It’s been a while. It’s amazing how time runs together even when you’re only talking about three days. Part of the reason is that this is what’s been on my mind.

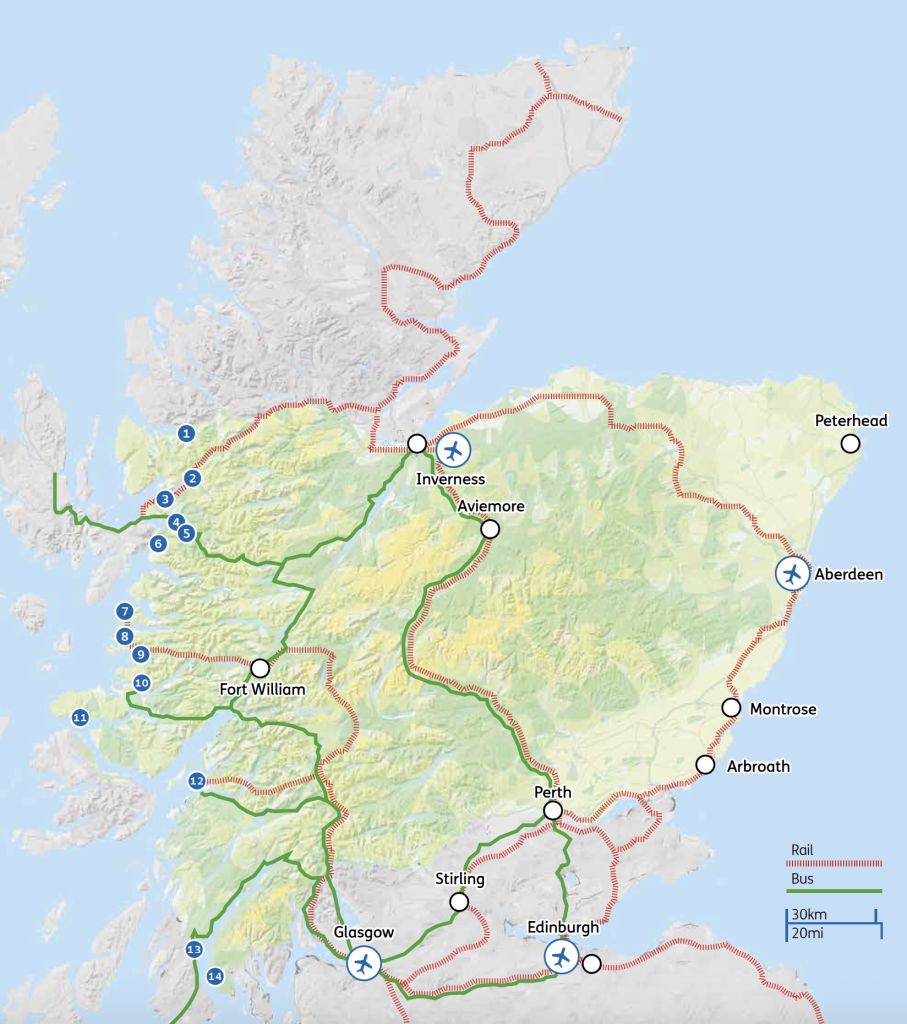

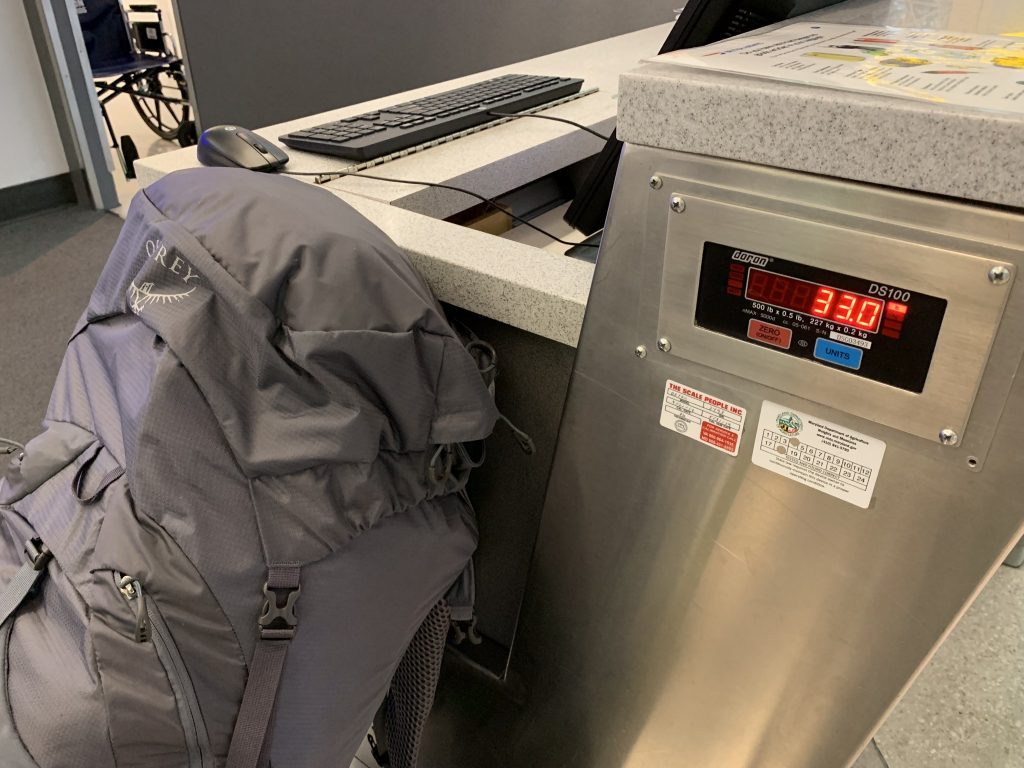

I won’t belabor the point, especially given the subject. But let me just say that pain in the feet when you’re supposed to walk 241 miles with 38 pounds on your back is a concern.

