I was awake until 1 a.m. uploading posts, which probably wasn’t the best way to prepare for the first day of my walk around the Cairngorm Mountains.

The Cairngorms are Scotland’s biggest mountain range (although the country’s highest mountain, Ben Nevis, is not in them). They are Scotland’s winter playground and the main ski destination. One of Scotland’s two national parks is in them.

The Cairngorms are like New Hamphire’s White Mountains–not terribly high, but with changeable and unpredictable weather, and a history of death among the ill-prepared and unlucky.

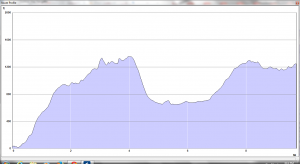

I had to buy stove fuel and mail a package in Aviemore, where I’d spent the night at a B&B, so I got a late start. It was almost noon by the time I headed east down the road toward Coyluymbridge and Glenmore and then into the mountains.

I took a cycling and walking path called the Old Logging Road that paralleled the auto route. It was flat and pretty nice. I passed a clay pigeon shooting range, a sledding area, a reindeer park, a cycling trail, an orienteering area, and the visitor center for the park. The last outpost of civilization was the National Outdoor Training Center, which is a place where you can spend nights and get instruction in various mountaineering sports and skills. It was about 2 o’clock and lunch service had stopped. Sale of “bar food” (as the sign said) wouldn’t begin until 5. I asked a friendly woman at the desk of the center whether there was any way to get hot food. Not unless I walked back from where I’d come from and went to the cafe at the park visitor center.

Of course, by then it was raining. The prospect of walking back 15 minutes (even without my pack), spending at least 30 minutes getting lunch, and walking back to where I was just didn’t seem worth it. I knew I had a long way to go. So I settled for two small packages of potato chips (“crisps”), then shouldered up and headed on.

It was the usual two-rut track, climbing slowly and eventually turning more stony, which is hard on the feet even through hiking boots. The road briefly turned downhill and crossed a stream. Three tents were set up. Two were closed. In the entry to the other was a man working on his feet. He didn’t look up and I didn’t stop.

The trail became steep. The wind picked up, blowing straight out of the west along the backside of the first rank of high mountains. I put on more clothing.

The higher I climbed, the harder the wind blew. The steeper the track became, the harder the wind blew. It was directly into my right side and a few times it made me stumble sideways. It was cold. But at least it had stopped raining.

I flushed two grouse, who must have been very disturbed by my presence because it was no weather for flying. On many tracks this year I’ve flushed one (or, more often, a pair) every couple hundred yards or so.

A peculiar attribute of these round-top hills is that you can rarely see the top from below. In practice, that means that when you get to what appears to the highest spot it turns out to be only the brow of a ridge. There is another ascent, set back just far enough to be invisible from below. That was the case on this climb. It went on forever.

I got the pack down and put on a fleece hat and mittens. It was in the low 40s or high 30s. The cold drained the battery on the iPhone, so there aren’t many pictures.

