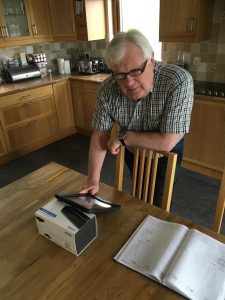

I was the only guest in John Ross’s B&B, which he operates more or less when he wants. He makes money installing closed-circuit TV systems. His wife died a dozen years ago and he lives alone. His four children–all boys–are long out of the house.

He also plays the guitar, banjo and mandolin, and is the creator of a weekly live-music night in Ardersier, a village of about 1,500 people. Unfortunately, it was the night before I arrived.

On the wall of his kitchen are photographs of relatives going back several generations. One of them was an uncle, Donnie Ross. He was a sniper with the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders during World War II. He was one of the 10,000 members of the Highland Division that surrendered in St. Valery on the French coast near Dieppe, on June 12, 1940, when it was clear a Dunkirk-like rescue wasn’t possible.

He survived transfer by foot and cattle car to Poland, and then five years as a prisoner of war. He might not have survived the first day, his nephew said, if a fellow soldier (also from Ardersier and also named Donnie Ross) hadn’t thrown his friend’s sniper rifle in a pond and cut the sniper insignia off his uniform. Otherwise the Germans might have shot him on the spot.

Donnie (the uncle) had been a farmer, and worked on a farm in Poland. “That’s probably the other thing that saved him. There was more food,” John said. Every five years, he returned to St. Valery to reunite with other survivors. He died a few years ago in his upper 90s.

With military matters in mind, I headed out in the drizzle once more, with the destination Fort George, an 18th-century fort at a headland two miles to the north. It’s a historical site and also an active garrison, with a small number of soldiers still stationed there. It was built after the Jacobite Rising of 1746 and has never been under attack.

It’s beautifully maintained.

Out of the rain under an arcade I met Glenn Lawson, who was putting the final paint job on a WOMBAT anti-tank gun, one of the few left in existence. It has an American-made 50-mm spotting rifle (which fired phosphorus-tipped tracer bullets) mounted on top of a 120-mm artillery piece.

He’d retired from the British Army as a sergeant major after 25 years of service. He was one of the last people to fire the gun, in 1986 when the British military installation in Belize was closed. Seven WOMBATs were dumped in a lagoon by helicopters, and this one was taken home for historical purposes. It had spent much of the last three decades incorrectly assembled and out in the weather.

This was Lawson’s fourth trip up from his home in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in England, to work on it. He was almost done.

By this time it was mid-afternoon and I’d hardly started walking. So I turned in the audio guide, left the fort, and made my way to the beach.

Almost immediately, I came across what I believe is the remains of a pillbox, part of the network of defenses built along the northern coast of Scotland during World War II. I expect to see more of these.

The tide was out. The views were beautiful. My feet got wet.

On the outskirts of Nairn, my destination, I had to cross an annoying stretch of bogland between the beach and high ground. I was glad to finally see this.

The caravan park and campground was on the far side of the village. It wanted £17 to pitch a tent. That seemed a bit high, so I staggered on, out past the wastewater treatment plant to the dunes east of town and found my own place. It was again after 8.

Binge-reading Brown’s Blog… A wee dram of wonderful.

“First-strike status” is an alarmingly appealing new way to think about parts of the urban landscape. The story of Donnie Ross more than makes up for the bogs and rain, at least for this reader.