The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged-the same house, the same people- and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence. He caught a glimpse of his mother waving from an upstairs window, and that unfamiliar gesture disturbed him, as if it were some mysterious farewell.

Vladimir Nabokov

“Speak, Memory” (1951)

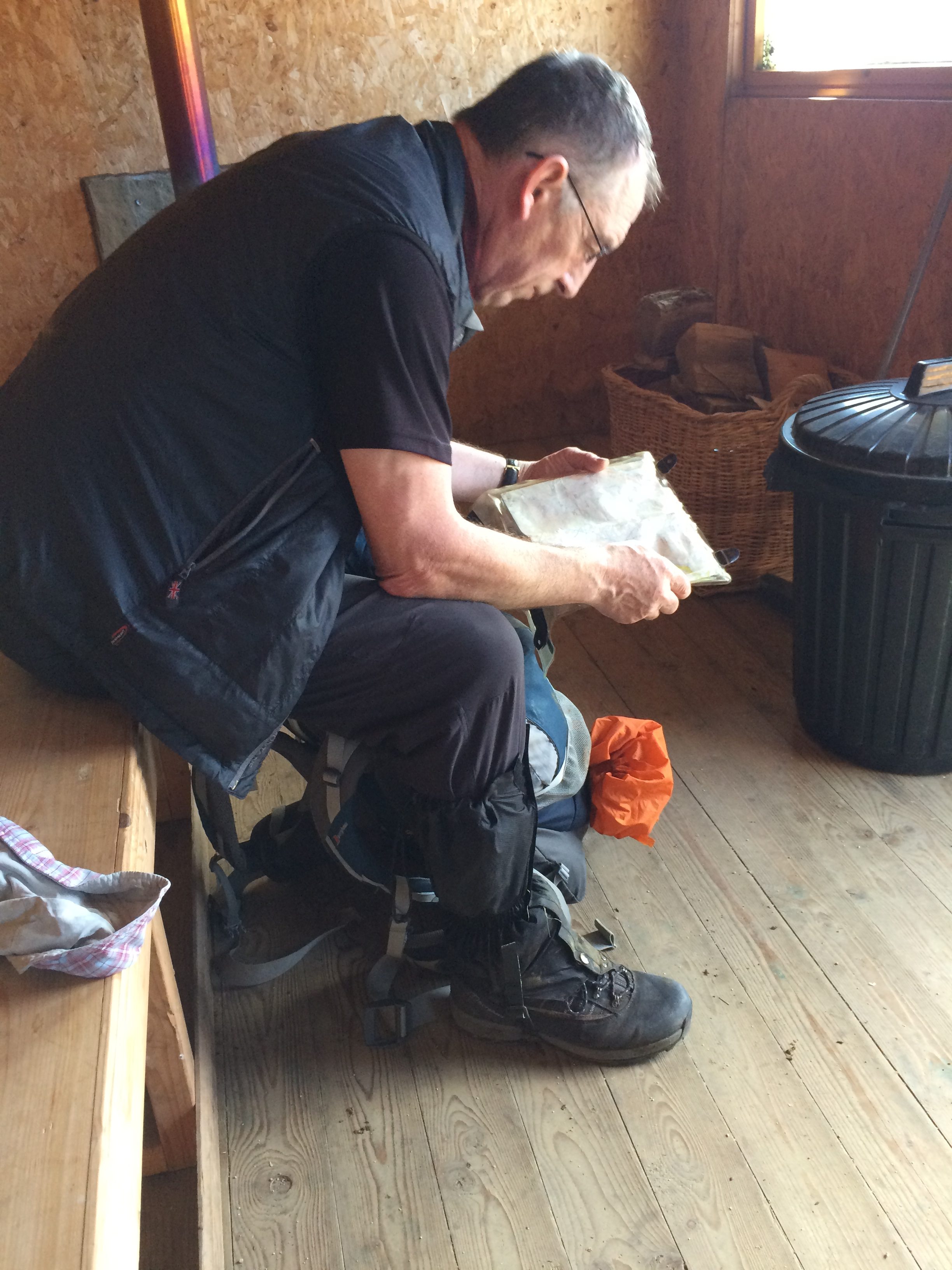

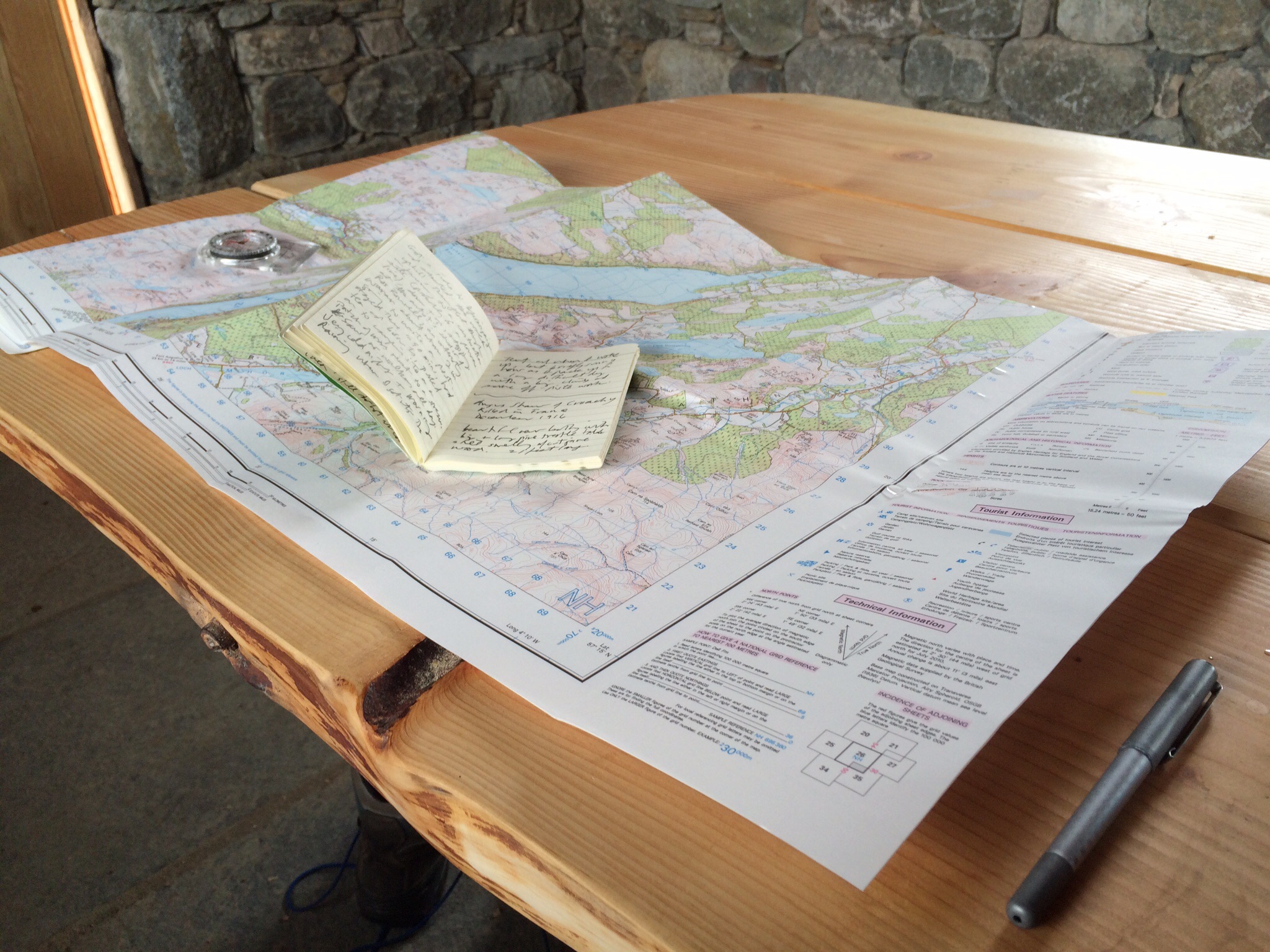

This post is not about my walk across Scotland. But walking across Scotland brought me to it.

