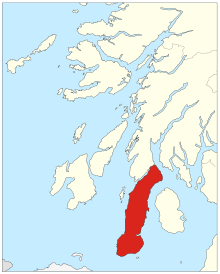

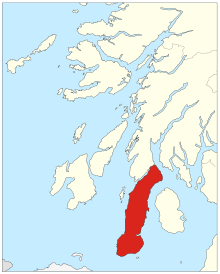

I spent a two nights and three days exploring Kintyre, a peninsula on the west coast of Scotland that hangs like a flaccid circumcised penis over Ireland.

This time I wasn’t going to walk and I wasn’t going to camp.

I borrowed a bike from two of Paul and Deborah’s friends–Fiona and Pieter–who live up the road from them in Colintraive, on the Kyles of Bute. They are an Englishwoman and a Dutchman who chucked fast-lane jobs in Switzerland to become felters in Scotland. They use local wool to make felt for practical (blankets, rugs, vests) and decorative (lampshades, wall hangings) purposes.

I booked nights in a B&B and a hotel, traveling light in an overstuffed day pack. I brought the binoculars this time.

Deborah and Paul drove me and the bike to Southend, a village at the peninsula’s meatus. We had lunch and then drove up to the top of a headland called the Mull of Kintyre. Paul McCartney and Wings had a hit song of that name in 1977; Sir Paul has owned a farm nearby since 1966.

On a clear day you can see Ireland from the mull, but when we were there the top was in a cloud. We walked out of the cloud and down the other side a short distance to get a glimpse of the lighthouse, built in 1788.

I was going to ride down the hill back to Southend, but it seemed unwise on a foggy day (and on a one-lane road). So my friends deposited me on the flat and headed home. I rode back to Southend to explore.

The biggest building there by far is the unoccupied Keil Hotel. It was finished in 1939, and before it could open the British government requisitioned it as a Navy hospital. It was also painted white as a navigational aid, as many of Britain’s lighthouses were extinguished during the war. The five-story building opened as a hotel in 1947, closed in 1990 and was stripped of pipes, wiring, etc. An attempt is underway to renovate it but it’s right on the verge of being a lost cause.

Looking the other way you can see Dunaverty Rock. It is the site of a castle built by Vikings in AD 712 and where the Scottish King Robert the Bruce sought refuge in 1306. It was the scene of various battles, sieges and massacres.

The most notorious was in 1647 when an army of Covenanters blocked the water supply to the castle to force the surrender of a garrison loyal to the English king. In one version of the story, the 300 people in the castle were promised “quarter”–protection and mercy–but were killed, including the women and children, when they surrendered and gave up their arms. The Covenanters were reportedly convinced to spare the life of one boy.

Some were thrown off the rock into the sea.

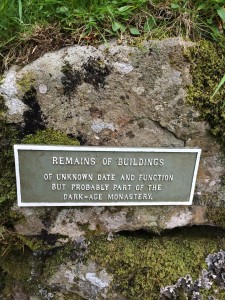

Very little of the castle exists. But there’s a sign testifying to how much progress the place has made in the last 400 years.

I rode out on a 125-year-old golf course next to the castle to see a standing stone that was marked on the map. I haven’t been able to find out much about this particular one, but many standing stones go back as far as 3000 BCE. As I was looking around it occurred to me I could play golf on this trip, too. What an opportunity–hitting the pill around a links course that has a prehistoric monolith in the rough!

I stopped at the clubhouse, where the man running the shop, Jim, was vaping and shooting the breeze with a couple other guys. There were only a couple of groups on the course. He said the full kit–a set of clubs (“I’ve got some really good ones, if you’re left-handed”), a pull “trolley” and the greens fees–would be 36 pounds, roughly $55. It was too late to play that afternoon. As I rode the 12 miles back to Campbeltown where I was spending the night, I tried to figure out how to fit it in.

One of the things I wanted to do was tour a distillery in Campbeltown, where three brands of single-malt whisky (including the well-known one, Springbank) are made. It is one of two distilleries where every step of the process, from malting the barley to filling the bottles, is done in one place.

Tours were at 10 and 2. I decided to take the morning one, then catch the noon bus back to Southend, play golf, return to Campbeltown on the 4.15 p.m. bus, and then get on the road to the next destination, Carradale, 16 miles to the north.

When I went to the whisky shop in town to buy tickets for the tour I was told it was delayed until 10.30. A bus with 41 tourists was running late. This wasn’t what I expected for the first tour on a Monday morning.

Also signed up for the morning tour was a German named Roger, who had toured Talisker on the Isle of Skye the year before and was heading to Islay the next day to take in three or four more. We waited at the distillery gate for more than half an hour. Finally, a ruddy-faced man named Jim came out and said he’d show us around. The bus wasn’t going to arrive until 11. So instead of having 43 people on the tour, we had two.

As you can probably imagine, making whisky is a complicated process (although the distilling team consists of only six people). It starts with soaking barley in water and then spreading several tons of it on the floor, where it is turned six times a day as it starts to germinate, turning the starch into sugar.

Germination is stopped by drying it. For two of its three types of whisky, the distillery does this with heat that also contains smoke from burning peat. One type gets six hours of smoke exposure, the other 48. That’s one of the reason they taste different.

There are many more steps leading to distillation, which is done twice. (Actually a fraction of the run is distilled a third time and added to the final product, which is why Springbank is marketed as “distilled two and one-half times”).

At one point the liquor is clear “spirit,” more than 70 percent alcohol. Very powerful, but not tasteless.

Then it goes into oak barrels that have been previously used in bourbon making, or had once held Spanish sherry for six years. The spirit sits in the barrel, unturned and untouched, for at least 10 years. It gets its color and some of its flavor from the essences extracted from the wood.

