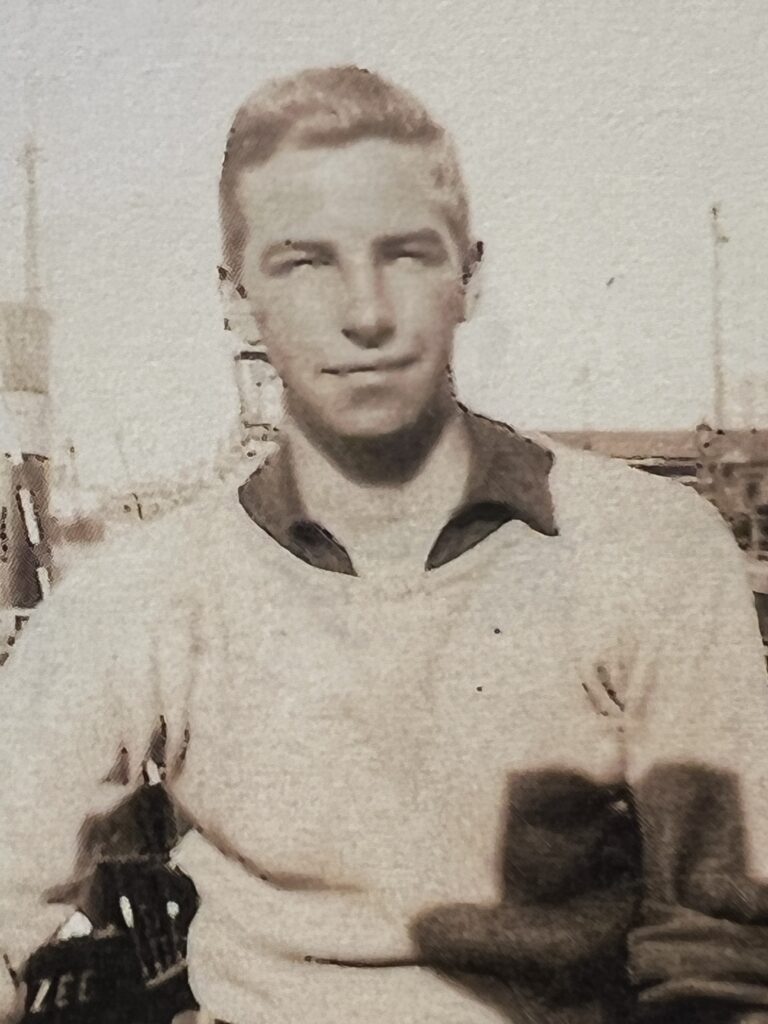

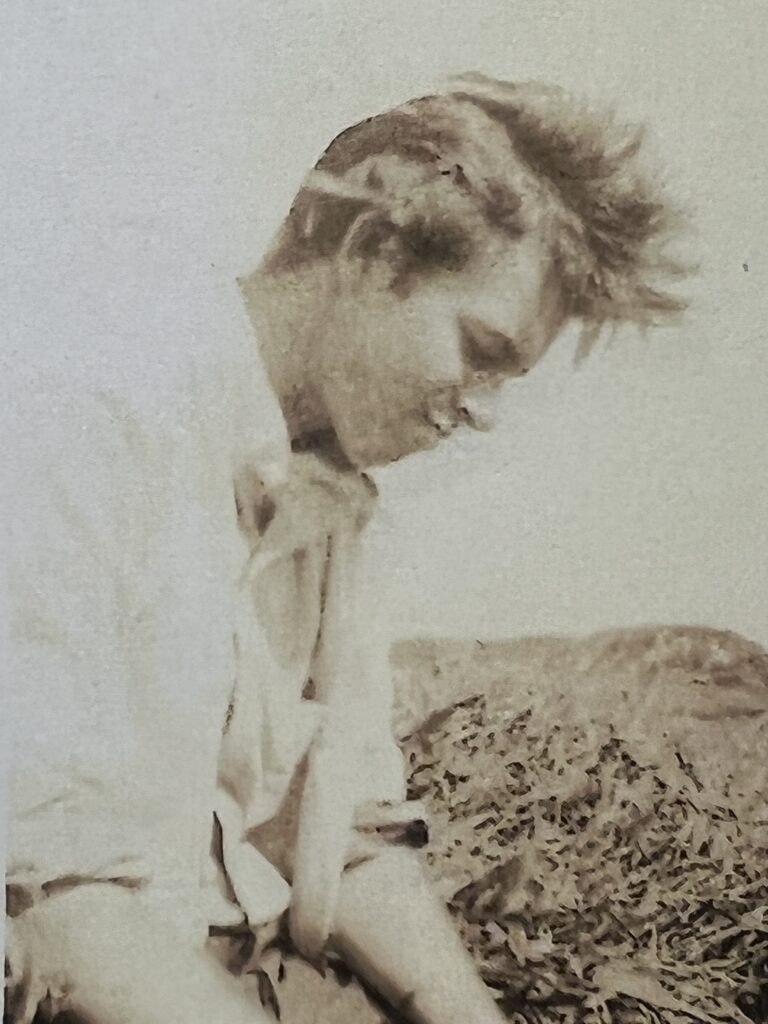

My father’s cycling companion on his bicycle trip through Scotland, England, and Wales in the summer of 1936 was John Gaylord Brackett, Jr. He was 18, my father was 19.

They’d gone to Deerfield Academy, in Western Massachusetts, together for high school, and both had just finished their freshman year at Harvard College. My father refers to John Brackett as “J.B.” in the journal he kept that summer. Whether that’s what everyone called him, or was just to save time and space in the writing, isn’t clear.

Sometime when I was a teenager, my father had told me that the person with him on that memorable adventure was later killed while training to be a pilot, someplace in the Deep South. Not surprisingly, he never said how this death had affected him. Surprisingly, I never asked, even when I was mature enough to realize it must have been a great loss, and an emotionally complicated one.

My father didn’t serve in the armed forces in World War II, although 80 percent of his classmates at Harvard College did. He’d had a kidney removed because of chronic infection, and was rejected by both the Army and the Navy when he tried to enlist. Late in the war, after graduating from Tufts Medical School on an accelerated schedule, he worked in a laboratory in Berkeley, California, doing high-altitude physiology research for the military. In the early 1950s, soon after I was born, he served stateside in the Army as a medical officer.

What was it like to spend the war out of uniform? Were there quizzical or accusatory stares? How often did he have to give a rehearsed explanation?

I have answers for none of those questions.

Of the 866 men who graduated in Harvard College’s Class of 1939, 30 died in the war, according to the 50th Reunion Report. How that number was calculated isn’t explained. Memorial Church, in Harvard Yard, lists 27 dead from the class. That was fewer than the adjacent classes recorded–31 in the Class of 1938, and 38 in the Class of 1940. (Curiously, among the names on the marble slabs is Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Class of 1904.)

There were distinguished soldiers among my father’s fallen classmates.

