I took a cab from my hotel in Cumnock to the entrance road of Priesthill Farm, two miles north of the village of Muirkirk. It was a 15-minute, 40-pound trip. This is Ayrshire, 40 miles south of Glasgow—the Scottish Lowlands.

The farm fields are bright green with new growth, the moorland still mostly brown. Wandering across both are sheep—ewes with lambs a few weeks old.

John Brown was “of Priesthill” in the historical accounts of his life and death. He had a few animals (more likely cattle than sheep) and planted a small amount of ground, but almost certainly didn’t own land. Priesthill was probably a hamlet of a few houses. There’s a house with barns there now, but nobody appears to be living in it.

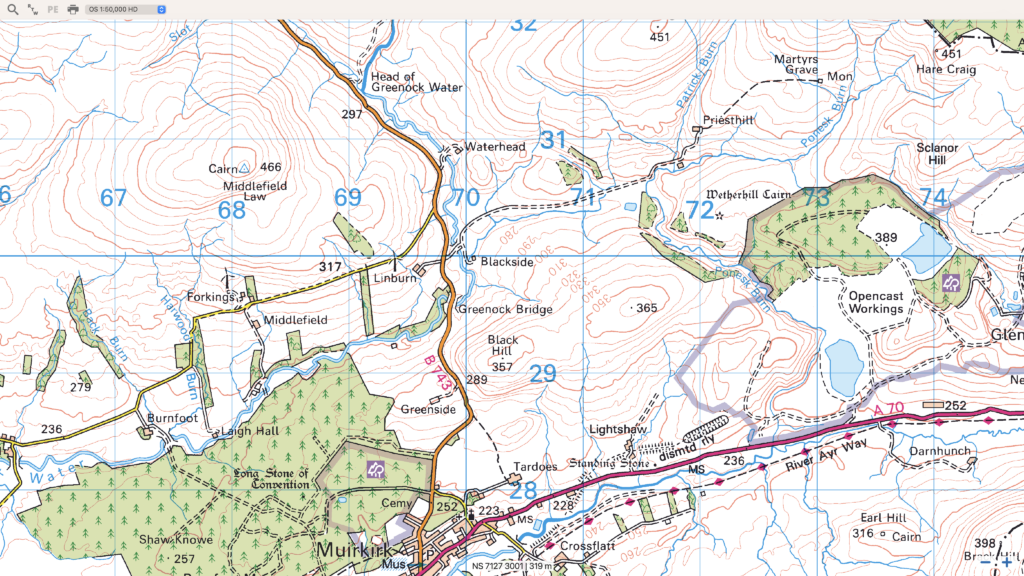

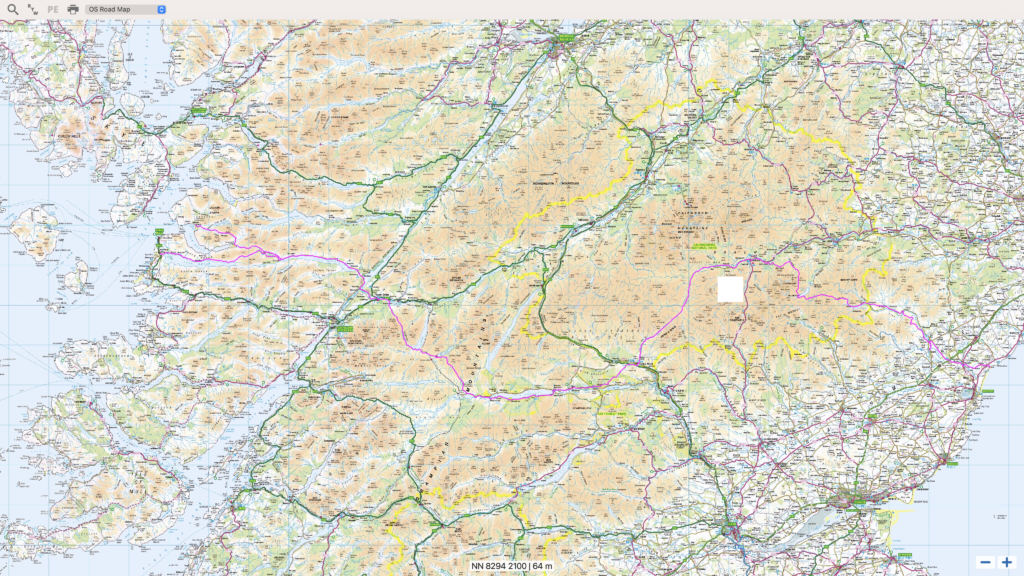

This is the part of the Ordnance Survey map–the U.K.’s topographic service–showing Priesthill in the right upper quadrant, and beyond at the end of a trail the “Martyrs Grave.”