It’s about a Scotsman who was once in love with my mother and wanted to marry her when she was barely out of her teens. His name was John Patrick Oliphant Russell. He was called “Pat.”

My mother only mentioned him to me once or twice. My father late in life described him as “a Scottish man who wanted to marry your mother and was killed in the war.” I’ve been able to find out a bit about him, and I visited his childhood home, in Fife on the east coast, after finishing The Great Outdoors Challenge.

My interest in Pat Russell and my mother arises not from the mystery of what was before but from the mystery of what might have been, and the tragedy of what actually happened. It’s not exactly what Nabokov was talking about, but not entirely unrelated. In any case, the quote is too good to pass up.

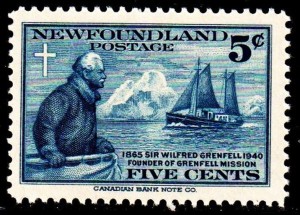

In 1938 my mother, born Sally Jane Mosser, went to Newfoundland to work for the Grenfell Mission. She may have gone another time, too–the year before or the year after–but I don’t know for sure. That I don’t is an inexcusable oversight for a reporter. But it’s too late now.

Wilfred Grenfell (1865-1940) was an English physician and missionary. He is described in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography as “one of the last of the spiritual adventurers, the manly Christians who carried the code of service into the remote places of the earth at a time when such a philosophy of life was still possible.” His father was an Anglican minister and schoolmaster who died by suicide. Wilfred was called to missionary work after attending a tent meeting in 1885 while in medical school in London. The preacher was the American evangelist, Dwight L. Moody.

Grenfell had a complicated and adventurous life, full of failure and success. Originally a doctor-and-preacher on a hospital ship serving North Sea fishermen, he became aware of the poverty and ill health of the residents of Newfoundland and Labrador, both white and native. Those two places were part of “British North America,” the remnants of the British Empire’s New World holdings. They didn’t become part of Canada until 1949.

Grenfell launched a program to improve the lives of the coastal people, eventually building two hospitals, clinics, a saw mill, a fox farm, a cooperative store, an orphanage and other improvements. To publicize his efforts and raise money, he wrote books and articles about life in the subarctic. One of his narratives, “Adrift on an Ice-Pan,” recounted how he fell through the ice with his dog team south of St. Anthony, Newfoundland, on Easter Sunday in 1908. They all scrambled onto a floe and were carried to sea. Before he was rescued, Grenfell sacrificed three of his dogs to warm himself with their hides, and fashioned a flag pole from their leg bones to wave for help.

Grenfell believed the people of Newfoundland and Labrador needed a lot more than medical care. They needed, for starters, more income. In 1905, he invited Jessie Luther, a social worker and artist who’d worked at Hull House in Chicago, to organize women in St. Anthony to make hooked rugs for sale. “Grenfell mats,” which depict scenes of coastal life, are today valuable pieces of folk craft.

One of the places they were sold was in a store in St. Anthony visited by coastal steamers, some of which were carrying tourists by the 1930s. My mother helped run the store.

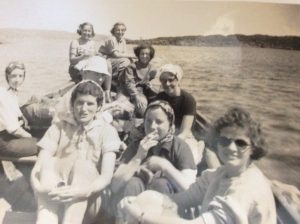

There were a lot of young people from far away working at St. Anthony. From my mother’s photo album, there seem to have been roughly equal numbers of young women and young men, although you can’t tell that from this picture. (My mother is in the bow on the left).

One of the young men was Pat Russell.

Pat was the second child of David Russell and his wife, Alison Blyth. David Russell was president of Tullis Russell, a paper manufacturer founded in 1809. They were very wealthy.

Tullis Russell had a history of enlightened management, providing pensions and health care to employees before that was common practice. The Russell family considered the workforce of a thousand people to be an extended family. That tradition led, in 1994, to the sale of a controlling interest of the company to its employees.

For years, Tullis Russell was a model for employee ownership of industrial companies. David Erdal, its former president (and David Russell’s grandson) who midwifed the sale, wrote and lectured advocating that form of ownership. Unfortunately, global economic forces caused reversals in recent years, and the company’s paper-making business declared bankruptcy on April 27, about a week before I arrived in Scotland. Tullis Russell survives, however, as a maker of coatings for paper and other surfaces, with sites in England, South Korea, and China.