William Edgar Huenekens flew secret night flights into France to deliver supplies to the Resistance as part of the OSS, forerunner of the CIA. Leroy Adolph Schreiber was a P-47 Thunderbolt pilot who shot down three German fighters and damaged two others on a mission over Hanover, Germany, one night in February 1944. (He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.) Wells Lewis, the son of novelist Sinclair Lewis, fought in North Africa, Italy, and France, winning the Bronze and Silver stars (and also publishing several short stories) before being killed on October 29, 1944.

John Brackett never deployed, but was still, of course, considered a casualty of the war. He’s listed as “DNB” in official lists–Death, Non-Battle.

He’s among what’s surely the saddest and most overlooked of the war’s victims–those who died not in the good fight, but in preparing for it.

From 1939 through 1945, the United States Army Air Forces–the precursor to the United States Air Force–suffered 6,500 fatal accidents in the continental United States. In all, 15,530 people were killed, and 7,114 airplanes wrecked. There were, on average, almost 40 accidents and 10 deaths in training each day of the war. In the peak year, 1943, there were more than 5,600 fatalities.

Those astonishing statistics are from a 2013 doctoral dissertation by Marlyn R. Pierce, at Kansas State University, called “Earning Their Wings.” He dedicated it “To the 15,530.”

The study documents how the demand for pilots and flight crews grew as the U.S. military prepared for, and then entered, the war, and how the evaluation and training of recruits changed as a consequence. It’s fascinating, and full of incredible numbers. Here are a few more.

In 1939, the number of people in the Army Air Forces was a little over 22,000–12 percent of all Army personnel. In 1944, it was 2.4 million, or 31 percent. In 1939, there were 7 fatalities for every 100,000 flying hours; in 1943, there were 19 for every 100,000 hours.

The risk of dying increased as flight training progressed. The rate was 27 per 100,000 flying hours in small, “basic” aircraft, and 55 during “advanced” training, when crews were in larger, more complicated, and more recently designed planes.

This appalling mortality was far from all attributable to pilot error and inexperience.

