This August will mark one hundred years since the start of the Great War, now known as World War I.

Most historians believe the Great War set the conditions that made the next war, World War II, inevitable. Some believe it was even more important. They argue it established the entire trajectory of the 20th Century, from politics to race relations to music. National Public Radio recently broadcast a series of stories on “counter-factual history” that explored how history might have unspooled in a radically different way if the war had never started. It’s worth listening to:

http://www.npr.org/series/286403203/what-if-wwi-had-never-happened

But of course it did happen.

Germany had at least 1.8 million military deaths, Russia had at least 1.7 million, France 1.4 million, Austria-Hungary 1.2 million, Britain 703,000. Of the 557,000 Scots who enlisted in the British forces, 26 percent were killed.

At the top of Edinburgh Castle is a memorial building for Scotland’s Great War dead. Inside, there is a plaque, relief or window for almost every military occupation or large unit. Accompanying each is a book listing the name, home, death date, and sometimes a little more information, of each of the dead. The building is as exquisite as it is sad. It is so sacred that photographs of the inside are not allowed.

In a park between the castle and the train station there was a statue honoring the volunteers who answered “the call.” At its foot, were wreaths of poppies (artificial in this case), which is the British flower of remembrance.

A relief depicted people of all ages and walks of life falling in behind the soldiers, doing their part. (The Moscow subway is full of similar iconography, except the soldiers it honors are those of the Great Patriotic War, which is the Russian name for World War II.)

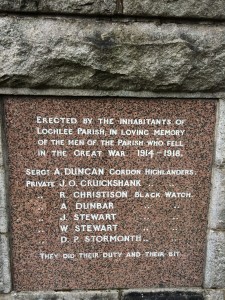

I took some pictures of monuments to the Great War dead during my time in Scotland. This is one I walked past in Tarfside; I wrote about it in one of the posts from the hike. You can click on this picture (and others) to enlarge it and read the inscription. It says: “They Did Their Duty and Their Bit”.

Some monuments are in the middle of nowhere. This one is between Campbeltown and Southend, on the Kintyre peninsula, surrounded by farm fields.

Many are large, elaborate, regimented, and information-dense. This one is in Dunoon, a town with a ferry terminal where I landed on my way to visit Paul and Deborah Richard in Argyll. It honors the dead from the whole Cowal Peninsula. There are 130 names on the left-hand column and 90 on the right-hand column. Paul and I didn’t count the middle two columns.

You don’t have to look hard to find people with the same last names. What the monuments don’t tell you is their relation to each other–if there was one–that might hint further of a family’s loss.

Most, but not all, of the monuments list the dead by rank–officers above NCOs above enlisted men. Some towns and villages objected to this. They wanted the dead listed by name only, with no hint of caste or implied importance. Because many monuments were paid for “by subscription”–with money from contributors–that effort sometimes succeeded. But not here.

Scotland had a huge diaspora in the early 20th Century. Some immigrants fought under other flags. The Dunoon tablet lists soldiers serving in the U.S. Army, the Indian Army, the Australian Expeditionary Force, the New Zealand Expeditionary Force. But they were remembered as Scotsmen. In the lower right-hand corner are the names of two nurses: A. A. Scott and Helen Yeats.

Along the bottom of the tablet are the words, “Death is Swallowed Up in Victory.” It’s hard to know what to make of this sentiment. You have to believe something.

There are private monuments to the Great War’s victims, as well.

This one is at the water’s edge a few hundred yards from Paul and Deborah’s house. They bought the property from a man whose mother had two brothers killed in the war. The monument appears to have been a fountain as well, catching water from the slope behind it. There’s a lion’s head over a giant clam shell, with a copper drinking cup on a chain, at the base. But the water no longer runs.

The brothers died in the disastrous attempt to control the Dardanelles strait and go on and capture Constantinople, the seat of the Ottoman Empire. The campaign failed. Thousands of Australian and New Zealand troops were slaughtered running into machine gun fire. The start of the campaign, April 25, is Anzac Day, a national day of mourning and remembrance in both countries.

For me, the most touching memorial was in Skipness, a village with a row of houses and a church halfway up the east coast of the Kintyre Peninsula. It kind of says it all.

There are three names on the monument, and no ranks. Two of the men have the same last name. Brothers? Cousins? One of them was an immigrant to Australia. But this is where he’s missed.

It has a clock that still runs. The clock guarantees that people will look at the monument every day. It tells them the time, and that life is fleeting.

Recent Comments