When I contacted David Erdal last winter and inquired whether anyone who knew Pat Russell was still alive, he answered: “Alas, Pat’s generation are all dead.” But he kindly told me some of the things he’d heard from his mother, Sheila, who was Pat’s younger sister. Erdal’s sister, Alison Johnston, also provided memories of what she’d heard.

Erdal said there was an odd dynamic in the family. His mother and her brother, also named David Russell, were the older children of their respective sexes and treated as favorites. The other two children, Pat and Anne, “were less fortunate.” Erdal’s sister recalled hearing from their mother that Pat came home on a visit one summer and was not warmly welcomed. He said to his sister: “I don’t know why I come.”

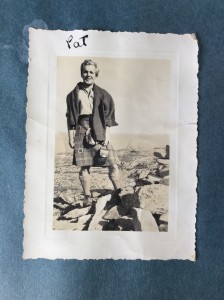

Pat was an outdoorsman, an athlete, a bit of a wild man. According to a family story, he once dived naked into a Highland stream and caught a salmon with his hands. (That would be a feat on two counts). He wore kilts, and joined the Army reserve force before the war. Scotland has a long history of producing warriors.

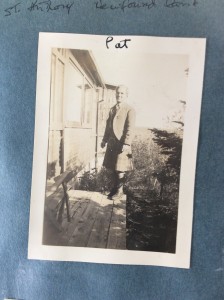

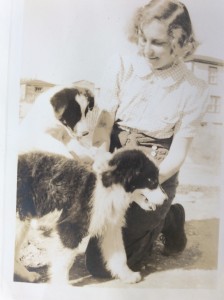

This is a picture of my mother in Newfoundland with Newfoundland puppies, probably in the summer of 1938, when she was 20. She graduated from high school in 1936 and then went to the Katharine Gibbs School to become a secretary. What year, I’m sorry to say, I don’t know.

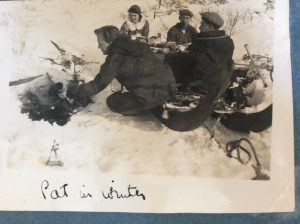

The details of their relationship are unknown. Her photo album has views of St. Anthony and pictures of activities that summer, some of which include Pat Russell. There are also pictures of Pat doing things in other seasons. Here he’s making a fire in the snow.

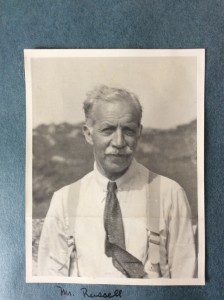

In the album there’s also a picture of Pat’s father, who was knighted for “service to industry,” and known thereafter as “Sir David.” Erdal thinks the photograph was taken on Iona, the Hebridean Island where the Russell family had a summer house. Sir David was a rare bird. He was a Presbyterian mystic. He paid for much of the restoration of a ruined monastary on Iona, where the Irish monk St. Columba brought Christianity to Scotland.

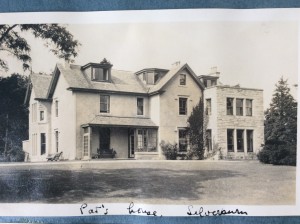

There’s a picture of Pat’s home, called “Silverburn,” in the town of Markinch in Fife.

I assume Pat sent these Scottish photographs to my mother. If she had gone to Scotland to visit him and taken them herself, I think I would have known.

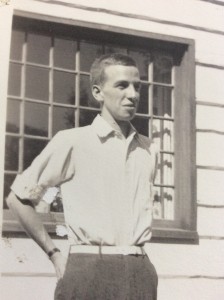

In a different album, one not dedicated to her time with the Grenfell Mission, are other pictures of Pat Russell.

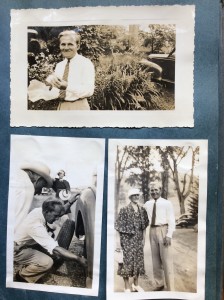

They show him on a visit to Kennebunk Beach, Maine, where my mother’s paternal grandparents had a summer cottage whose inhabitants included a maiden aunt and lots of sojourning children and grandchildren. There are pictures of Pat eating a sandwich, changing a tire, and posing with my mother’s grandmother. He’s handsome, handy, and presentable–a perfect candidate for son-in-law.

