Our group is 11, most of them Canadians, which is the nationality of Grant Thompson, the owner and cofounder of Tofino Expeditions. He is leading the trip along with Enrico Carrossino, the Italian guide.

We are not a young group. The youngest clients (or are we “sports”?) are a couple from the Peninsula south of San Francisco, each 55. A couple from Vancouver are in their sixties. Four women, all friends, from various parts of British Columbia, are in their late sixties or early seventies.

And then there’s Ellen, Jim and me.

Grant is 60, tanned with a shaved head; a body double for Yul Brynner. He was an art major in college who got into the marketing end of outdoor gear afterward, while spending much of his time rock climbing and, eventually, kayaking.

When I covered the World AIDS Conference in Vancouver in 1998 I spent a couple of days beforehand in Tofino, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, writing a curtain-raiser story. I took an afternoon off and went on a kayak tour of the local coast, with a short walk in the redwood rain forest. The company was Tofino Expeditions—Grant’s company.

Eventually Grant decided he wanted to offer long overseas trip, not just short local ones. Her bought the company name from his partner and moved to Oregon when he married an American physician. He now runs kayak trips in Canada, Italy, Croatia, Mexico, Brazil, Ecuador and Vietnam.

Enrico, 45, is an ace kayaker, white-water specialist who has cobbled together an interesting career. An Italian, he lives in Lugano, Switzerland. He teaches canoe and kayak skills for the Swiss national sporting center two months in the spring. He has his own outfitting company that specializes in getting disabled people on the water. He also guides custom trips on Swiss lakes and on the Italian coast for the able-bodied. He helps organize and guide several of Tofino’s trips each year. He has two-year-old identical twin boys—Marco and Andrea—who he’s now away from longer than he would like.

Enrico is endlessly enthusiastic, ready to talk about kayaking and Italian history at the slightest nudge.

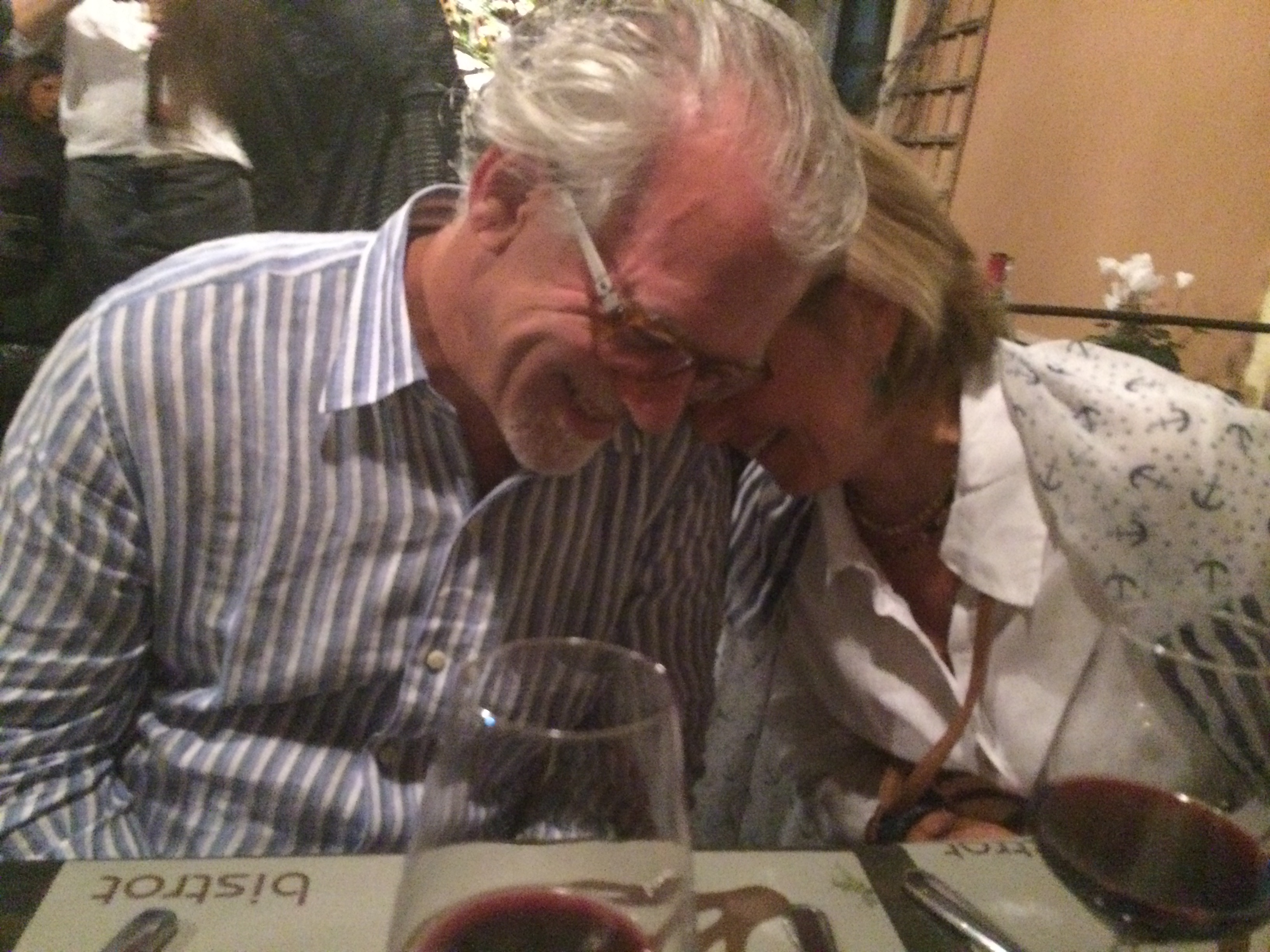

Daniele is 51. He is a childhood friend of Enrico who worked in a factory making air conditioning systems for railroad cars until he was laid off a few years ago. He now works various jobs, including this one. Both he and Enrico are charismatic in an unselfconscious way—friendly, entertaining, authoritative. (Daniele is on the left, Grant on the right.)