The demand for aircraft was so great that companies such as General Motors and Packard that had never made airplanes were suddenly making thousands. Some had poor designs, with airframes and engines barely able to carry their armament. Some were inadequately tested. The number of engine fires and mid-air explosions was shocking.

John Brackett had just been commissioned a second lieutenant when he was killed on August 13, 1942 a mile west of Key Field, in Meridian, Mississippi. He’d left his third year at Harvard Law School and enlisted, taking flight training in Florida, and at two other bases in Mississippi.

Brackett’s father was a “special justice of the Boston Municipal Court,” according to a four-paragraph story in the Boston Globe. His paternal grandfather was John Quincy Adams Brackett, who’d been governor of Massachusetts in 1890, when gubernatorial terms were one year.

Brackett was flying a Douglas DB-7B “Havoc” light bomber. He was in the part of training called “night transition”–learning how to take off and land in the dark. In combat conditions the plane had a crew of three–pilot, gunner, and bombardier–but as this was just flying practice, only the pilot was on board.

An online data base of thousands of aviation accidents lists the cause of this one as “take off accident due to engine failure.” That same night, flying from the same airfield, the same type of plane crashed, killing the 23-year-old pilot, 2nd Lt. Walter J. Miers, of Crowley, Louisiana. The cause of that crash was “engine failure and fire.”

An Associated Press report said: “Witnesses said Brackett’s plane exploded immediately after clearing the landing field and the other accident occurred a minute after Miers took off.”

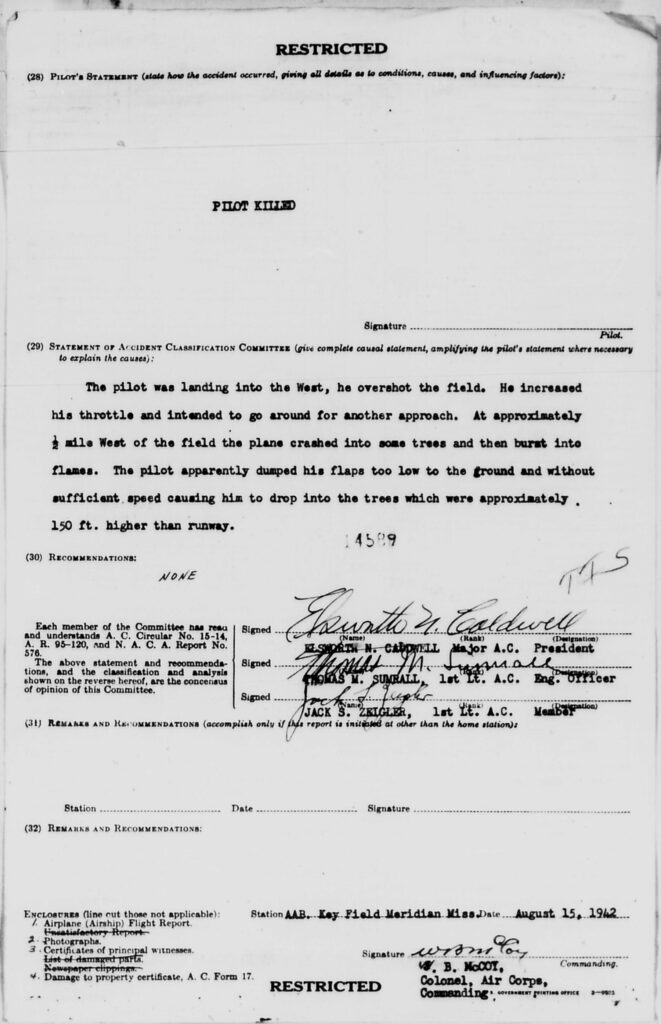

The official report of the crash, which I obtained from a website called Aviation Archaeological Investigation & Reports, tells a different story.

The cause of the crash was judged “100 percent Pilot Error,” and in that category it was judged to be 100 percent due to “Poor technique.” John Brackett had overshot the airfield in an attempt to land and was going around to make another approach when he lost air speed and crashed into a patch of woods off the base.

One part of the report said he “dumped his flaps too low to the ground.” I’m not sure what that means, but it was clearly a mistake. He’d had 235 hours of flying since enlistment, and 24 hours in the model in which he died.