The one thing my mother mentioned about this visit was that it lasted a long time. After a few days, she was at a loss for what to do to entertain Pat.

I tracked down a mention of this visit in the diary of Kenneth Roberts, which is in the Rauner Library at Dartmouth College. Roberts was one of my mother’s uncles (married to her father’s sister, Anna). He was a famous historical novelist who once appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Some of his books are still in print.

He was also an angry and insecure man who never said anything nice about someone if he could find something unpleasant to say. He had no children. My mother was his favorite niece, and he invited her to become his live-in secretary in Maine. She wisely declined. Another niece, Marjorie Mosser, accepted the invitation, married late and had no children.

On July 5, 1939, Roberts wrote: “After dinner Sally came over, bringing a young Scotsman named Pat, who’s here for a month to woo her, as the saying goes. He was a quiet, colorless, chunky young man, who talked as though he had a mouthful of blueberry pie.”

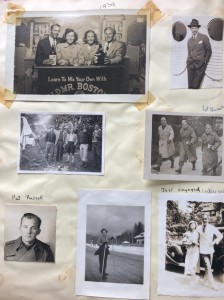

In my mother’s picture album there’s also a page with the date “1939” at the top that includes three pictures of Pat Russell.

The one in the upper left, we can be certain, was not taken at the Grenfell Mission. Four people are seated at a bar in front of a painted backdrop of a saloon. They have their hands on large bottles of liquor, and the front of the bar has the slogan “Learn to Mix Your Own with Old Mr. Boston,” a low-price line of liquor. My mother is the woman on the right. On the left is her friend, school classmate, and fellow Grenfell alumna, Debbie Bankart. They don’t look entirely comfortable.

Farther down the page are two pictures of Pat in uniform, one a candid shot of him striding along with two other soldiers.

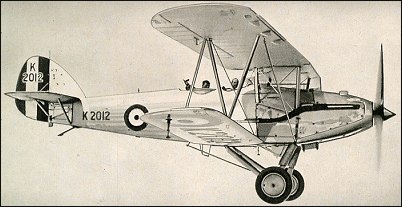

Pat Russell was in the 334 Battery of the 101 Light Anti-aircraft/Anti-tank Regiment of the Royal Artillery. Shortly before his death, he was transferred to the 1st Battalion London Scottish Regiment.

Pat’s brother David was in the 7th Battalion of the Black Watch. He fought at El Alamein in Egypt, where he was wounded and won the Military Cross for “conspicuous gallantry.” He was also wounded in Sicily and at La Havre, before being “invalided out” of the service. He is lucky to have survived.

David Erdal wrote to me: “David had had a leg blown off by a mortar shell landing at his feet. He had been triaged into the ‘hopeless’ cases. But the surgeon had asked who he was, and because they were old friends, had taken him out of the ‘virtually dead’ group and saved his life.”

He was known as “Major Russell” for the rest of his life.

Sometime early in the war my mother met my father, who was in medical school at Tufts, in Boston. My mother was a secretary to an assistant dean at the school.

My father had graduated from Harvard College in 1939. When the United States entered the war he tried to enlist in both the Navy and the Army, but was turned down because he had only one kidney. (The other had been removed the year after he graduated because of chronic infection following a sports injury.) He finished medical school and an internship on accelerated war-time schedules, and in 1945 did aviation medicine research at the Donner Laboratory in Berkeley. He served stateside in the U.S. Army Medical Corps from 1953 to 1955.

I once asked my mother how many men had proposed to her. (Can you imagine such a question!) She wouldn’t answer. But I’m pretty sure Pat Russell did.

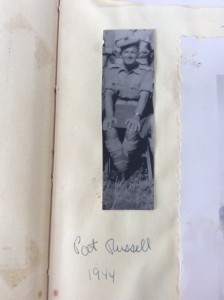

The last picture of him in her photo album appears to have been cut from a group shot. He’s wearing a kilt and a tam. It’s dated 1944. My mother and father were married on March 13, 1943.

