I’m back in Scotland to once more to spend two weeks walking from the west coast to the east coast of the country.

Why, you might ask?

I’ll answer only because I’ve asked myself the same thing.

There isn’t an overarching reason. But among the top few is that it’s a physical accomplishment still possible (at least I think so) in my early 70s. That can’t be said for running a marathon or swimming across Chesapeake Bay or climbing Mt. Ranier (which I never did)—all of which I might still be capable of doing, but for which I lack the willpower. I still have the willpower to walk across Scotland.

The sense of accomplishment lasts a few weeks—a bargain.

The Great Outdoors Challenge was my “discovery,” with a major assist from Roger Hoyle, and lesser assists from Kathy Lally and Will Englund, who introduced me to Roger in Moscow in the fall of 2013. So, I feel proprietary about it.

The people who do the event—“Challengers”—are energetic, talkative, and modest people with interesting stories to tell. They speak English and tend to be old. They inspire and are pleasure to tarry with.

The Challenge is the only perfectly run event I’ve ever been around. The coordinators who run it (and the other volunteers they impress to help them, and us) are models of selfless and thoughtful devotion to a complicated enterprise. No corner is cut, no detail is overlooked. Watching it unfurl each year is both education and entertainment. It’s the way things should work.

Scotland is beautiful, and Scottish people friendly.

Going away for most of May also prods me to finish things. After a career of nail-biting deadlines all I do now is bite my nails and break self-imposed deadlines.

However, in the two months leading up to this event I hosted two of my oldest friends for a five-day visit after talking about it for 20 years; did a three-day volunteer program in a prison; made arrangements for two home-improvement projects to be done while I’m away; pitched a complicated story to a reporter; drained the hot tub; finished planting the vegetable garden; and (hours before I left) mulched two saplings.

I should go away more often.

That said, whether I go away to do this again next year is uncertain, which I know I’ve said before. It may be time to walk across Ireland, or around Wales.

However, I definitely wanted to come back one more time so I could visit a monument to a long-ago ancestor, John Brown (who interestingly is not from the Brown side of the family). He was shot in cold blood by the religion police, which in 1685 were also called the army.

Just this afternoon, as I waited at a bus stop in Auchinleck to go the two miles to Cumnock, where I am now, I chatted with a woman with three face nails and an accent that was hard to understand through. She asked why I was here. I told her “to see the John Brown monument at Priesthill.” “I’ve been there,” she said. “Very pretty.”

That’ll be the subject of the next two blog posts. Grab a drink and buckle your seatbelt.

Which gets me to my route for this year. (Despite what I’ve said, the Challenge is all about the route. But that’s a blog post in itself, which you’ll be happy to know I won’t write.)

This year’s route is not inspired, and not even very new. I’ll be traversing some unfamiliar territory, but also a fair amount that’s old. The route is also soft—eight nights of camping and five nights of staying indoors. But it has something to recommend it: I’m sure I’ll meet people.

Two of the five crossings I’ve done were at the edges of the permissible territory. In one I met no Challengers in 13 days; in the other only a few. This time, I want company.

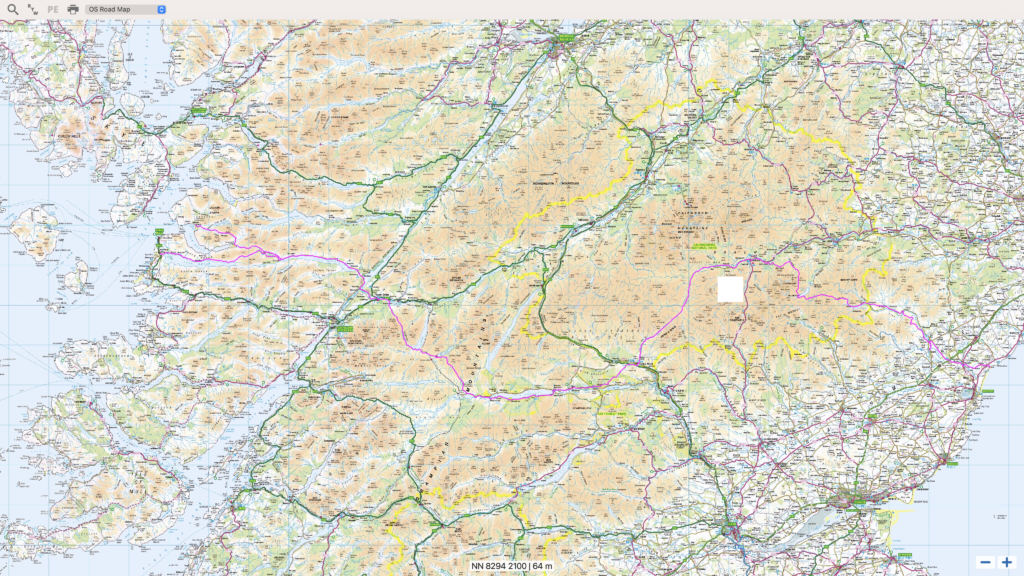

Here is my route for this year.

It’s the barely perceptible pink line across the middle of the map. The discerning eye will note there are two start points, and two initial routes, on the left (western) end of the walk. The more southern starts at Morar, which leads to an unusually difficult first two days. The more northern is starts at Inverie after a ferry ride from Mallaig. It is easier and safer two days. I haven’t decided which one to take.

My pack (“rucksack” over here) weighed in at 41 pounds when I left Baltimore. There will be repacking and mailing of items, but I’ll be lucky if it’s less than 40 pounds when I take off.

It contains (among other things) 2 pounds, 11 ounces of wind shirt, rain pants, rain jacket, puffy jacket, mittens, hat, and scarf; a 4-pound, 14-ounce bombproof tent; 3 pounds, 5.1 ounces of sleeping bag and pillow; and 5 pounds, 14 ounces of electronics. The clothes, toiletries and first-aid materials, and other things I haven’t weighed.

I also have 7.7 pounds of gorp, which will be 13 days of lunches. (With some to share; it’s famous gorp.) I’m going to divide the gorp and mail most of it, along with varying numbers of freeze-dried meals, to pick-up spots where I’ll stop along the way.

That repacking will be done at the home of my friends Deborah and Paul Richard in Argyll, on the west coast. The British-made freeze-dried meals I ordered have already been delivered there. The Richards have, once more, agreed to be my final-days’ hosts and logisticians, as they have for four of my five Challenges. They’re also terrific company and I’m lucky to have them as friends.

I can’t resist adding some random facts I learned a few months ago.

In the buildup to the Normandy invasion, most American troops left from Glasgow and nearby Greenock to go to the southern coast of England, whence they left on D-Day. In “The Guns at Last Light,” the third volume of Rick Atkinson’s magisterial trilogy about the U.S. Army in Europe in World War II, he reported that 100,000 American soldiers arrived in Scotland in April 1944 alone.

The combat load of the average rifleman shipping out of Scotland was 68.4 pounds, Atkinson wrote. (That included a life belt.) The recommended weight of kit for assault troops going ashore in France was 43 pounds.

I’m carrying less than them. And that’s the only comparison I’ll make.

What a wonderful beginning — and a great pleasure to read. Thanks for bringing us along!

There you go again. And with what impulse and brilliance!