After crossing Loch Ness I had a long climb up an old asphalt road that announced at the bottom it was not suitable for caravans or heavy loads. This took me out in to some landscape that I can’t recall at the moment; probably farms. Eventually, though, in the middle of the afternoon I got to a sign one wouldn’t expect to see in the middle of nowhere: artist’s studio.

Equally curious as wanting an excuse to rest, I turned into the driveway, opened and closed the gate and proceeded to a green rectangular building that had an “Open” sign pointing to a door that was, in fact, partly open. When I looked inside, however, there was no one there. Another sign said that if the artist is not in the studio, knock at the house, which was a white building a few feet to the left.

This I did, and soon enough a woman with braids came out and asked if I wanted to see the studio. She craned her head in a diplomatic way to see if there was a car in the driveway, which there wasn’t. I explained that I was walking and that, frankly, I was looking for a reason to take a break.

And so began my two-hour visit with Ros Rowell, an example of why it’s always better to stop than pass by.

Ros is a year younger than me and an example of someone who did what I and some of my friends sometimes fantasized about in college–going back to the land, or as it might be called now, going off the grid.

She grew up in northeast England–County Durham, North Yorkshire–which she said is a place more Nordic than English. And, in fact, she looked vaguely Nordic, although maybe that was the braids talking. She’d moved a lot when she was young–I found out nothing about her childhood–and eventually went to the University of Edinburgh, where she got a “First”–honors of some sort–in zoology. She went on to earn a doctorate in parasitology, doing research in malaria. The project she was working on was funded by the U.S. military, which had an interest in malaria because of the Vietnam War. (It still does, for other reasons).

“I actually came to feel it was unethical,” she said. “It was the era of Bob Dylan. I wasn’t sure I wanted to get involved in it.”

Ros is a free-associative talker, driven by the desire to tell more and make more connections. This despite the fact that she said several times that her health has “never been brilliant” and that she’s now slowing down. In truth, I was keeping her from preparing for a show at a new gallery and the arrival of a group of child art students in the next few days (although she did continue to work as we talked).

Ros had the opportunity to do further malaria research in Gambia, but turned it down. She had met a geology student named Alan Hutchinson. They lived together in Edinburgh and had “an allotment”–a piece of ground they could grow vegetables on–five miles from town. They used to “cycle tea bags and peelings up to it for compost.”