I missed the vatting and bottling steps because I had to catch the bus. There were six people on it. I struck up a conversation with one of them, a man named Mike Healey.

He had just retired from the Glasgow School of Art. The hotel I’d stayed in in Glasgow was right next to the school, so I knew about it. He taught graphic art and lived with his wife in Southend, where she’d been a primary school teacher. He’d been a visiting professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art for a year in the early 1980s.

He’d won a scholastic prize when he’d graduated from the Glasgow School of Art that paid for a year of travel in the United States to meet artists. He crossed the country five times on buses. One of the artists he visited was Norman Rockwell, who invited him to stay at his house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for a week.

“Rockwell was a modest man and a perfect gentleman. He lived in a rented house.”

Rockwell was painting a picture of the Liberty Bell with a birthday ribbon tied around it, in preparation for the Bicentennial. His studio was large and had all sorts of props and costumes in it.

“He’d bring whole groups of people in from the town to pose for his pictures. It was like a theatrical stage really. A photographer would take pictures and he would do a lot of the work from pictures.”

When Mike went to the United States he assumed he would end up living there. He enjoyed his time, although it was a lonely year. When he left he knew he wasn’t going to live in the United States.

“It’s really about six countries, isn’t it?”

I should have asked Mike to play golf (he said he did occasionally), but unfortunately that didn’t occur to me until I was here:

I also spent a fair amount of time here:

The views were spectacular, the greens small, the wind nearly constant. There are no electric carts. There were hardly any players.

The big island in the distance, Sanda, was once owned by Jack Bruce, the bass guitarist for Cream.

I only played 15 holes (although I played two balls on some) because I had to catch the bus back to Campbeltown. I went out with eight balls and turned in the bag with one left. So I might not have made it around 18 holes even if I’d had the time. It was lots of fun.

Before I left Campbeltown I stopped by the garden for the town museum to see the statue of Linda McCartney, who died in 1998. She, her husband and their children spent a lot of time in Kintyre and were much loved (and protected) by the locals.

I finally got on the road. There were a lot of hills as I cycled the road up the east coast of the peninsula. It was a sunny day and felt like about 4 o’clock when I reached Carradale, although it was actually after 8.

I didn’t get underway until after noon the next day, as I needed the hotel’s wifi and it took a lot of time to upload pictures. It was again sunny and beautiful when I hit the road. I went through a tiny burg with an interesting name. Let’s hope that at least one of these signs is wrong.

I made an unexpected detour on the way to visit the ruins of Skipness Castle, which was built in the 1200s and still had some local workers occupying a few rooms in the late 1800s.

It faces a body of water called Kilbrannan Sound, with the Isle of Arran (Scotland’s, not Ireland’s) in the distance. Between the ruin and the water were fields with sheep and horses grazing. At one corner was a seasonal seafood restaurant with picnic tables outside. I got lunch there and watched three border collies watching and following two orphaned lambs in fenced pen.

The castle was, well, just about everything one could hope for in the ruined-castle department. You could walk all the way up to the parapet and stroll around like the ghost of Hamlet’s father.

There walls were feet thick with little windows.

This is a view out the front door.

It’s hard to know whether this shooting port has intentional religious meaning as well.

I rode back to the junction where I was going to ride northwest over the hills to the western shore of Kintyre, there being no road all the way up the east to Tarbert, where the ferry terminal is. I had left my pack at the junction with this delightful couple, Ali and Steve Ashford.

The are musicians who had moved up from England and bought a stone church that had been built in the 1750s and had closed in the 1970s. There are a fair number of desanctified churches in Scotland for sale; they are the fourth owners of this one. Previous owners hadn’t gotten far in renovations because the owner of the estate wouldn’t give them access to water. He thought he should control the church even though he didn’t own it, Ali said.

The estate has been sold and the new grandee is a Swede. He gave the couple access to a stream for water. They are renovating it themselves, living in a camper on the grounds with their Mexican hairless dog. The work is complicated as well as hard because the building is on a historical register that limits exterior changes, but all sorts of modern code requirements must still be followed. Ali and Steve think they’ll be able to move in in about a year. Stupidly, I didn’t take a picture of the outside.

I hope to see it, and them, again sometime.

I had 10 miles to go to get to Tarbert. (I’d gone 19). The ferry to Portavadie, where Deborah and Paul were going to meet me, left Tarbert at quarter past the hour.

I left the old church at 5.15 and rode four miles over the hump. I got to the coast road with six miles to go and 30 minutes until the 6.15 ferry left. I thought I could make it, but if I didn’t that was fine, as I’d told Deborah and Paul I would probably be on the last one, at 7.15.

I pedaled along and got to Tarbert and a dock with a ferry, but no signs of any people except for a forklift operator, at 6.04. He told me the ferry that was working was a half-mile on. I got there at 6.09 and pulled in behind three cars. The boat was already lowering its ramp.

My phone had about 5 percent battery life left. I called my friends a couple of times at their house–no answer. I e-mailed Deborah. (Paul doesn’t carry a cell phone). I resisted taking a picture of a salmon fish farm (with the poor caged fish going around in circles and jumping out of the water) that we passed in the crossing. I wanted to save what little juice was left to call when I got to the other shore.

As the boat approached land the landing, I saw two people standing on the road. They looked familiar.

I walked off and said, “How did you know I was on this boat? I’ve been calling and texting you?”

“Did you get the e-mail I sent last night?” Deborah said.

“No.” (I don’t know what happened to it; maybe it went to the iCloud address).

“We were reading the summer schedule, which hasn’t started yet. This is the last boat.”

Recent Comments