So here’s a little about the Moray Coast, much of it thanks to the book, “Portrait of The Moray Firth” (1977) by Cuthbert Graham, former weekend editor of The Press and Journal, a newspaper in Inverness.

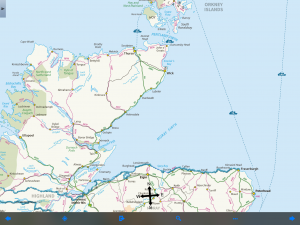

The Moray Firth is an isosceles triangle lying on one of its equal sides. It’s roughly 100 miles from Inverness to Fraserburgh (where the land makes a 90-degree turn south), and 100 miles along the southwest-to-northeast diagonal whose apex is Inverness. The other side, which connects the headlands in Caithness and Aberdeenshire, is about 75 miles long.

Moray Firth is a drowned river system. The upper side of the triangle–which is to say, the northern shore of the firth–likes along a geological fault line that includes Loch Ness, the Caledonian Canal and various other lochs down to the Firth of Lorne on the Atlantic Coast.

Creating Loch Ness’s fabled depth, the rift is like a deep saber slash running diagonally across the Highlands. In the Moray Firth, it is evident as a trench, known locally as “the Trink,” a half-mile wide and15 fathoms below the rest of the sea bed.

For reasons that are not obvious to me, the coast gets less rain that other parts of the Highlands and points west. Nairn, which is the next town of any size east of Inverness, gets about 25 inches of rain a year, half that of Stornoway in the Outer Hebrides.

Neolithic people built many tombs, some of which remain as stone circles or ring cairns, the ground-level outlines of the burial chambers. However, they are easier to find on the map than on the landscape.

After the start of the Common Era, the Picts were carving stones with pictographic inscriptions, and later, after their conversion, with Christian and Celtic crosses. They left no written language, and the meaning of many of their stones can only be guessed. One of the better known and later ones, Sueno’s Stone, which I walked by, is thought to depict the course of a conquest, culminating in the beheading of the vanquished.

By 875 the Norse had conquered the land north of the northern side of the firth, which remained a Norse province for 350 years. The southern side of the firth was a buffer between the Scandinavian invaders and the Scottish kingdom to the south. Its rulers sometimes claimed, or usurped, the Scottish throne.

The most famous was Macbeth, who in 1040 killed the Scottish King Duncan. Duncan had killed the brother of Macbeth’s wife, Gruoch (whose name Shakespeare wisely chose not to use), in order to consolidate power. Duncan died not in Inverness Castle, but at a blacksmith shop near Elgin, inland from the mid-Coast. Macbeth was subsequently killed, in 1057, by Malcolm Canmore, who later unified Scotland.

This is Macbethland. I’m walking near Cawdor and through Macduff. I’m spending the night at a B&B in Forres, the village that is the site of the scene in Act 1 in which a wounded sergeant reports Macbeth’s battlefield heroism to King Duncan. Birnam Wood and Dunsinane Hill, however, are farther away.

Various wars and battles, both religious and secular, occurred along the Moray Coast over the centuries. The 1746 Battle of Culloden, the last great battle fought on British soil, ended the Jacobite Rising and began the legal suppression of the clan system.

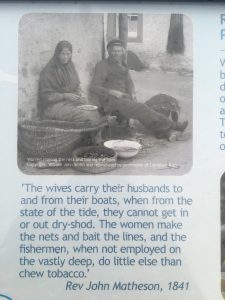

The coast received people during the Highland Clearances in the late 1700s when subsistence farmers were replaced with sheep on huge, often absentee-owned, estates. At various times the area’s industries included flax spinning, herring and salmon fishing, whisky distilling, and farming. In the 20th century, there were a number of big military installations, most now closed. Golf-based tourism appears to be important today.

In its western and central segments the Moray Coast has sand beaches that are a quarter-mile from wrack line to water at low tide. Yesterday, as I walked from Findhorn to Burghead, I turned around and saw a gigantic anvil-based cloud illuminated by the late afternoon sun. (The sun which wouldn’t set for another four hours).

About the middle of the coast cliffs start to appear, and they eventually dominate the eastern end of the coast.

National Geographic Traveler magazine in 2010 asked a panel of 340 experts to rate coastal destinations for “authenticity and stewardship.” The Moray Coast was 11 out or 99 (tied with Italy’s Cinque Terre).

It’s a placed that moved the aforementioned Mr. Graham to write: “Nothing in fact can be so exhilarating as to climb up over the Spartan uplands of Aberdeenshire or Banffshire till one reaches the windswept plateau overlooking the coiffed coast . . . where a breeze from the north-west is ruffling the manes of the waves’ white horses while, on a really good day, the thin blue line of the Sutherland hills is faintly visible on the water’s far horizon.”

I can’t attest to all of that. But it’s pretty nice so far.

Recent Comments