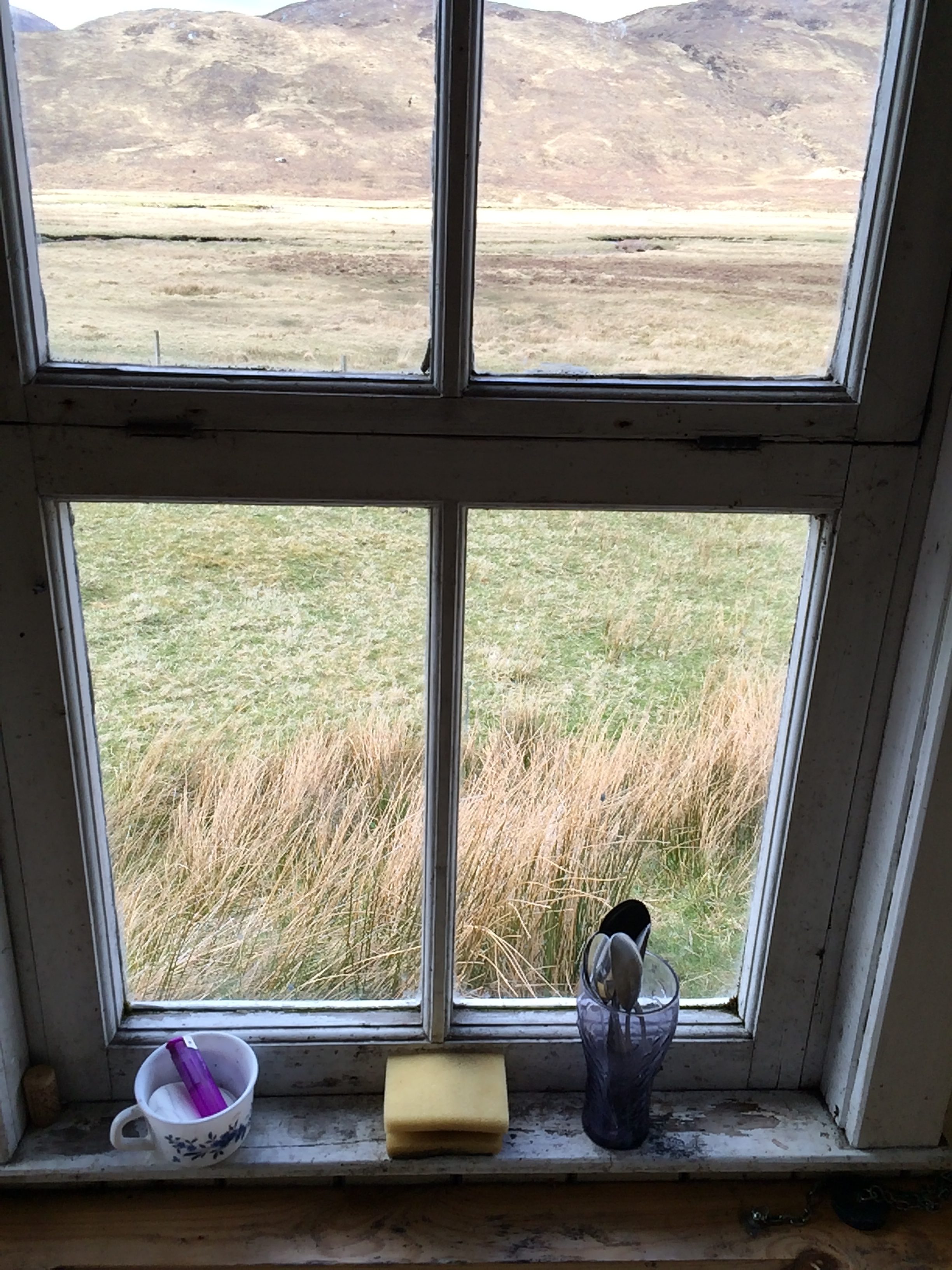

Finally, the ground leveled off. To the west was the knife-edge ridge of mountain whose top was in the clouds. Undoubtedly, in the right conditions some Challengers would peel off and climb it. But not today. The track was littered with pink granite boulders. The grass tussocks were blown flat.

The track headed downhill. I was hoping the bottom would be the Fords of Avon, which was my destination. But I hadn’t looked at the map closely enough. I had another climb. And it was clear as I descended that the stream at the bottom wasn’t big enough to warrant a name on a map announcing it was fordable.

The ascent wasn’t nearly as steep, but it was directly into the wind. There was a hidden summit, but only one. Then a descent with a hidden bottom. But finally I saw a river and three green tents around a pile of rocks on grassy mound.