Pat Russell died on September 7, 1944, on the Adriatic Coast of Northern Italy. He was part of the fierce fighting to break the Gothic Line, which was the German army’s last major line of defense as it retreated northward. The line had 2,376 machine-gun nests, 479 anti-tank, mortar and assault gun positions, 130,000 yards of barbed wire and many miles of anti-tank ditches, according to Wikipedia. He was killed not far from the town of Morciano (marked in red).

I hired a researcher through the Forces War Records website to search for information about the circumstances of Pat’s death. He didn’t find much. All the unit diary had was this entry for 6.30 a.m. on what appears to be September 7, although the date is missing:

I hired a researcher through the Forces War Records website to search for information about the circumstances of Pat’s death. He didn’t find much. All the unit diary had was this entry for 6.30 a.m. on what appears to be September 7, although the date is missing:

“Enemy counter attack commenced and DFs called for. Some prisoners taken and some equipment. Attack beaten off, but some casualties received. Amn running short. Coys [companies] and Tac HQ shelled and mortared for rest of day. D Coy received heavy casualties. B Coy withdrew from MENGHINO. Capt RUSSELL wounded and later died.” The entry on September 9 lists the battalion’s casualties over four days as “approximately” 11 officers and 220 enlisted men, with 3 German officers and 50 German enlisted men captured.

David Erdal, however, was able to provide some details.

“In September 1944 Pat’s parents received on a single day two separate telegrams, some hours apart. One informed them that David had been ‘gravely wounded’; the other that Pat had been killed. I understand that his unit had been pinned down by a German sniper in the mountains in Italy, and since he was acknowledged as a crack shot he had volunteered to go forward to try to kill the sniper. However, the sniper wounded him in the shoulder, a particularly painful wound. Nobody could rescue him, so over quite a long period of time he bled to death.”

It must have been an agonizing death. And one that at some point he knew was inevitable.

David’s sister, Alison, added another detail. The family’s nanny and retainer, a woman named Annie, took the phone call that day from Miss Spence, Sir David Russell’s secretary at the paper mill. The secretary said a telegram had arrived announcing Pat’s death. “Annie burst into tears. Granny went to comfort her, and Annie had to tell her that it was not a relative of Annie’s that had been killed, but her son.”

Pat’s parents grieved for him for the rest of their lives.

They kept his bedroom at Silverburn as it had been when he left for war. Sir David took one quarter of the shares of the Tullis Russell company–the fraction Pat would have inherited–and put it into a charitable trust. It still supports local charities and educational institutions, “in memory of Captain Patrick Russell.”

How did my mother learn of Pat’s death? Did his parents write, or possibly call? How did she get a picture of him from 1944, a year after her marriage? Still almost a newlywed, how did she mourn?

She took the answers to these questions to her grave.

In 1973, Major David Russell, Pat’s surviving brother, gave Silverburn to the local government and the National Trust for Scotland. A municipal golf links, where the brothers used to play, separates the estate from the beach.

From the golf course the land slopes up a low ridge, at the base of which is the remains of a flax mill built in the mid-19th Century.

There’s a large walled garden with a gate.

There’s a rookery.

There are lawns where you can lie around or play with a soccer ball, as these people are doing.

At the top of the ridge where the land levels out again is the Russell house, unchanged from the picture in my mother’s photo album from the 1930s, except for the boarded-up windows.

There’s a walled driveway that Pat went down for the last time a long time ago.

Pat Russell was 26 when he died. He was six weeks younger than my mother, who died in 2008 at the age of 90. My mother had a full and happy life. How happy Pat’s life was I can’t say, although I bet it was reasonably happy. But it wasn’t full. It wasn’t even half-full.

Andy Rooney, who’d been a reporter for Stars and Stripes in World War II, on the eve of Memorial Day in 2005 said of the soldiers who’d died: “We use the phrase ‘gave their lives,’ but they didn’t give their lives. Their lives were taken from them.”

Like a lot of simple observations, it’s one we tend to forget.

