Sunny days in Scotland are always living on borrowed time. The sun shone the first week of The Great Outdoors Challenge with such intensity that to some people it seemed like an unnatural event.

Whenever I’m in a situation in which every minute of good fortune is a further defiance of the odds I think of the last scene in “Moby-Dick.” The worst has happened, the voyage has ended in catastrophe, and everyone except Ishmael is dead. He’s saved by Tashtego’s coffin, which he uses as a life raft, waiting for rescue. Around him, Melville writes, “the unharming sharks, they glided by as if with padlocks on their mouths; the savage sea-hawks sailed with sheathed beaks.”

The locks and sheaths eventually come off. And so it was here the last couple of days.

I left the village of Fortingall in what, in my experience, is a typical Scottish rainstorm—light, not wind-driven, long lasting. I was unfortunately on a stretch of the route that required road walking, which isn’t that much fun in the rain. Nevertheless, there are always things to see, such as these two horses, who ran around the field as if yoked side-by-side.

I passed gallery run by a man who used to be a carpenter (“a joiner”) building houses, but who now made welded sculpture from found objects. Here’s some of the stuff waiting to become art.

I walked along a river and came to a house that was open and appeared to be owned by a fishing club (which it was). Nobody was around to ask whether I could use it for a lunchtime shelter, which I did. A club member eventually showed up and said it was okay.

I got off the fields and away from the stream valley and headed upward into a pine forest. There are small areas of natural woods in the Highlands, but most of the trees in this part of Scotland are planted monoculture. The pine pollen was rafted up in puddles on the ATV track I was following.

The road led to a high, clear-cut area where wind turbine blades turned slowly with barely audible groans.

In one place the towers were hard-by the remains of a small settlement, a study in technological achievement centuries apart.

Walking along the track I passed two puddles that appeared to be stained with blood. In one, the pollen had made a chalk-like outline around it, suggesting a crime scene. I wondered what had happened.

A few steps later I came across more evidence, but no answer. It looked like the opening scene of a police procedural on British television about a murder in an unexpected place.

A planting of non-conifers ran through one clear cut, each sapling protected by a cage.

The pine forests are completely unnavigable, except on hands and knees. They are also a lot darker than this picture suggests.

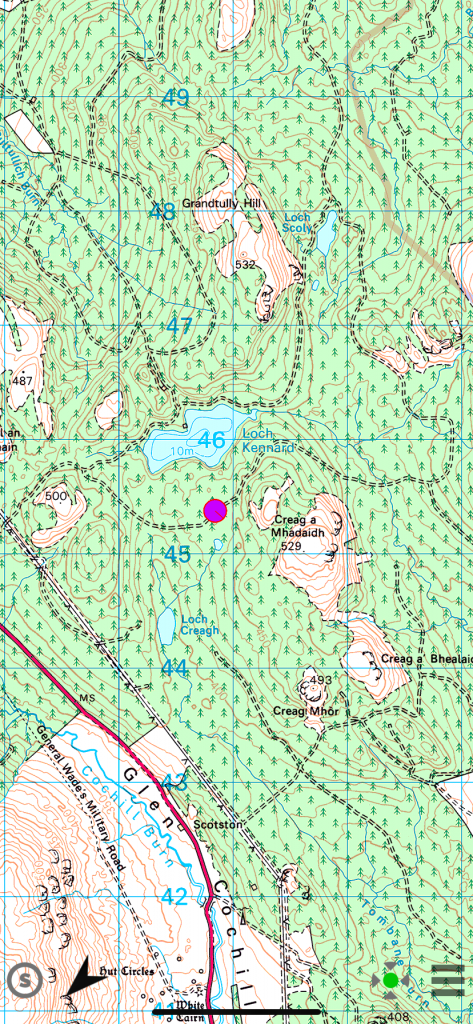

I finally stopped, again slightly short of where I’d planned to. I was tired, wet, and it was after 7. The purple circle marks the spot—the middle of nowhere.

The bits of cleared ground off the road were boggy and bumpy. The best campsites were in sections of wide shoulder—“verge” over here—next to the road. I picked one that had a tree sticking into the roadway, from which I hung the pack cover to warn of my presence. It seemed unlikely, however, there’d be any lumber trucks coming through over night.

Camping in the rain is an art. You need to get the tent up quickly and everything under cover, while not simply chucking everything into the sleeping area and getting it wet too. At the same time, you need to bring some things in there to help them dry out overnight. A few honored guests, such as wet socks and wet boot insoles, are eventually invited into the sleeping bag for the night.

I had one full water bottle. I used two-thirds for dinner and saved enough for coffee in the morning. It was an odd situation—to be wet, in the rain, and having to ration water because there was no stream or loch right out the door.

I went to bed before it was dark and listened to the calling of cuckoos and other animal through the night. Dangerous animals—bears, wolves—have been gone from Scotland for centuries. Nevertheless, it’s always a little disconcerting to be alone on a road all night long.

So it was with surprise that I heard the rhythmic sound of footfalls the next morning as I finally summoned the willpower to pull myself up to start the day.

I looked out the open tent flap and saw a woman running down the foggy road with a black lab on a leash. The dog was about as heeled over as he could be trying to get a good look at and smell of me as she ran by.

“Unbelievable,” I said out loud.

“Have a great day,” she said.

Getting things done inside a tent—putting on pants and socks, for example—requires a crude form of yoga that can be uncomfortable for a sore body that hasn’t gotten a good night’s sleep. This is especially true when don’t want to go outside or disturb the tent and send a rivulet of rainwater onto semi-dry objects. Have you ever tried making breakfast in pigeon? It’s not easy.

I packed up everything and got outside to strike the tent, the last thing to do before moving on. I was out of water, of course. But I found the pack cover-hazard sign had accumulated a small pool over night, just enough for brushing my teeth.

I instantly felt better. I put on my mittens and hat—it was cold as well as wet—and headed down the road.

Pleasure or penance? Hard to tell.

I hope more borrowed, sunny weather is in the forecast — preferably a loan charged without interest. The pine forest, judged by the photo, seems truly forbidding.

Sorry I commented on your lovely weather. No doubt that brought on the rain.

That rain looks awfully familiar, in a Scottish sort of way. Any hint of snow?

Hope the weather improves for your last few days David! Fascinating trip and guide book …hope to join you in Spain for the Way.