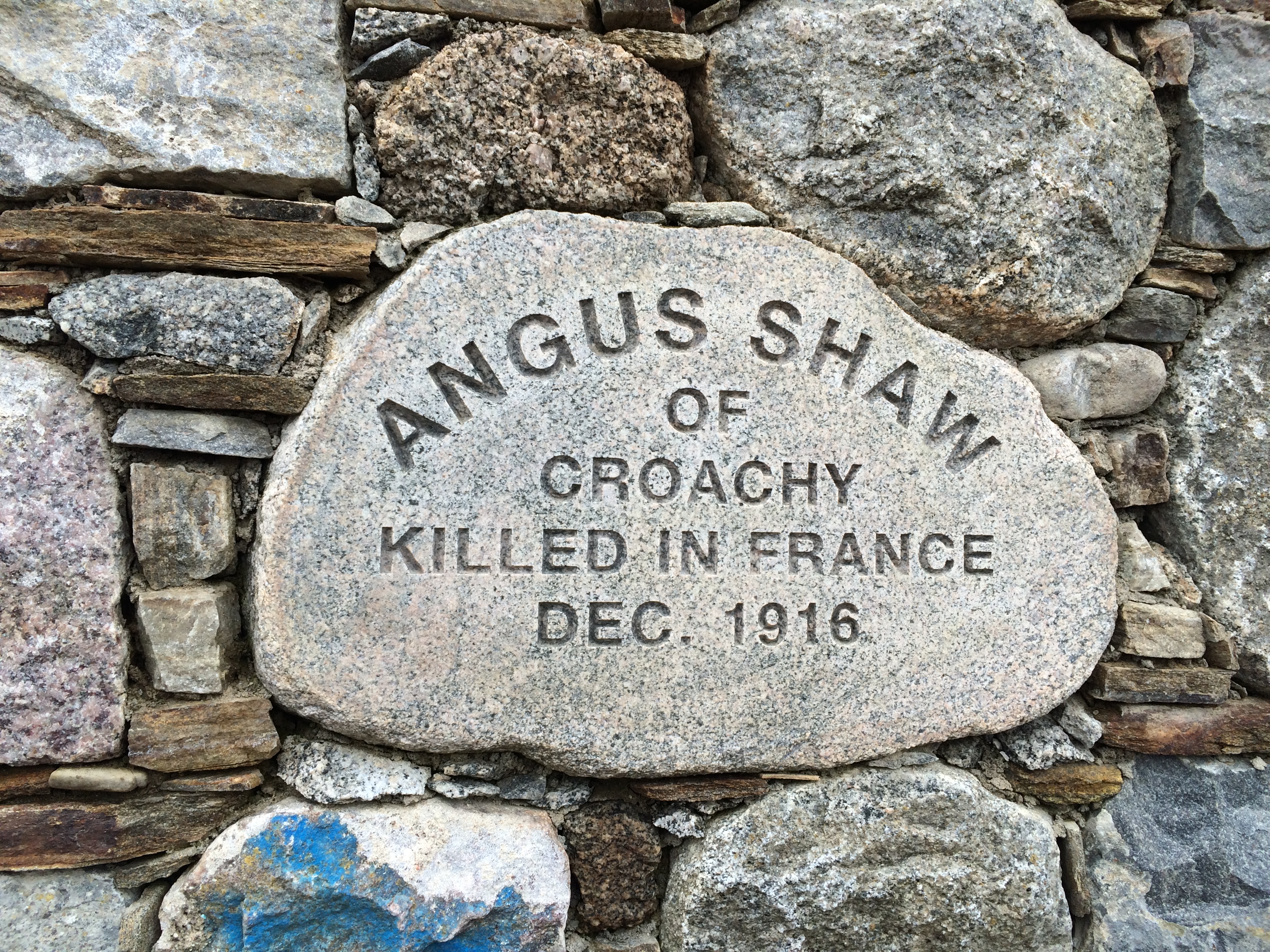

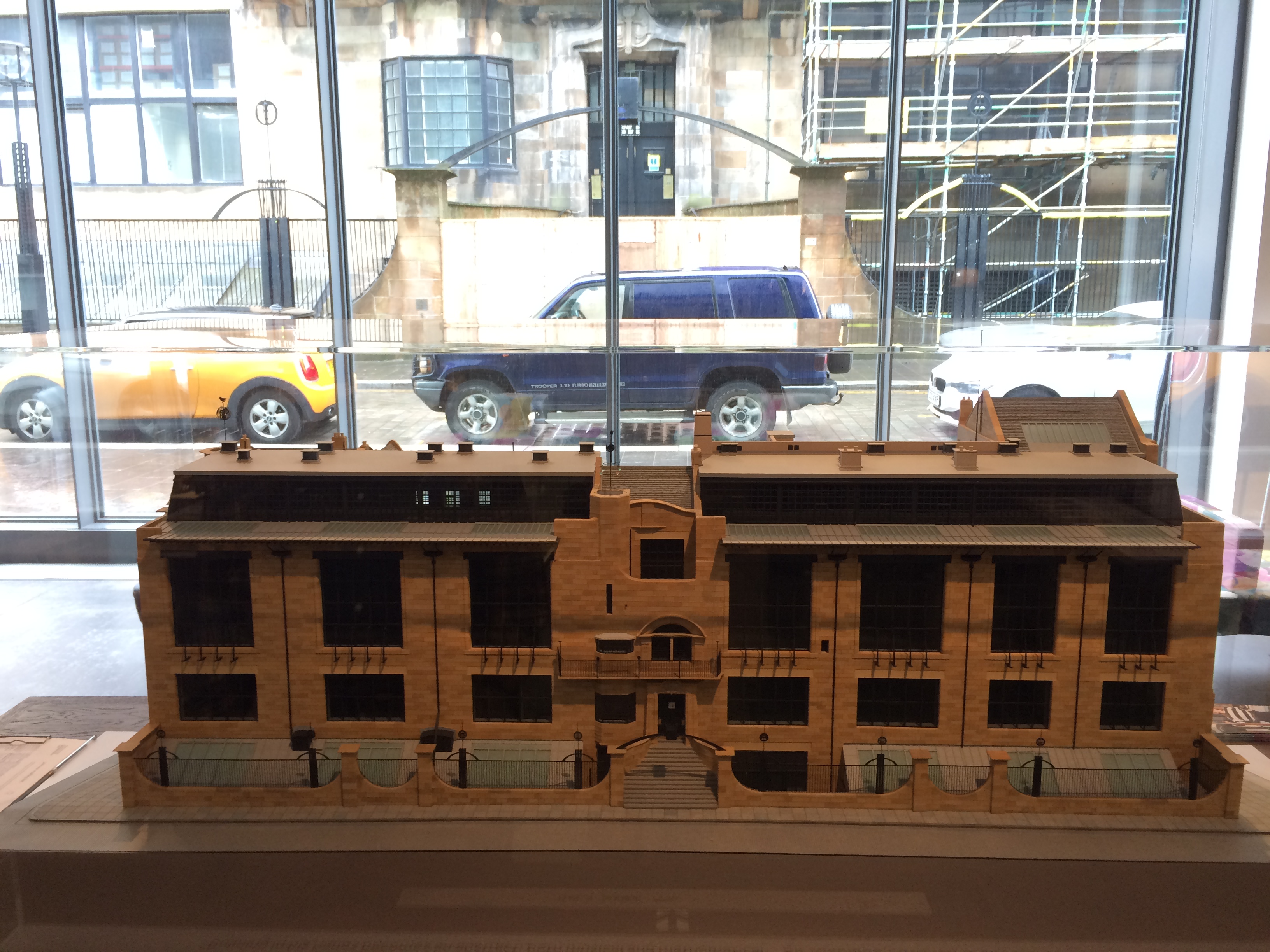

The rocks turned out to be the buttressing of a “refuge,” which is a wooden box about one-third the size of a shipping container and not tall enough to stand up in. It contains nothing but a logbook, a dust broom and two shovels. It is meant to be emergency shelter for hikers and skiiers–enough to save a life, and nothing more.

I looked inside and saw a man and three women, who had stoves out and had finished cooking and eating. It was raining again. I exchanged a few sentences with the man about the wind at the top. He estimated it at 50 mph, which was my guess.

It was difficult to set up the tent, which I put close to the rock pile, although I was not truly in the lee. I brought my stove and food inside the refuge and made dinner. The man by then had retired, but the two women were still there and we introduced each ourselves. They were Stella and Viv. They soon retired.

By the time I was on the tea course, however, they were back in the refuge. The wind had plastered the fly onto the roof of their tent, and water was working its way under and into it. Plus the floor wasn’t waterproof. They decided to spend the night in the refuge.

So we talked because it was a little early to go to bed and there was nothing else to do. But then what’s better than talking when you know nothing about the person you’re talking to?

Both the women are from Devon, in southwest England. They met in 1982 when they both became Hash House Harriers, which is a kind of running, eating and drinking activity.

Viv Horton, 70, was a retired teacher of social work at the University of Plymouth. Stella Rasdall, 69, is a nurse, was one of the first hospice nurses in England (back in the day of Brompton’s cocktail) and is now a counselor in a primary care medical practice. Both are on second marriages, with their own children, step children, and grandchildren.

Stella on left, Viv on right.

This is their first Challenge, although like so many Challengers they have a long history of hard and daring activity behind them.

Viv, who has a sharp eagle-like face, worked in Kazhakstan in 2000-2002 for Voluntary Service Overseas–Britain’s equivalent of the Peace Corps. She did “community development” among women with dependent children living in dormitories of factories that had closed down after the collapse of the Soviet Union. About half were ethnic Russians, the rest Kazakhs and Uzbeks.