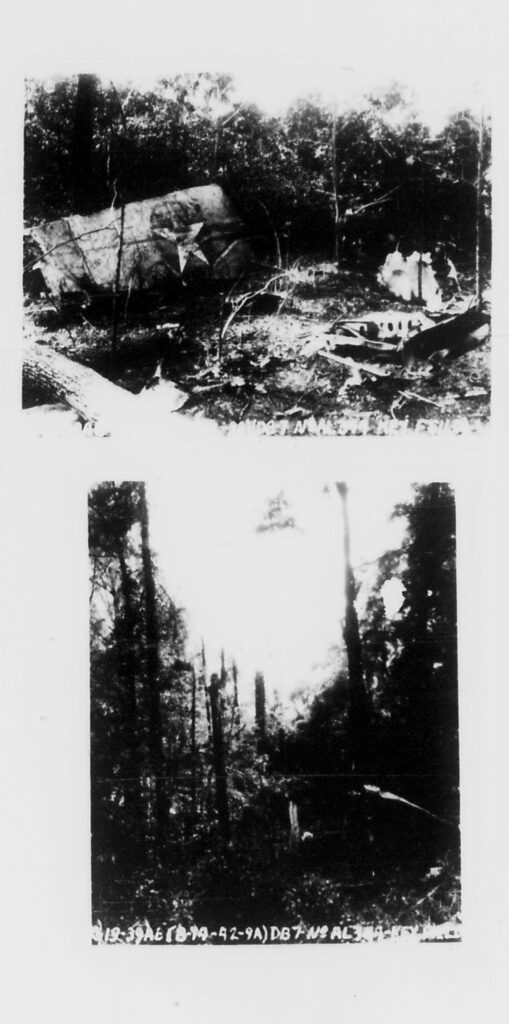

Here’s a picture of the crash site, and some of the wreckage. The destruction is total. One hopes death came quickly.

John Brackett was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, the resting place of Boston bluebloods, and many famous people (Nathaniel Bowditch, Winslow Homer, Mary Baker Eddy, Fannie Farmer, Bernard Malamud, Felix Frankfurter). My father was one of the five honorary pallbearers. After that, Bruce Brown kept his grief to himself. Or at least from his children, which I realize is not the same.

As it happens, the land I’ll be walking across in the next two weeks with my friend Mark Beckwith is sacred ground.

Scotland was the training ground of thousands of airmen in World War II. About 5,000 airplanes crashed there during the war, mostly in the Highlands, which are open and treeless. Wreckage of about 300 remain visible today. I passed one site in 2015, on my second crossing. All that remains of the Audax Harrier is part of the airframe and scattered pieces of metal.

The two people in the plane survived the crash in 1939, but not the war. One was killed in 1940 in the Battle of Britain. The other disappeared in 1942 in a bombing run to Flensburg, Germany, no trace found.

The deaths of young men learning to fly is part of the collective memory of northern Scotland, and in the individual memories of some of the people still alive from that time.

