Before each of my treks in The Great Outdoors Challenge I’ve stayed in a hotel one block west of the Glasgow School of Art. My first year, 2014, I also stayed there for a night after the walk. When I arrived back, the streets around the school where cordoned off and crowded with fire trucks and cranes.

Glasgow’s most famous building had burned while I was away.

The Glasgow School of Art Building, finished in 1909, is the masterpiece of Charles Rennie Mackintosh who, with a few others (including his wife, Margaret), invented the “Glasgow Style” just before and after the turn of the 20th Century. It epitomized the city’s ascendancy as a center of design and craftsmanship in the era of Art Nouveau along with its older identity as a builder of ships, bridges, and heavy machinery. (And to drive home that analogy, consider that Glasgow launched more new-vessel tonnage in 1913 than either Germany or the United States.)

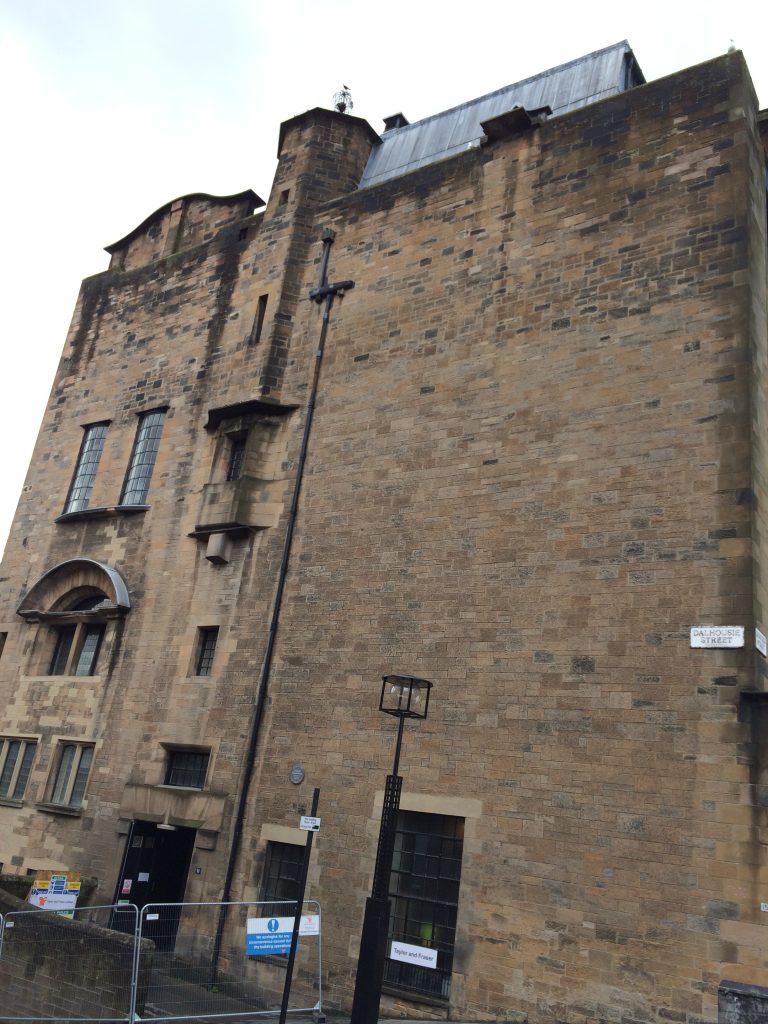

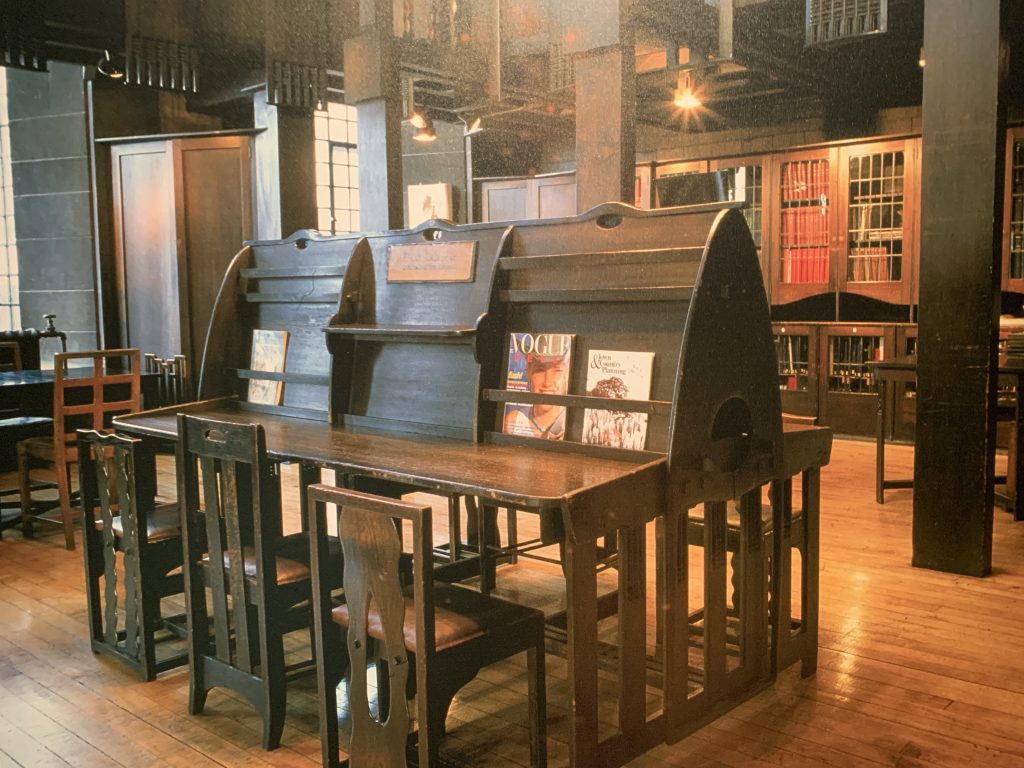

Now known as the Mackintosh Building, it housed classrooms, studios, and work rooms. The east end had an oversize door through which circus animals were led into a studio where students could draw them. In the cavernous library of dark wood, every appointment–chairs, tables, shelves, desks–had been designed by Mackintosh.

The fire, which destroyed the library and about 30 percent of the building, shocked Britain’s architectural community, and especially the graduates of the School of Art.

One of them, Clare Wright, wrote of the building: “For many, especially those of us who experienced our adolescent creative coming-of-age there, it is like a parent . . . It validated our creativity and moulded our architectural outlook irrevocably. It was the powerful presence we could kick against and throw paint at, climb over and revel in, which it seemed could not easily be damaged, even by 100 years of teenagers’ artistic mess. It had places we could go to be calmed and soothed.”

There was little debate about whether to rebuild it, although everyone agreed the work would take years. Money was being raised within days of the fire, which investigators determined started when flammable gases from an aerosol can were ignited by the hot bulb of a projector.