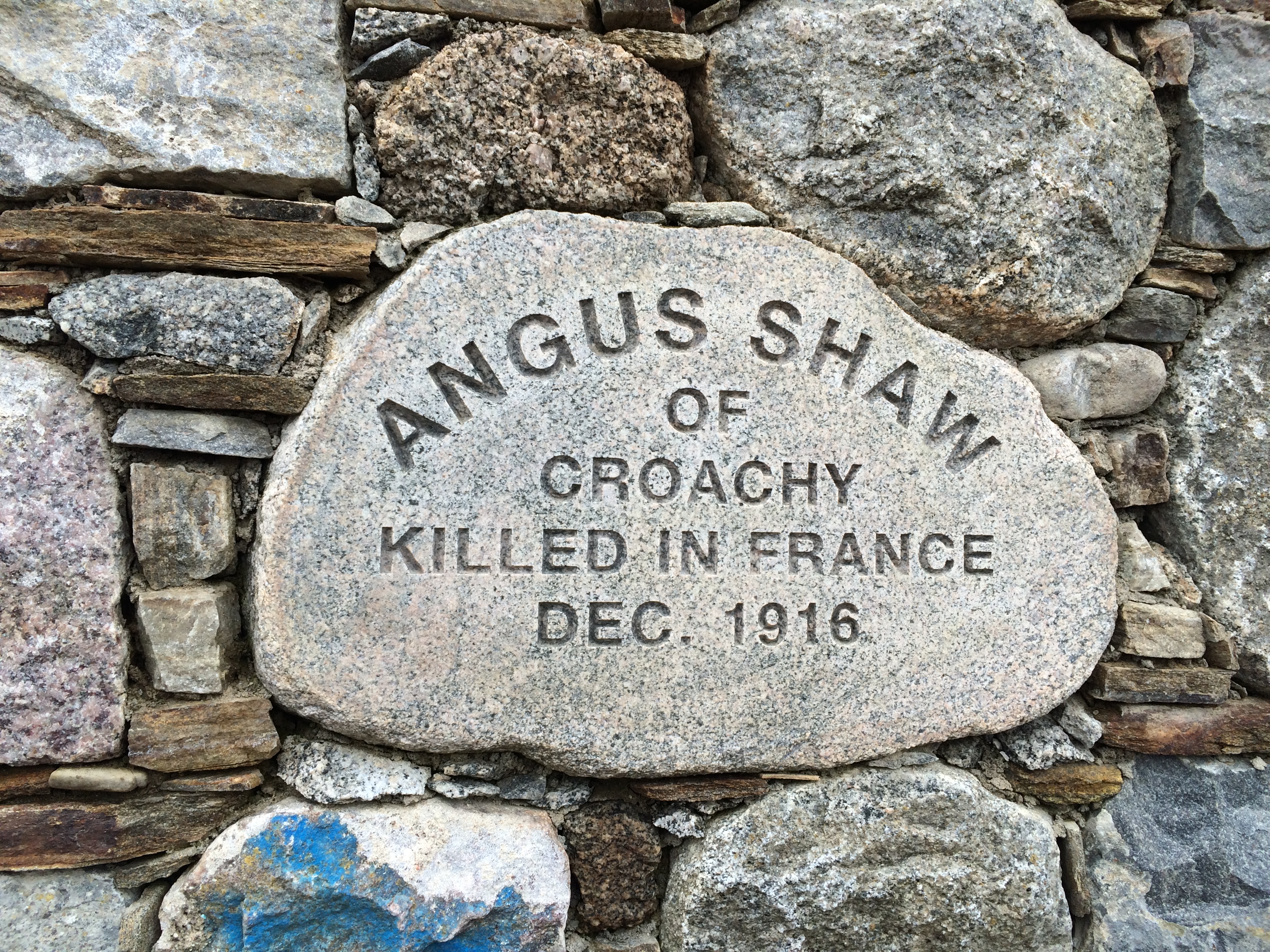

Pat Russell is remembered here, in Fife, at the family burial plot.

But he lies here, in the Gradara War Cemetery, in the province of Pesaro, Italy, not far from where he was killed. There are 1,191 men buried with him.

May neither he nor they be forgotten.

Recent Comments