When you stand in a particular place, particularity comes to mind. Who was this John Brown?

Not a lot is known. He was born in 1626 and wanted to become a preacher, but a speech impediment prevented that. He became a “pack-horse carrier,” ferrying goods to market for people, and bringing things back for them–a FedEx driver in a place with no roads. His religious devotion gave him a name, “the Christian Carrier.” His first wife died. He almost certainly spoke Scots, a variant of Middle English. (Gaelic was restricted to northern Scotland and the islands off the west coast.)

He was married to his second wife by a famous Presbyterian preacher and seer, Alexander Peden, who ruined the wedding festivities by telling the bride: “You have got a good husband . . . keep linen for a winding sheet beside you; for a day when you least expect it, thy Master will take him from thee.”

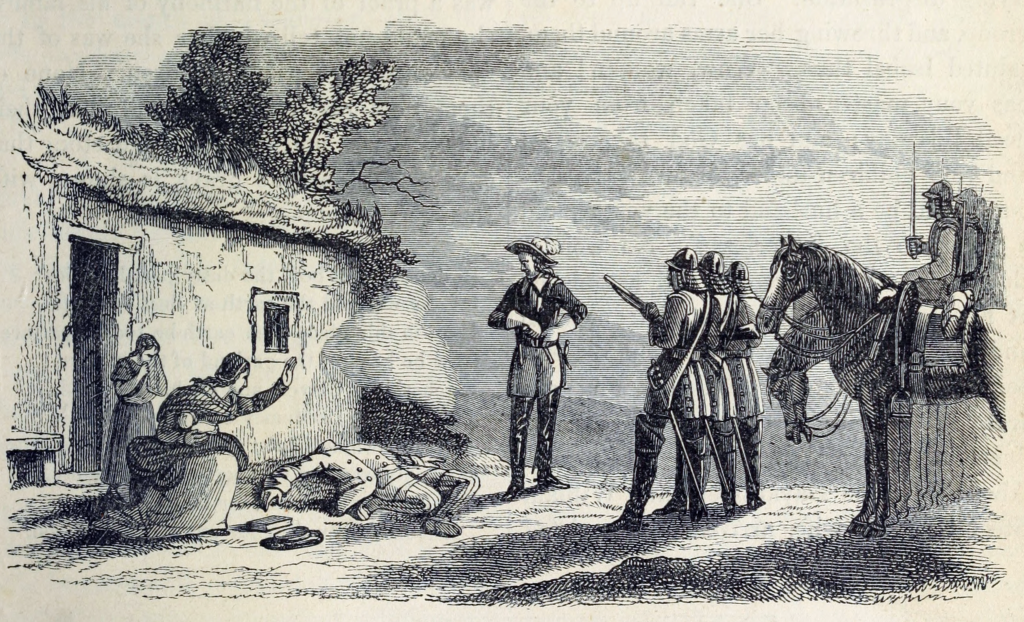

That day was May 1,1685, when John Graham of Claverhouse and his mounted troops caught John Brown cutting peat. They brought him to his house, where his seven-year-old daughter told her mother what had happened. When Brown refused to agree to attend Anglican services, he “kneeled down and prayed loud and fervently, in words that appalled the soldiers,” the author of the 322-page genealogy of his descendants wrote.

Graham ordered his troops to shoot him, but they refused, so he drew a pistol and did the deed himself. A man of curiosity, he then asked Brown’s wife, Isabel, what she thought.

“I always thought much of him, but now far more than ever,” she’s said to have said.

Graham didn’t like the answer. ” ‘Twere but justice to lay thee beside him.”

“If permitted, you would do so,” Isabel observed. “But how will you answer for this morning’s work?” He mounted and rode off with his troops.

If even half of that is true–or a quarter–it’s still a hell of a story.

On my day at his grave, the sky was overcast and misting enough that water droplets eventually formed on my eyeglasses. It was chilly, too, but the walk was mostly uphill, so I got warm enough to unzip my jacket halfway.

I expected to find the monument and grave on high ground, but it wasn’t. It was across a ravine with a step-over stream running down it, and halfway up the other side. It appeared out of the mist like a navigational beacon on an ocean of grass.

Up close, it looked like a pale and startled corpse had sat up in its coffin to look around.

One account says that Brown was buried where he was shot. That means he would have been buried outside his front door, which seems unlikely. The grave also didn’t seem like a good house site; I suspect the family lived on the high ground where uphill path finally leveled off.

Brown’s grave is inside a stone enclosure. (The size and cut of the blocks testify to what people thought of him.) A stone slab lies on the ground.