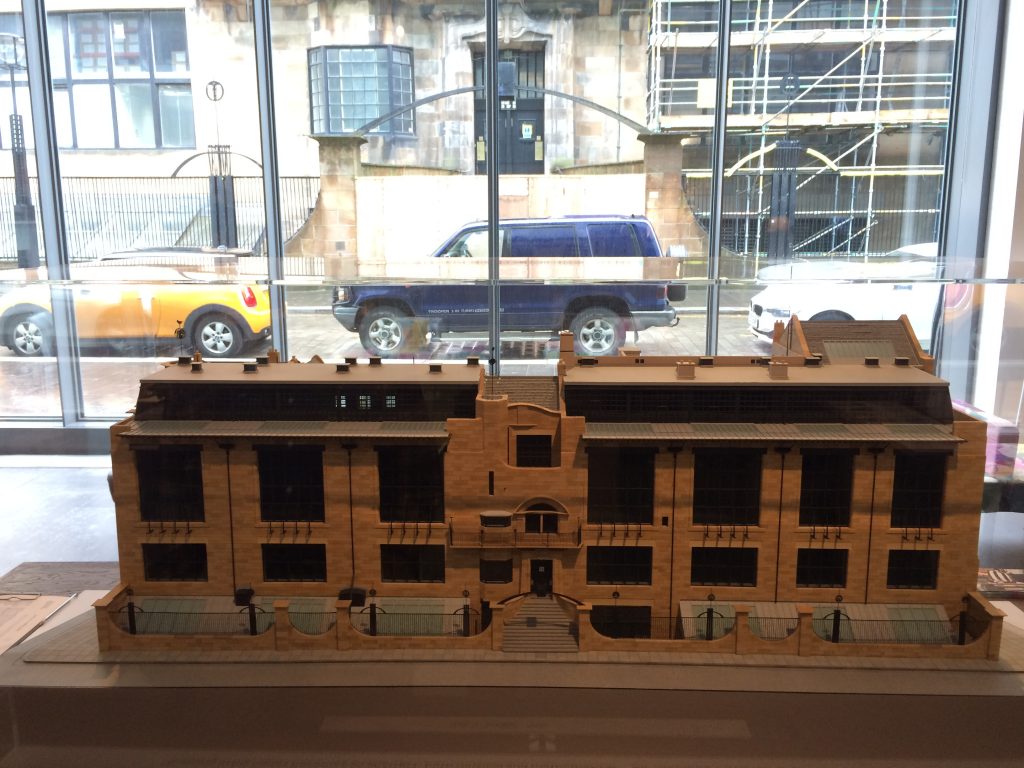

Here is a model of the building, with the real thing through the window across the street.

Here are two pictures I took in 2014, a few days after the fire.

When I returned in 2015, barriers were still up the and rehabilitation was underway.

Then on June 15, 2018 the unimaginable happened. The building burned again. This time it was much, much worse.

Early press reports were that 80-90 percent of the building was destroyed. The roof collapsed. The building is on a hill and the downslope facade was rendered unstable and eventually had to be taken down. Both the east and west facades were also damaged, but not irreparably.

The Glasgow School of Art had allocated £49 million for reconstruction after the first fire. The second one destroyed £24 million in restoration work.

A fire suppression system had arrived at the site a few days before the fire but wouldn’t have been up and running for months. The one fortunate thing was that architectural features and furniture salvaged after the first fire were in storage and safe.

The school and the lovers of the building vowed it would rebuilt. Repair was no longer the right word.

“Beyond that it is too early to say much,” the School of Art press person, Lesley Booth, told me in an e-mail. “You will appreciate there is a complex mass of permissions that will be required before we can actually begin the process of the rebuild.

“In terms of cost, about which there is much speculation, again it is too early to assess what this is likely to be, but we were insured and it is our aim not to take any public money for this project.”