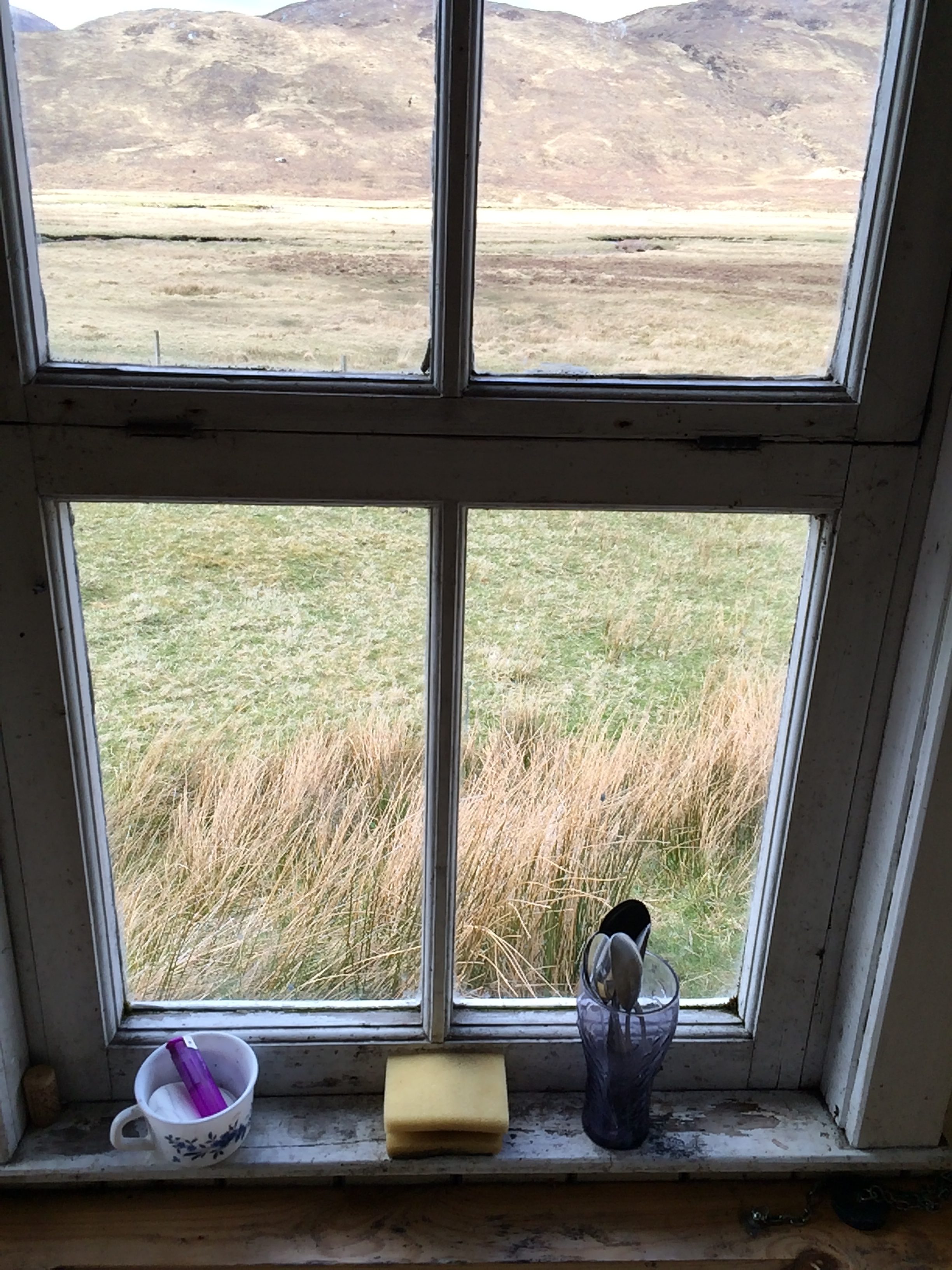

They finally decided to go whole hog (and sheep and goat, as well). They bought a croft with a several acres in 1983 for 14,000 pounds. It was called “Edinuanagan” (although the spelling is different on the Ordnance Survey map I’m using). It translates to “slope of the lambkins.” The house had two rooms. When it was built is unknown, but long ago. At least three families have shown up at the door wanting to see the place where one of their ancestors had lived.

It was originally a “black cottage,” with no chimney and the smoke finding its way through the thatch roof. The exterior stone walls are two to three feet thick. It sits on an incline, and in the first year water sometimes ran over the floor.

Alan worked on the oil rigs in the North Sea. They raised animals and vegetables and worked on the house. Occasionally, Alan would take bags of goats milk to Inverness to sell. The times were difficult.

“You can’t live off cabbages and potatoes and onions indefinitely. As my mother said, ‘If it worked, everybody would be doing it.’ ”

They stayed, however.

Ros had gotten her teaching credential, and she taught primary school in Inverness. She rode a motorbike or the bus to work. In 1985, she had a child, Callum. Four years later, they had another, a girl named Mairi. They put up a building and ran a hostel for a while. They finally got a car. Before that, they’d shop in Inverness by biking in the 15 miles and filling a backpack. Or sometimes getting the man at the grocery to fill a box and put it on the bus.

“It is more difficult to run things with two children when you don’t have a car,” she said.

Here they are with the two children. On the right is a picture of the croft as they bought it.

Her daughter became ill, requiring trips to Glasgow. Ros stopped teaching school. Alan by then was off the oil rigs, working as a forester. They added on rooms to the croft. Their land became a small agricultural experiment station.

“You can probably find this pattern all over America. Have you found it?”

“Of course. Vermont is full of it,” I said.

“It seems like just a story now,” Ros said. “It’s a long time ago.”

Ros began painting in 1990. She is essentially self-taught. She paints in watercolors and in fauvist oils. Her watercolors of Loch Ness and the glens–valleys–are especially popular. Art, she said, is partly a way of coping with trouble and loss–illness, the drowning of a neighbor’s son, the death of an 11-year-old friend of her children who was hit by a car coming home from school.

She gave me two cups of tea, and biscuits, while she drilled the backs of picture frames and tied cord on for hanging.

Her son, Callum, studied “human-computer interaction” at the University of Edinburgh and has a good job. He has Gaelicized his last name to Macuisdean, which means “son of Hugh” (which Ros said is what Hutchinson means). He is engaged to be married to a woman who grew up in Greece, the daughter of a German father and English mother who had gone back to the land there. She said her parents “have spent their lives building the ideal retirement villa”–which would describe Ros and Alan’s holding perfectly. She told Ros: “I knew Callum was wonderful, but what clinched it was coming home and meeting the parents.”

Ros added: “They’re having a Quaker-pagan wedding.”

Mairi is well now, and is an artist. She is engaged to marry a Californian, who is studying in Edinburgh.

Before I Ieft to slog on down the road, Ros gave me a tour of the place. It includes a greenhouse; a warm, plastic-enclosed “tunnel” (she called it) where all sorts of things grow, including figs.

They have an ancient Massey-Ferguson tractor and an implement that digs potatoes.

On a long, sloping outdoor garden they grow potatoes and lots of other things: black, white and red currants; pink gooseberries, Saskatoon berries, sloe, raspberries, strawberries, and grapes (from which they make wine).

And she makes art.

She believes in Scotland, although “nationalism” is a concept that doesn’t appeal to her much.

“I’m a socialist. I’m a northerner. I believe in the commonweal.”

Recent Comments