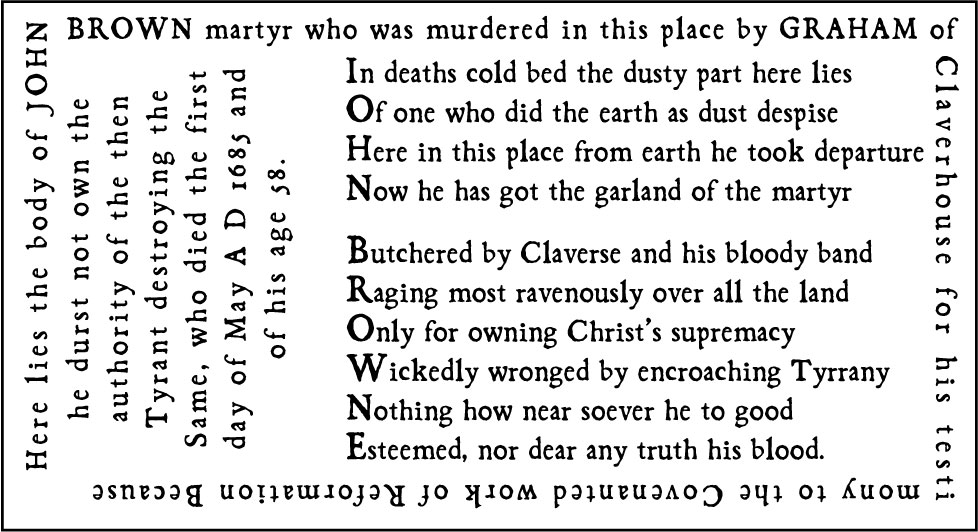

Its inscription is unreadable, but fortunately someone recorded it in a drawing. It features an acrostic that reads from top to bottom “IOHN BROWNE,” or JOHN BROWNE in modern orthography. (I don’t know why there is a variant spelling of the last name, which is spelled correctly elsewhere on the stone.)

I can’t say I understand the acrostic, but the inscription around it is comprehensible.

Here lies the body of JOHN BROWN martyr who was murdered in this place by GRAHAM of Claverhouse for his testimony to the Covenanted work of Reformation Because he durst not own the authority of the then Tyrant destroying the Same, who died the first day of May A D 1685 and of his age 58.

That’s 339 years and three days ago.

The monument was added later (in 1826, to be exact). Time, water, and lichen have rendered it nearly indecipherable, too.

At the corners of the stone enclosure are the remains of hardware that might have been grommets for a covering or anchors for a fence. One piece has rusted so that it looks like a miniature lion threatening anyone who’d even consider disturbing Brown’s bones.

This is his spirit’s view each day. (I took a picture of the two of us.)

And then it was time to go.

I walked back to the road, never to return, as his wife and children had. Two of them eventually came to America. The wisdom of crowds being what it is, they probably walked down this very path.

John Brown laid down his life for his religion, an act that’s gotten a bad name in recent decades. (Personally, I think the world could use less of it.) But that’s only part of what he did. He showed courage. He remained calm. He eschewed violence. He died for principles.

A few other people who did those things when circumstances called came to mind.

Nathan Hale, the American patriot hanged by the British at age 21. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, German pastor and anti-Nazi dissident hanged on Hitler’s orders a month before Germany’s defeat. Jean Moulin, a leader of the French Resistance tortured to death by Klaus Barbie in 1943. Arrigo Paladini, an Italian partisan who, like Moulin, revealed nothing under torture, and escaped execution only because the truck taking him to the killing grounds wouldn’t start on the day the Allies entered Rome (June 4, 1944).

Almost nobody has heard of John Brown, the “Christian Carrier,” Covenanter, martyr, but he’s in their company.

I’m sure his shade couldn’t care less. However, I do. Who doesn’t thrill at learning there’s a hero in the family? Who doesn’t hope that, somehow, long-ago courage breeds true to the present?

There’s little chance of that. In fact, there’s a 37-percent chance I share no genes at all with John Brown, my seventh-great grandfather, or his brave wife. Statistically, I should inherit 0.2 percent of my genes from each of them. But linkage events during meiosis can lead to unequal segregation of genes, so my inheritance may be 0.0 percent.

If that’s the case, John and Isabel Brown’s contribution to me is homeopathic, so dilute that only the vibration in the solvent–the “resonance,” as homeopaths call it–remains.

The funny thing is: that’s enough.

I stand on ground calcium-rich from his dissolved bones and listen to his words, the demand of the officer, the pistol shot, the crying of his wife and children, the retreating hoofbeats, in silence.

I’m grateful to be called one of his descendants. That’s plenty.

Recent Comments