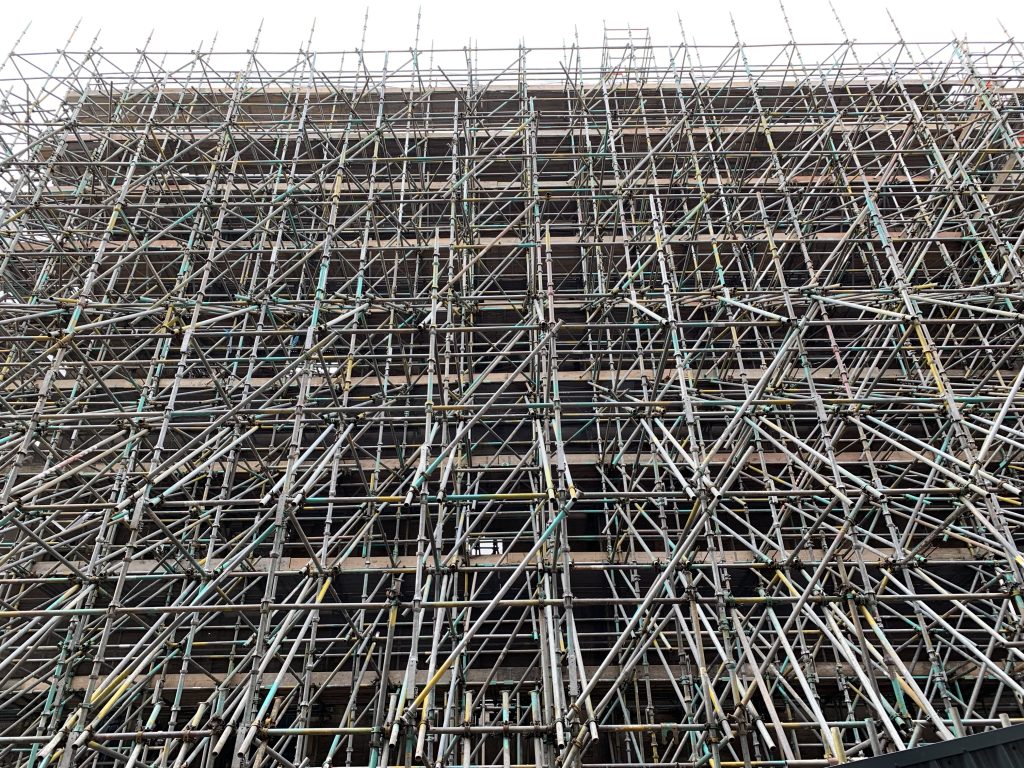

This is what the west end looks like now.

And the east end.

More than 450 tons of “retention scaffolding” has been erected to stabilize the walls. In places it’s turned the Mackintosh Building into a piece of environmental art–Christo goes tubular.

Glasgow, in fact, appears to be in a frenzy of rehabilitation. Walking one evening I passed another building, itself a piece of art.

The cause of the second blaze is uncertain, although it too has been declared an accident. Miraculously, nobody was injured in either fire.

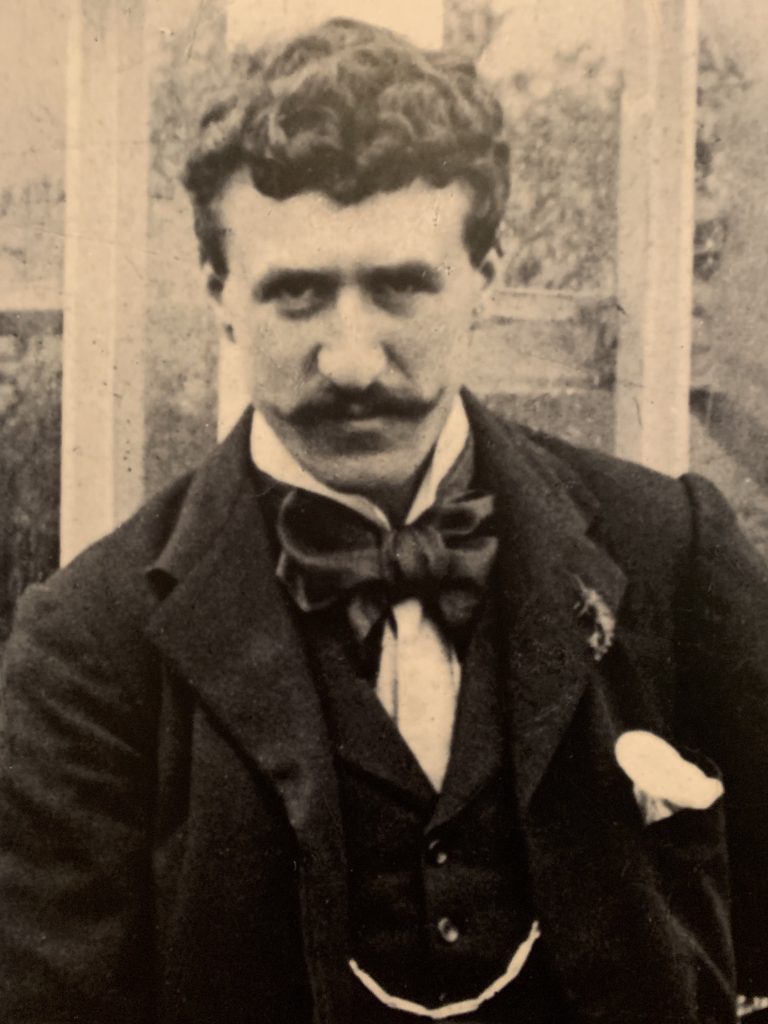

Needless to say, with or without his building, Charles Rennie Mackintosh lives on.

This is the reconstructed Willow Tea Rooms where I had a 1,000-calorie snack a few days ago. Mackintosh designed four tea rooms in Glasgow, down to the dishes.

