The last day was by the map the longest of the walk, about 18 miles.

I’d hoped to make enough progress for it to be shorter. Unfortunately, large amounts of time were consumed trying to load, rotate, save, and upload photographs and posts via narrow-band Internet connections. I never seemed to get off before noon–an appallingly late hour, and one by which most Challengers were halfway done for the day.

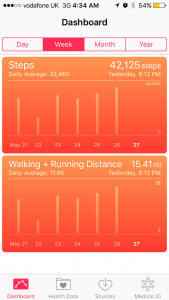

It was also the longest day as calculated by the pedometer I discovered on my new iPhone a few months ago. The average day was about 37,000 steps. The one from Gardenstown to Fraserburgh was 42,000 steps.

I left Gardenstown on the road, as advised by Bob Watt (of the previous post), but hoped to get to the cliff tops eventually. I wanted particularly to get to a point of land called Troup Head that is famous as a nesting spot for gannets, puffins and other exotic marine birds. But there was no easy way to get there, and I was unwilling to do much experimenting. So I left it for another day.

I eventually got to the road down to Pennan, a cliff-bottom hamlet where much of the movie “Local Hero,” starring Burt Lancaster, was filmed. All the guides mention this, and there is apparently a red phone booth there that figures prominently in the story. Many people visit Pennan just to get a photograph of the phone booth. I’ve never seen the movie and didn’t want to go down and back up a steep hill, even without the backpack. So I passed it by, too.

But I did take the time to look around a church for sale at the junction of the road I was on and the one down to Pennan.

There are many unused and desanctified churches for sale in Scotland. I was happy to find this one unlocked.

The pews were numbered.

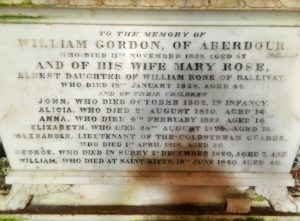

I walked on the road for quite a while, eventually passing a ruined church and graveyard on a road that went to the shore. The gravestones and memorial plaques in such places have just enough information to tell a nation’s story as well as a family’s. Much tragedy is recorded on them. They are hard to read, but repay the effort.

The family that built this chapel, now as empty as a shipping container, had only one child who could be said to have lived to full adulthood.

Here’s a plaque whose commemorated people include a 60-year-old casualty of World War II and an inspector of rubber plantations in French Indo-China.

I could show you more. But I won’t.

I was within view of the shore. I had to cross a lot of fields, lush with emergent hay and animals, to get there.

I got to some new fencing that I found out with my hand was electrified. I thought my trousers might be sufficient insulators to get me over, but they weren’t. But I concluded that like all unpleasant thing, electrified fences eventually come to an end. I made it there, climbed over a gate, crawled under the electrified wire, and proceeded.

I managed to notice without alerting them four fox cubs outside their den under a gorse bush on a bank. I was downwind and able to watch them for 10 minutes through the binoculars. If you blow up this photograph you may be able to make them out. When I started to walk, they noticed me. One of them couldn’t suppress curiosity and looked at me with pointed ears from the mouth of the burrow, finally disappearing.

I found myself between two barbed-wire fences, walking a path I couldn’t change. There couldn’t have been a better place to be trapped.

I passed a house that had the remains of Dundarg Castle and Fort in its backyard.

About six o’clock, I got to Rosehearty, the town just to the west of my destination. (“Just” being six miles.). I hadn’t eaten since breakfast, so I asked a man if there was a place to get a meal. He was on the street, celebrating having just won £50 on a scratch-off lottery card he was holding.

He directed me to a local pub. I had smoked salmon and leek risotto, and moved on. I got to Fraserburgh, and after a little trouble found my way to the guest house where I’d booked a room. It was about 8.30 p.m.

The next day I got up and went to the harbor. Fraserburgh has a commercial fishing fleet. Like Burghead, MacDuff, and some of the other places I’d passed through, it was a no-nonsense, hard-bitten place that was actually more beaten down than it looked. But it at least had a little fishing left, unlike those smaller towns.

I watched two men put styrofoam coolers on a pallet board. Just before a forklift whisked it away I asked the man to show me what was inside.

He called them “crab prawns.” They looked like plain crabs to me. I asked when they were caught. He said, “this morning.” I told him at least he had a bank-holiday weekend coming up. He said: “No holiday for us. If the weather stays good, we’re going out.”

Here I am, on the dock.

I took a bus to Aberdeen, and from there a train to Montrose, and checked in with Challenge Control at the Park Hotel. I was officially done.

I visited with my friends Mark and Carol Janes, whom I had been trailing like an anemic G-man along the Moray Coast. I’d stopped at three places–a golf course bar, a bake shop, and a gas station convenience store–where they’d stopped just hours before.

That evening I had the privilege of eating dinner with Jean Turner and her husband, Allan. Jean, at age 76, was the senior walker of The Great Outdoors Challenge. She is a retired surgeon, as is her husband. She grew up in Portsoy on the Moray Coast, and was most helpful in my research last winter. Allan is a Hebridean Islander and native Gaelic speaker. They are people with great stories.

I hadn’t waded into the North Sea in Fraserburgh. It would have required climbing down a ladder into the oil-slicked water of the harbor. So the next morning I walked to Montrose’s beach and took off my boots.

I walked into the water.

Then I really was done.

Recent Comments