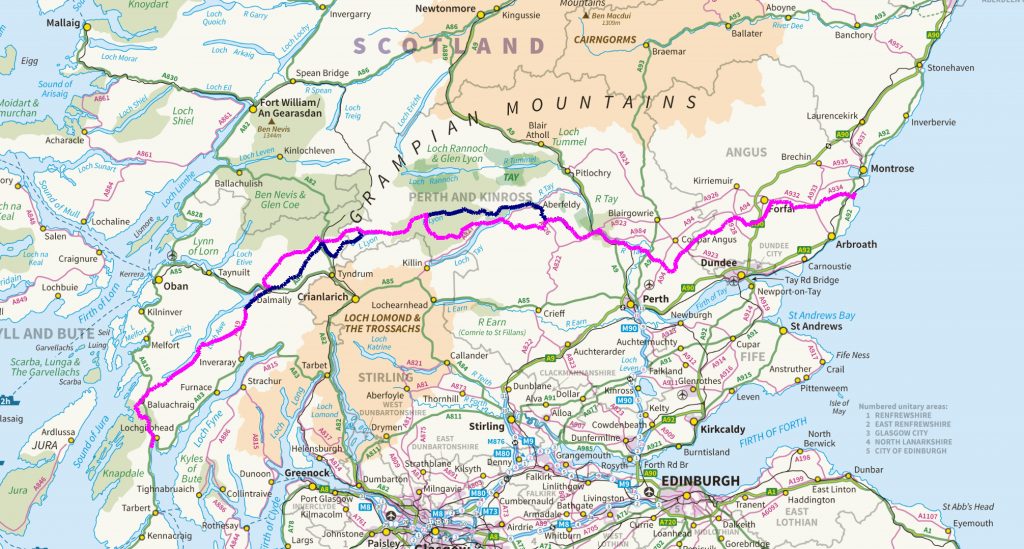

When I left Kilmartin I was on roads for most of the day, the exception being a few stretches of what the UK topographic maps (called Ordnance Survey maps) call an “old military road.” In most cases, they are roads created by the English army when it suppressed the Jacobite Rising for Scottish independence in the mid-18th Century.

(This, by the way, is not just a historical irrelevancy. Scotland has a history of being allied with France ((read: Europe)) against English domination. It helps explain why Scotland opposed Brexit.)

I was in enough pain that I stopped a mile and a half before my intended destination at an ancient boat ramp on a loch that is the site of the first photograph of this post. I looked around, not very hard, for someone to whom I could ask permission. Finding no one, I relied on “The Scottish Right of Public Access,” which allows people to walk across private land, and camp on it too (away from animals, habitations, military reservations, airports, and Queen Elizabeth’s estate Balmoral). It turned out to be far better than where I would have been if I’d gone the distance.

(I should say at this point that, four days in, I have not met a single other walker on The Great Outdoors Challenge. Three miles before the aforementioned stopping point I saw a man setting up a Hilleberg tent—the most popular shelter among Challengers—on a flat piece of ground next to the loch the road was skirting. I don’t know if he was a Challenger, although I suspect he was. I would have liked the company, but it was too early, for me at least, to stop.)

The next morning, the owner, a man named Richard—he didn’t offer his last name—appeared. I told him who I was and what I was doing and he was non-plussed by my pitching a tent near his derelict boats.

This is the Scottish way.

We chatted about the weather and I asked him about sheep; his is a working farm. He mentioned that the reason one sees so much wool on the ground this time of year—frankly, it reminds me of cotton on the road during harvest time in the Mississippi Delta—is that wool grows year-round, but when spring comes, with high-protein new grass for feed, the fibers become thicker and the fragile winter growth drops off. This is why you find random gouts of wool out in the hills.

I thanked him and headed down the road. The macadam—and, by the way, “macadam” is named after the Scottish inventor of road asphalt—was hard on the feet.

This was a one-lane road with frequent “passing place” pullouts. It was Sunday. Not many cars passed me. I heard a quiet one behind me and figured it was a Prius. It turned out to be four bicyclists. By the third mini-peloton that came by I had my phone out.

I trudged on. I forget the details.

My right foot is turned outward slightly and I have blood under four nails. An attentive fourth-year medical student would detect “antalgic gait.” But like I said, I won’t belabor things.

I was scheduled to stay in a B&B that night, and I did, finally reach it. It is in the village of Cladich, which has nothing other than two B&Bs. “Cladich” means beach in Gaelic, and refers to a sandy strand on the loch above the village that has been extirpated by a hydroelectric scheme (as they call them here).

The proprietress, Sarah, kindly washed my clothes.

I was glad to be there.

Recent Comments