One floor above is his Chinese Tea Room, a fusion of east and west.

Time will tell whether the Mackintosh Building’s library will be reconstructed. Detailed drawings and laser-based measurements exist, so it’s possible.

There are several Mackintosh buildings in and around Glasgow, and an extensive collection of architectural sections, furniture, and art at the Kelvingrove Museum and the University of Glasgow.

One can’t do justice to Mackintosh’s indiscriminate genius, so I won’t try. Here are a few of his pieces of furniture, at the Kelvingrove.

And here, a decorative architectural panel, done in collaboration with his wife, Margaret:

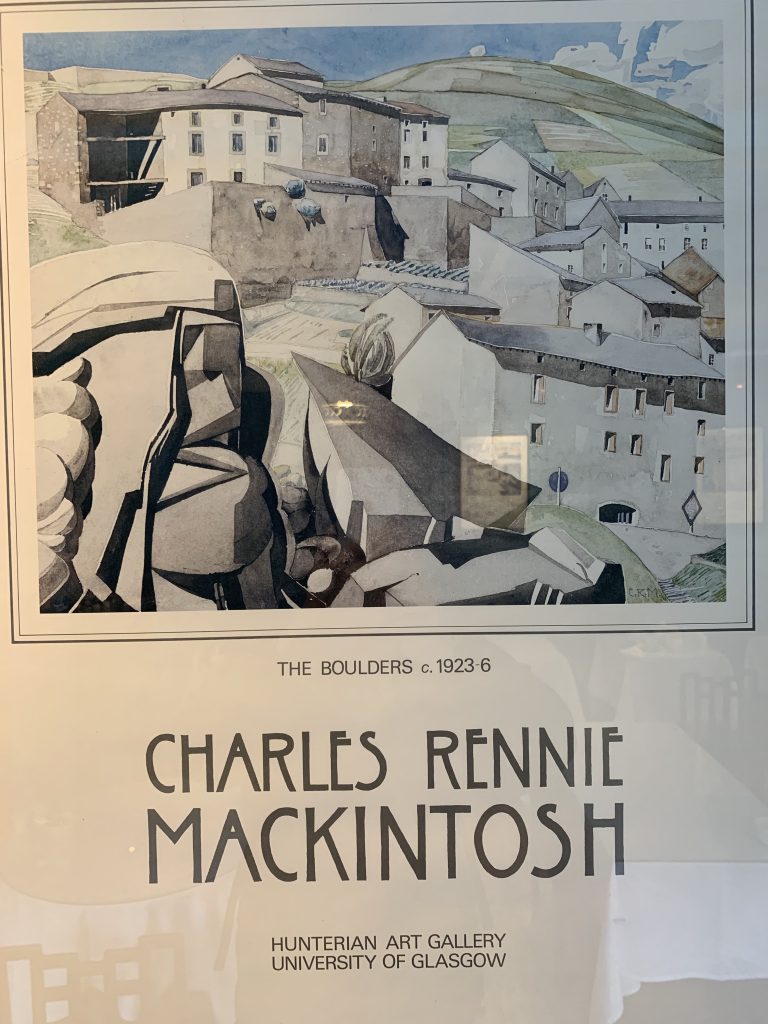

Mackintosh spent the last decade of his life in Southern France, mostly painting.

Mackintosh’s output was prodigious and first-rate across many disciplines–Leonardoesque to a degree. Nevertheless, he died in 1928 at age 60 relatively unknown and not wealthy (and also childless).

In biographical materials much is made of the fact that Mackintosh had a serious drinking problem much of his life. Although not to embrace that, it does bring to mind Abraham Lincoln’s supposed comment about General Grant’s drinking: “Find out what brand of whisky he drinks so I can send a case to my other generals.”

Residents of Baltimore and its environs may be happy to learn that the Walters Art Museum will be one of three American museums to host “Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making the Glasgow Style,” a show with more than 250 objects now touring the world.

It will be in Baltimore October 6, 2019 to January 26, 2020.

Tubular Christo seems as engaging as the most recent, genuine Christo, made of stacked metal barrels. If you have room in your backpack, I would like four — no, six — high-backed Mackintosh chairs.