We spent our last day in Sardinia sightseeing, not paddling. The main destination was an archaeological site in an area called Arzachena once inhabited by the Nuragi people.

I had never heard of the Nuragic Civilization. As described by our guide, the chief archaeologist of the site, the Nuragi inhabited a pre-Christian island Eden, a Thousand Year Reich of peace and prosperity in the Western Mediterranean, a model of egalitarianism and possibly even democracy a world apart from the war and autocracy to the east. (See the Old Testament for the latter.)

I suspect much of that is exaggeration and Sardinian chauvinism. The guide, Mauro, was intensely proud of what his region was and is. But given his credentials, some of it must be true.

The Nuragic Civilization existed from 1700 to 500 BCE, beginning in the Bronze Age and ending in the Iron Age. It’s distinctive architectural feature is the nuraghe, a conical building with a small flat, or sometimes bluntly rounded, top. It is made of native granite. There is no mortar. The stone is laid in overlapping courses, which distributes the weight laterally as well as downward.

From the inside the structure tapers upward in a classic beehive shape. It is finished with a capstone that is not—as with an arch’s keystone—essential for the building’s stability. Some nuraghes had two storeys—one beehive super on top of another.

The purpose of a nuraghe wasn’t clear from the tour, or at least not to me. Mauro went to lengths to say they weren’t castles. There wasn’t enough room in them to house the village’s people, and there aren’t obvious features for armaments.

At least part of their purpose was to mark settlements, link communities visibly, a provide a sense of cultural unity.

A pamphlet published in 2003 (before much of the recent excavation) and sold at the ticket shop said that while their precise use isn’t clear, archaeologists agree they “were buildings of a civil and military nature, destined in particular for the control and defence of the land and the resources on it.”

The people who built them were indigenous Sardinians, or at least not known to be immigrants. (Except for East Africans, we’re all immigrants). DNA from Nuragic skeletons suggests modern Sardinians descended from them, our guide said.

About 8,000 nuraghes survive, although few are complete. Many are in complexes with three or four others. (The largest, found only four years ago, has 15 towers). In many, a large central tower is attached to smaller satellite ones, like the ones at the corners of forts separated by walls, except that here there are no walls.

Nuraghes exist only in Sardinia (mostly in the north) and in southern Corsica. They bear some resemblance to smaller round-topped, dry-stone buildings in France (bories), and in Scotland and Ireland.

Mauro said there are three reasons the structures are still standing. First, Sardinia has been largely peaceful for the last 4,000 years. Second, the island isn’t earthquake-prone. Third, the prevailing wind from Corsica has buried many of the buildings in fine sand, rendering them protected and invisible.

The one we visited was covered except for its top until 1989. An open hole down into the structure was thought to be a place where prisoners might be thrown. As a consequence the spot, popular for picnics, was called “la Prisgiona.”

The top storey of the nuraghe was dismantled in 1820 when the Savoy family, from the mainland, took control of the island. Under its administration, people were instructed to delineate farm plots; before that the land was held communally. The inhabitants cannibalized the towers for stones for walls and boundary markers.

The excavation, which had just ended for the season, had slowly uncovered the tower. A bunch of surrounding structures, nearly all round, were thought to have been workshops or mercantile establishments. A well 30-feet deep contained 16 vases, 2 copper rings and 2 bronze rings—apparently left there as some kind of offering. About 500 to 800 people lived in the settlement, occupying farther flung dwellings. The footprints of some have been found.

One of the more interesting structures, common to nearly all settlements, was a “meeting house.” It had a bench circumscribing the inside wall, and a built-in stone table in the middle. Found in the house here were 12 cups, a vase and a serving spoon. Mauro said archaeologists believe the meeting houses were places of decision-making, and that the lack of preferred seating or a throne suggests a political structure built on consensus and equality.

