Madeleine Braithwaite-Exley wanted to take a picture of me after I took a picture of her before I set off. Here it is.

I didn’t want to head back to the road to get on my route, both because it would add distance and because road-walking is harder on the feet (and often distracting and annoying). So I headed cross country from the dead-end of the farm track that had led to her house.

This is the way it’s been on a lot of this crossing—walking on ground that has no trails according to the Ordnance Survey map. In truth, there is a whole system of capillary paths—not the veins and arteries on the map—one can find and follow to stay off the roads.

What you have to be willing to do is open and close gates, climb over fences, and cross streams of unpredictable depth. Sometimes the paths are animal trails of barely perceptible contour; sometimes they are trodden into a strip of bare dirt capable of holding their identity even in the lushness of spring.

It’s fun to try to find these, or intuit where they might be. But you have to be prepared for an end of the road and an invitation to bushwhacking.

I went through a patch of woods behind the B&B on an old ATV track.

Here are a few other paths from the day. The third shows a farm track with some boot prints. I suspect they might be from a Challenger. I’ve still not seen one.

I passed something called the Lundie Craigs. They’re unlike anything I’ve seen over here. Most cliffs are part of the hill or mountain; this was like a mesa.

I crossed a pasture full of cattle—cows not bulls, I surmised—staying high on the slope and away from them. I went through a gate into a sheep pasture. I found a spot free of sheep droppings next to Long Loch. I’d passed a house, but saw no one.

When I arrived I seemed to disturb the order of things on the water. A swan chased a pair of geese mercilessly for about 15 minutes. I set up the tent just before it started to rain. The rain didn’t last long. You can hear it in this quick video tour of the accommodations.

After dinner, things had calmed down and the geese were nowhere to be seen.

The next morning I walked to the end of the loch and confronted the Challenger’s nemesis—an electric fence. I considered doing a scissor-kick high jump (which I was once good at in summer camp), but decided against it. The last thing I needed was a twisted ankle or knee. So I put on my mittens and quickly climbed the wire next to a wooden post, where I could put a hand. I got over without a shock.

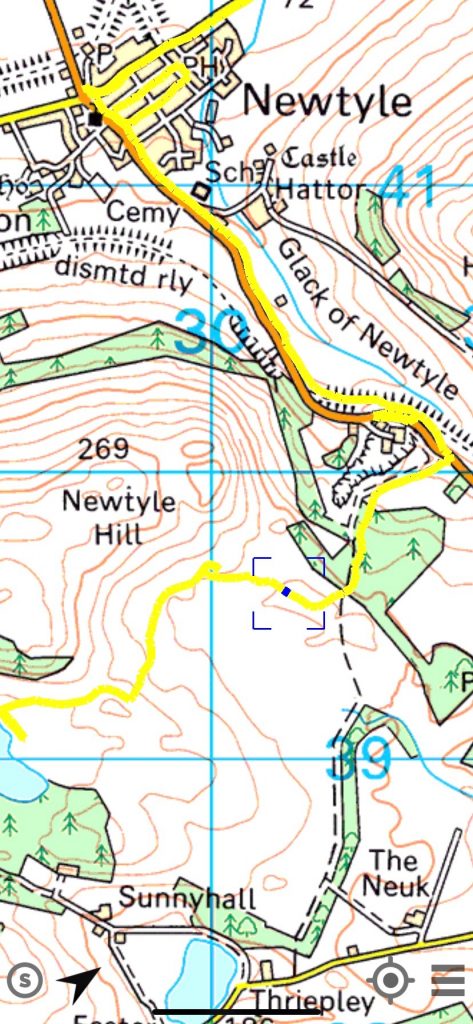

Just to give you a sense of the mix of walking, here is my tracklog, in yellow, for the first few hours of this day.

The lower left corner, near the water, is where I went over the electric fence. I then cut across open ground, encountered several other fences that took some effort to get over (but weren’t electrified) before getting out onto boggy, hummocky ground on one side of Newtyle Hill.

I followed what looked like a trail but, as you can see from the buttonhook detour in the middle of the image, turned out to be a dead end. This is what looked like looked a trail through the gorse.

You can’t bushwhack through gorse. It’s like cactus, only more luxuriant. It’ll ruin raingear in about 10 seconds and then start tearing flesh.

So I tried going in another direction, not the heading I wanted, and found the dotted-line trail on the map. This is looking back to the gate I just came through off aforementioned Newtyle Hill.

This is just to make the point that there’s lots of trial error in this enterprise. Unsuccessful choices add time and effort.

Then there was quite a bit of road-walking.

You pass steadings like this often. Isolated and neighborless, low, solid, heat-retaining, they represent to me the historically hard life of rural Scotland. And of course, they’re palatial compared to what people lived in 200 years ago.

Everywhere are stone walls built to a stereotyped design: two courses of stacked flat stones with rubble in between, and a rounded cap along the top. The cap is first to go; nevertheless, in many places the walls are intact.

The difference between these walls and the ones I grew up with in New England is the difference between a system of feudalism and crofting and a system of fee-simple ownership and yeoman farming. In other words: if you own, you don’t have to be so compulsive.

The wind sent the oats—higher than the other crops—undulating. You can see it in the middle distance if you enlarge the picture.

I was supposed to spend the night at a B&B in the village of Letham. I was hours behind schedule and called the woman who runs it. I told her I might not make her place until 9 p.m. She suggested I stop short and try to find a place in Glamis, a village I was only a mile from.

In a few minutes she called me back and reported that Glamis (pronounced Glalms) had a hotel, and advised I go there.

There’s nothing like a foster mother when you need one.

I spent the night here.

Nice photo and just as well to avoid a shock!

It may have been difficult but at least you got to see the Glack of Newtyle. Not everyone can say that.

Hello David I throughly enjoyed following the blog about the Challenge walk.

Your writing is so smooth and easy to follow. The content and day by day kept me interested. Now for some sailing challenges

Ken