The Cinque Terra coast is largely unprotected. Headlands stick out like stubby antlers between the five villages. But basically it’s open sea right from the shore. It would seem to be a risky place to run kayak trips for septugenarians. But Enrico says there has never been a capsizing (although there have been cancelled days for hazardous conditions).

On my first day, however, the conditions were just about perfect.

We had breakfast at 7.30 in the morning and then suited- and skirted-up at the base of the path. (Corniglia is the only one of the five villages without a harbor). We paddled south, most of us in doubles, although Ellen and I were each in singles. The water was calm and deep blue—a color you never see off New England.

Seeing Cinque Terre from the water makes one thing clear one thing: titanic forces created the land we are viewing. The rock is sedimentary, with clear strata but also intrusions. In some places it is slanted at 45 degrees, in other places nearly parallel with the sea, and in others folded like a sheet of filo dough.

In a few places it is vertical, rotated 90 degrees from how it was laid down eons ago.

We paddled close to the shore, which featured man’s efforts over many centuries. High on the slopes were terraces separated by dry stone walls. Once the entire coast was sculpted in a way that would hold its own against any Asian terracing.

But the entire coast is now a study in entropy.

There are places where the terraces are distinct and the plantings they support bright with new growth. There are terraces where the lemon trees and olive trees and grape vines are are recognizable, but whether they are cultivated isn’t clear. There are places where the walls have tumbled, the terracing has begun to return to a perilous slant, and the hand of current man invisible. And there are places where the effort of generations is no longer visible from half a mile distance, although underfoot, with remnants of walls and cultivated plants holding on against the vines, human effort would undoubtedly be evident.

Enrico said that in the 15 miles between the first and the fifth villages there were stone walls equaling the length of the Great Wall in China.

Farther down the slope was a path connecting the towns. The one between Corniglia and Manarola, the next village down the coast, was Via dell’ Amore—The Lovers’ Way. A big favorite, one might imagine, but now closed, and probably forever, Enrico said.

A landslide had taken out three foot bridges a decade earlier. Two million euro-worth of reconstruction—three new bridges and trail improvements—were made before it opened again two years ago. The day after the rededication a flash rainstorm and slide took out one of the new bridges. Three Australian women on the trail were grievously injured. The path is now a wandering place for the ghosts of lovers only.

Closest to the water is the railroad. It was built during the 20 years of Mussolini’s reign. It is hard to imagine the labor it required. Most of the line in Cinque Terre is tunnel; two villages are connected entirely by tunnel. The removal of the stone required to build the tunnels is the reverse equivalent of the piling of the stone required in the terraces above it. Enrico said it is one of the few products of the Fascist era that Italians are still proud of.

We paddled east—down coast—to Manarola, and then on to Riomaggiore, where Enrico made a dinner reservation for the group, shouting from the water to a man on a veranda of white umbrellas.

Riomaggiore is the down-coast border Cinque Terre. We paddled back to Manarola and made landfall. The stone road up from the quay was lined with parked boats.

Most were gozzo, the traditional wooden row boats, lapstrake and double-ended like Penobscot dories but beamier, and with a prominent bowsprit where you can tie a line or hang a life ring. Most have added transoms for outboards on the stern. Although the fish we are eating is touted as local we haven’t seen anything that appears to be a commercial fishery. The people in these boats had fishing rods only.

Enrico disappeared and reappeared 15 minutes later with fried local sardines, calamari, bresaulo (which is a kind of beef prosciutto), cheese, bread and french fries. We had not done remotely enough exercise to warrant such a meal, but that seems to be the way of things on Tofino Expeditions. This is a food tour as much as a paddling trip.

After lunch we had an hour or so to explore. Ellen and I went up hill to where the road led to footpaths into the terraces. We climbed to some that were under extremely laissez-faire cultivation. Some of the terraces had stone bunkers, their purpose unclear.

We had a good view of Manarola.

We made our way back to Corniglia over the indigo water. For dinner we took the train back to Riomaggiore to claim our reservation.

To kill some time five of us walked to the top of the town, where there was the remains of an old fort and a piazza with a cross and a view up the coast.

At the very top was a parking lot; where the road to it went was unclear. A man there was guarding boxes of green grapes. A younger man, whom we’d passed on the walk up, was carrying the boxes down the stone road to a room we’d peeked into where a man was preparing to crush the grapes.

Earlier in the day we’d seen large photographs in Manarola of people carrying baskets of grapes down the stone paths and stairs from the terraces in the 1940s and 50s.

We had a great dinner, of course. We took the train back to Corniglia. Ellen was dressed as if she were a member of the family of Saltimbanques.

Recent Comments