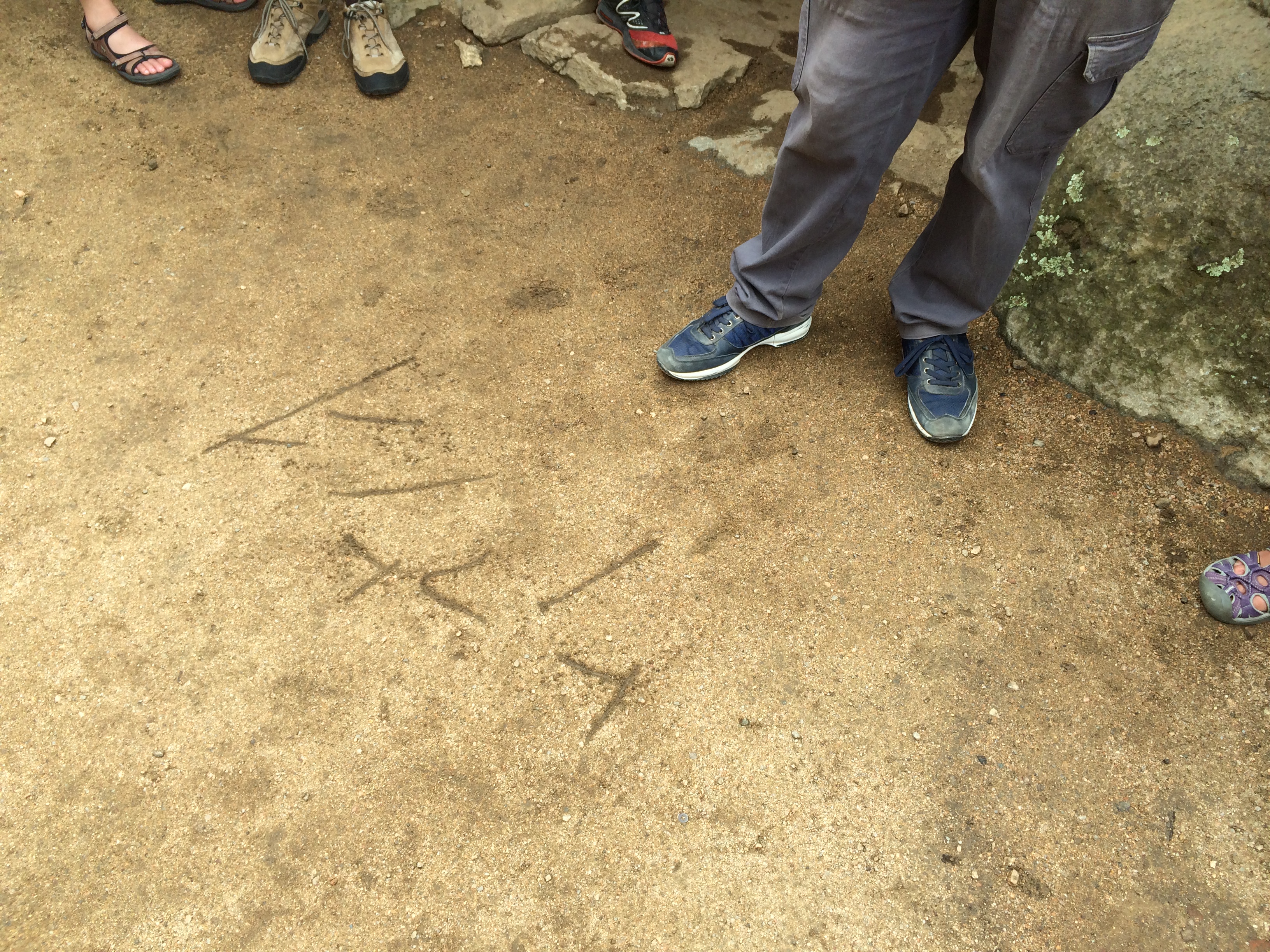

The Nuragi apparently had no written language. Only a few words survive. One of them is “Sardinia.” Another place name dating from their time is Olbia (where our overnight ferry came and went from), which means “city of the loving God” in proto-Hebrew. There are a few other words that have similar origins. At one point Mauro wrote a Hebrew word in the dirt and pronounced it.

He said there was evidence that Nuragic Civilization spread to other places, too. In 2006, a proto-Sardinian structure and artifacts were found 12 miles south of Haifa, Israel.

The Carthaginians, Phoenicians and Romans eventually brought war to Sardinia, ending the lotus-eating era of the Nuragis. What exactly happened to them isn’t known.

Recent Comments