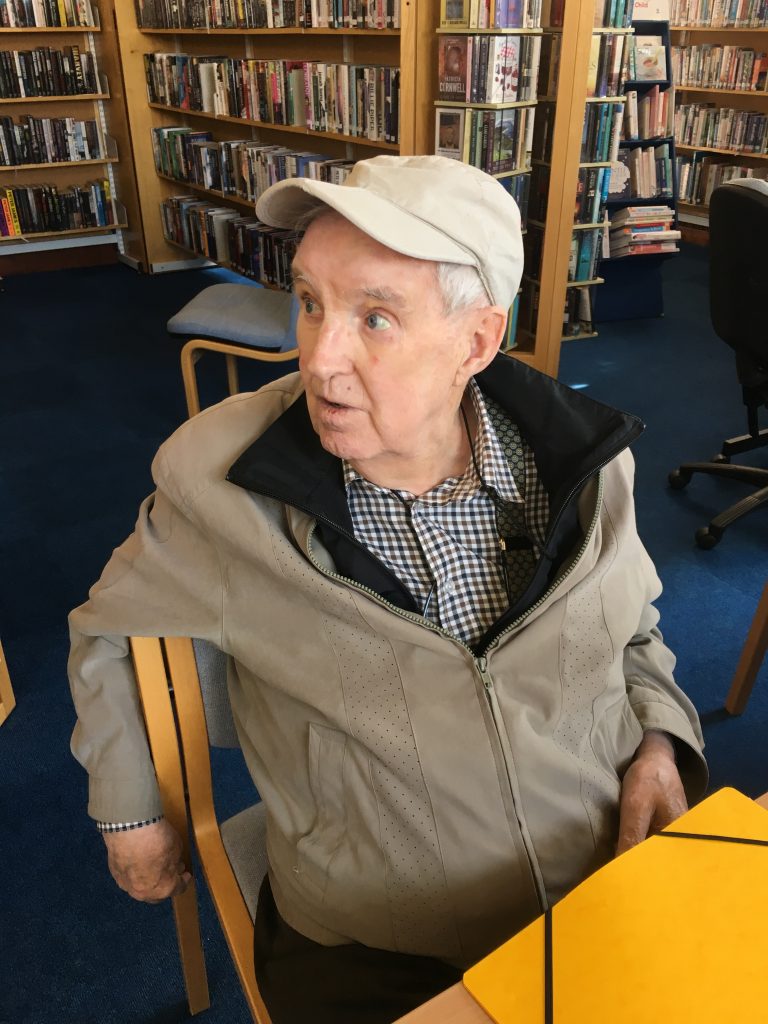

In 2016, when I walked along the Moray Coast I met and interviewed a man named Donnie Stewart. He grew up in Lossiemouth, a fishing town where an airbase was built in 1938. He was a preteen during most of the war. To him and his gang of friends, watching the fortification of the coast (and helping in small ways) was a great adventure. So was watching the airplanes come and go–and occasionally crash.

“We regarded this as entertainment,” he said ruefully.

A long time later a stranger came to Lossiemouth and inquired whether anyone recalled a crash that killed three Australians, including the man’s uncle, Ed O’Dwyer. Donnie did.

All on board died, as did a would-be rescuer who tried to swim out to a rocky island where the fusilage landed. Donnie described in detail what he’d seen. That gave the man some solace, and it assuaged somewhat Donnie’s decades-old guilt.

He knew the numbers. “Three-hundred eighty-four people died learning to fly out of the Lossie aerodrome,” he told me.

The psychological stress of being a novice pilot in wartime was clear when I interviewed a man named LaVerne Schaaf in a small town in Iowa in 2007 for another project. He’d been on the ground crew at an airbase in Alaska for two and a half years. It was hard to know which was more dangerous in the Aleutian Islands, Japanese fighters or the weather.

“We lost over a hundred men out of our outfit. They’re laying there in the bottom of the Bering Sea, up there. I don’t know how many pilots we lost,” he said, the sadness and disbelief still evident six decades later.

“The last guy, I felt so sorry for him. I put him in a plane–that was when we were on Amchitka–and helped strap him in. He was shaking so bad. He was a warrant officer. It was new to him, first time in combat.

“I told him: ‘You’re shaking so bad, you don’t have to go. You can turn yourself back in.’

“He said: ‘Well, they’ll court-martial me.’

” ‘I know. But you’ll be alive.’

” ‘Yeah, but my Dad and Mother are proud of me. I’m a pilot in the air force. I’m going through with it.’

“I said: ‘Well, all right.’

“What he did, he never gained flying speed when he took off. He got a good half-mile out there and he lost flying speed. He went down, to the bottom of the ocean. There’s where he’s laying today.”

How many people are alive today who knew John Brackett? There can’t be many.

His parents are gone, of course. He had two sisters, so I suppose there could be a niece or nephew still alive who may have met him. My father, who could have told me about what he and John did in Scotland–beyond what’s in the journal–is gone, as is everyone else from the Harvard Class of 1939.

Soon, John Brackett will recede into the deep silence of history, where we exist only as names, stories told no better than second-hand, and (if we’re lucky or had been so inclined) maybe an object or piece of writing or music that’s survived.

It reminds me of a poem by Emily Dickinson:

I died for beauty, but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

“For beauty,” I replied.

“And I for truth–the two are one;

We brethren are,” he said..

And so as kinsmen, met a night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

The moss has almost covered up John Brackett’s name, as it will ours in due time. As I walk across Scotland, maybe for the last time, I will keep him–little as I know of him–in mind.

Very fine reporting, moving, artfully restrained writing. To John Brackett and Bruce R. Brown; and a thank you to David Mosser Brown.

Who knew Dad was such a cyclist. I wonder how many gears the bikes had?? And it was true mountain biking at times! Thanks for documenting this. It’s wonderful.

Wow. Powerful and sobering.

My father, who was 32 when Pearl Harbor was bombed, also tried to enlist and was turned down, because of a knee injury and because his job teaching engineering was considered more valuable. He spent the war turning out 90-day wonders at Columbia. He was exhausted by the work, haunted by the knowledge that many of his students would go off to the South Pacific to die (where his brother was serving on a PT Boat) and very conscious of not being in uniform in wartime New York.