When she was finished, she and another women bicycled from Kazakhstan to Northern Italy (with a train trip througfh Uzbekistan, which was considered unsafe). It took two and one-half months, and was done, Viv said, to help them process what they had done and to ease the return to the developed world (“as it calls itself,” Viv noted). Stella joined them in Istanbul, and pedaled with them to Thessalonika, Greece.

Stella’s husband had done the Challenge in 2003. Viv and Stella had come to Scotland to do some hillwalking last year and met some Challengers. Stella proposed they do it together.

“I hold her entirely responsible that I’m stuck in a hut on a cold night,” Viv said.

Inevitably, we talked about why a person would decide to do this. Not surprisingly, like most Challengers I’ve met they gave thoughtful answers.

They stipulated the walk was hard. Viv said she’d passed part of that day thinking of people who had harder and unchosen (or semi-chosen) physical trials. Prisoners of war forced to march or work when they were ill and starved. Solo sailors going around Cape Horn and being dismasted.

“It is extraordinary the resilience and tenacity and perseverence that people can bring to bear,” Viv said.

“There is also the ‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light’,” said Stella.

“And older people can be quite competitive,” Viv said.

“In a way, you’ve got more stamina when you’re older, or more determination, more patience,” Stella said.

“And you have the kind of confidence that things will work out that comes with age,” Viv said.

I asked about this.

“If you’re essentially an optimistic person, and have gotten to a certain age, you’ve had all sorts of ups and downs. You realize you’ll be okay. That you’ll be warm and dry.”

This is an interesting and even profound observation. At the least, it’s a good explanation for why the Challenge appeals to so many older people.

I thanked them for talking to me, and retired to the tent. It blew a gale during the night. The nylon fly rattled against the tent roof with a metallic sound.

When I got up all the tents were gone except one, which was empty. Just before I left it started to snow. Just to show who was boss.

Recent Comments